“Because the guy’s got a knife, he’s fairly persuasive!”: How Paul McCartney survived a mugging - and a mutiny - to create his solo masterpiece

The full, amazing story of Band On The Run

High drama and dogged determination were defining factors in the creation of Band On The Run, the 1973 album by Paul McCartney and Wings which remains the most celebrated of his post-Beatles works.

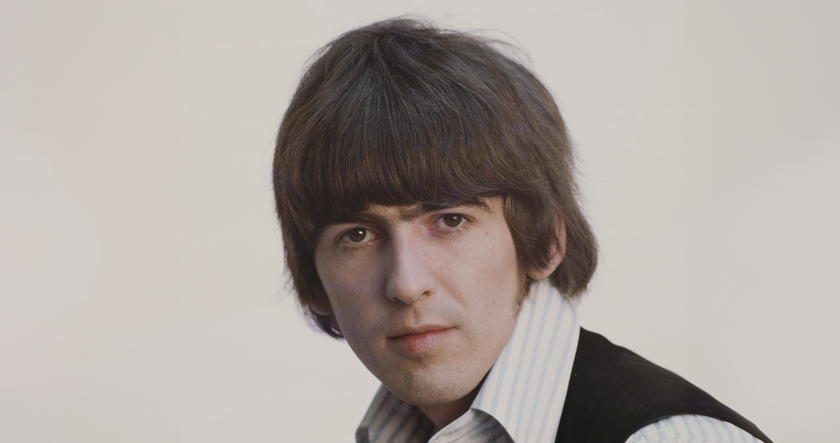

By 1973 he had released two solo albums, McCartney (1970) and Ram (1971) as well as two with Wings: Wild Life (1971) and Red Rose Speedway (1973). But none of these attracted the kind of critical acclaim received by his former bandmates John Lennon and George Harrison.

All that changed with the Band On The Run album. It is McCartney’s solo masterpiece and the jewel in its crown is the title track, with its majestic breadth and vision.

On this album, McCartney wanted to shake things up. “I was looking for something different and adventurous,” he told Dermot O’Leary in the 2010 documentary McCartney & Wings: Band On The Run. “I found a list of EMI studios. They had studios everywhere… in China, Brazil… but then they had one in Lagos and I thought, ‘That is so off the beaten track – something’s got to happen if we go to Lagos’.”

What did happen was a series of calamities. The first occurred the night before their departure for Lagos, when McCartney received a call to say that Wings’ lead guitarist Henry McCullough and their drummer Denny Seiwell wouldn't be coming.

"I wasn't cool about it, I was livid," McCartney told O’Leary. “The good thing about that was then it made me [think]... ‘Right, screw you! I am going to make an album that you wish you were on!.”

When the plane took off that morning in August 1973 there were only three remaining members of Wings on it: Paul, his wife Linda, and trusted right-hand man Denny Laine.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

One significant asset was Geoff Emerick, the young engineer from Abbey Road Studios who McCartney invited to Lagos to engineer the album. Emerick’s groundbreaking recording techniques had played a pivotal role on The Beatles’ albums Revolver (1966), Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (1967) and Abbey Road (1969), and his input on Band On The Run was invaluable.

But when he and Wings arrived in Lagos, they discovered that EMI’s studio was still being built and was ramshackle and ill-equipped. To compound problems, there were no recording booths in it.

There were further setbacks. Nigerian musician Fela Kuti visited the studio twice, reportedly convinced that McCartney was going to appropriate his music. Former Cream drummer Ginger Baker was also troubled. Baker had made the city his home and was reportedly irked that they weren’t using his studio ARC. Paul placated Baker by recording the song Picasso’s Last Words (Drink To Me) at ARC.

The drama continued when Paul collapsed one day. Linda suspected a heart attack but it was a smoking-induced bronchial spasm.

Then, in a