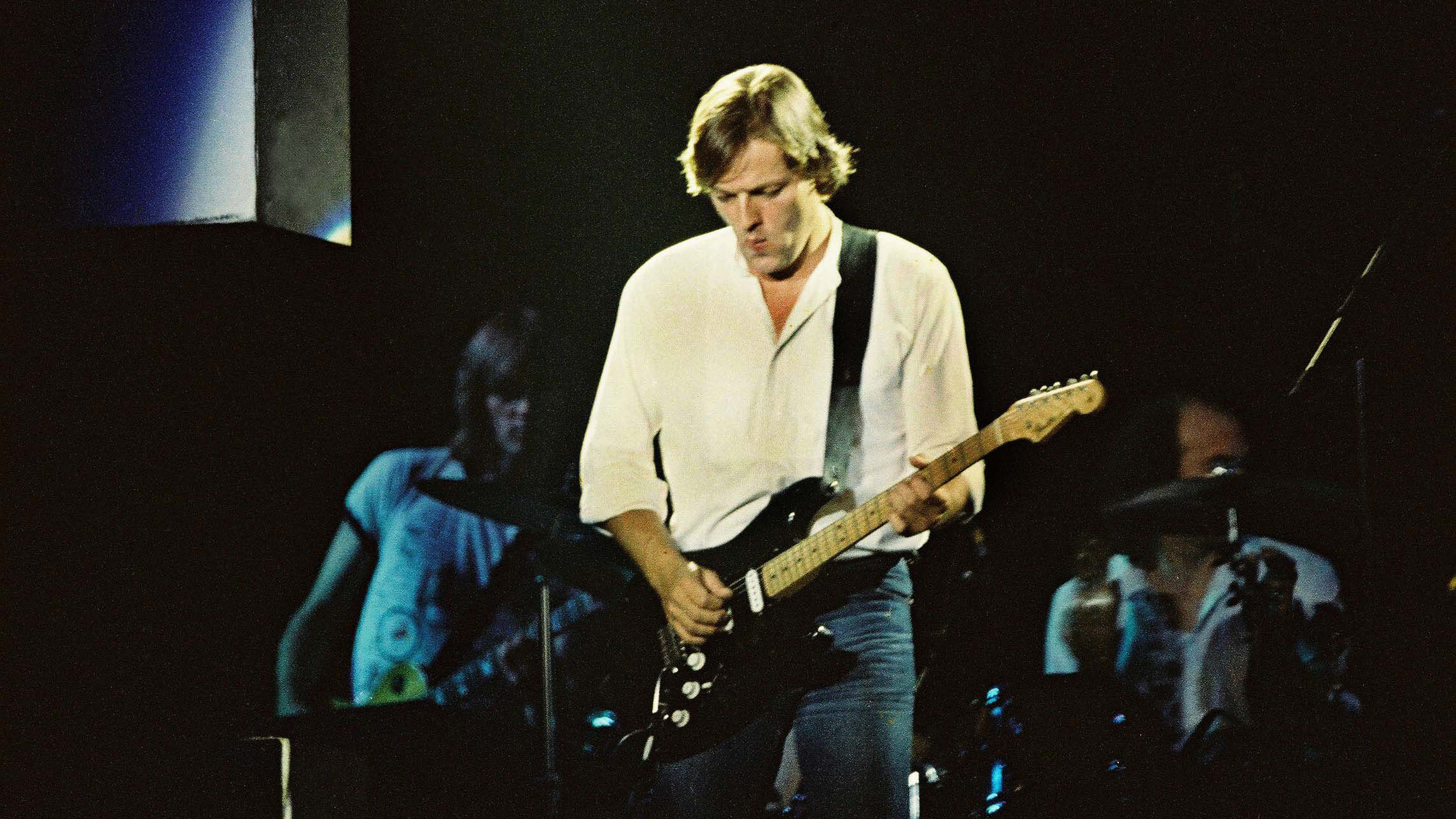

“Man, this is a hit!”: Roger Waters’ vision, David Gilmour’s classic solo and a disco groove - the magic combination in Pink Floyd’s freak Christmas No 1

“It wasn’t my idea to do disco music," Gilmour said

It was on this day (30 November) in 1979 that the least festive Christmas number one of all time was released.

No sleigh bells. No references to Santa, reindeer, presents, mistletoe or the baby Jesus.

Instead, this Yuletide hit was an anti-authority protest song set to a disco beat. A track lifted from a rock-opera concept album themed on war and death, paranoia and betrayal, fame and isolation.

And while this song did feature a children’s choir, these kids weren’t singing: “I wish it could be Christmas every day!” They were sneering: “We don’t need no education! We don’t need no thought control!”

It was a Christmas number one that was utterly devoid of festive cheer: Another Brick In The Wall Part 2 by Pink Floyd. And it featured one of David Gilmour’s most brilliant and inventive guitar solos.

At this stage of Floyd’s career, bassist and lead vocalist Roger Waters was very much in the driving seat. Not only did Waters devise the concept for the concept album The Wall, he wrote every song alone except for three tracks co-written with Gilmour and one co-written with producer Bob Ezrin.

But if The Wall was Waters’ baby, he acknowledged Ezrin’s role in shaping Another Brick In The Wall Part 2 into a single. “It was great,” Waters said. “Exactly what expected from a collaborator.”

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

It was Ezrin who suggested that they try a disco beat. “I’d just done a session in New York,” he said, “and Nile Rodgers and Bernard Edwards [from Chic] were in the next studio. I heard this drum beat and went, 'Wow, would that ever work great with rock ‘n’ roll!’ When I got to England a few months later and I started listening to Another Brick…, that beat kept playing through my head.”

Disco music was entirely alien to Floyd and to the guitarist in particular. As Gilmour said: “It wasn’t my idea to do disco music, it was Bob’s. He said, ‘Go to a couple of clubs and listen to what's happening with disco music.' So I forced myself out and listened to loud, four-to-the-bar bass drums and stuff and thought, Gawd, awful! Then we went back and tried to turn one of the parts into one of those so it would be catchy.”

As an albums band, Floyd hadn’t had a single out in in the UK for 11 years since Point Me At The Sky in 1968, and Ezrin said he met with resistance as he worked on transforming Another Brick In The Wall Part 2.

“The most important thing I did for the song was insist it be more than just one verse and one chorus long, which it was when Roger wrote it,” Ezrin recalled. “When we played with the disco beat I said, ‘Man, this is a hit! But it’s one minute 20, it’s not going to play. We need two verses and two choruses.’ And they said, ‘Well you’re not bloody getting them. We don’t do singles, so f**k you.’ So I said, ‘OK fine’, and they left. And because of our two machine set-up, while they weren’t around we were able to copy the first verse and chorus, take one of the drum fills, put them in between and extend the chorus.”

Ultimately, Gilmour conceded: “It doesn’t in the end not sound like Pink Floyd.”

And his solo was one of the main reasons why.

For this solo, Gilmour eschewed his Strats for a 1955 Les Paul Gold Top, which sold in 2019 for $447,000, a record for a Les Paul.

He originally recorded the solo direct into the mixing desk but felt the resulting tone needed “more meat.” He persuaded Bob Ezrin to re-amp the solo, sending the recorded take out to a mic’ed up amp. The tone on the record is a blend of the two, an inimitable blend of clean sustain with a hint of grit.

The Another Brick solo is great because it’s so memorable, and Gilmour created that effect intentionally. The opening lick has a distinctive rhythm and ends by bending up to a high D. Four bars later, Gilmour plays an answering phrase using exactly the same rhythm and ends on a D one octave lower. It creates an answer to the question he asked with the opening phrase, and it feels familiar because it repeats the earlier rhythm.

The solo’s second lick is arguably even more important. It’s a compound bend: Gilmour bends the string to one pitch, holds it, and then bends it to a new, higher pitch, creating a melody out of string bends.

In 1979, this was the cutting edge of guitar technique, the first time most listeners had heard anything like it. Gilmour plays variations on that theme twice more, adding more hooks to the solo.

Later on, Gilmour relies on some of the same tricks that made the Comfortably Numb solo so effective, although they sound quite dissimilar thanks to the different tones and musical contexts.

There are aggressive pentatonic double stops, and some long pentatonic runs with similar phrasing to the Comfortably Numb licks. He rakes into notes on the first string as he did in the first Comfortably Numb break, but with this cleaner tone it has a staccato effect that complements the track’s disco feel. As the solo builds, he travels further and further up the neck, until he ultimately finds himself backed into a corner.

In an interview earlier this year, jazz guitarist and session legend Lee Ritenour revealed he was brought in to help Gilmour finish composing the solo.

It was largely complete when Ritenour first heard it, but Gilmour couldn’t figure out what to do for the last four bars.

“You ran out of room!” Ritenour recalls telling Gilmour. “He got up so high he had nowhere to go.”

Pink Floyd’s plan was never to release Ritenour’s takes, but to use them for inspiration. Ritenour says the idea to end with funkier, rhythmic phrases lower on the neck was his, although the licks Gilmour played were ultimately his own.

It was a smart move, tying the lead parts to the underlying chords as the track winds down.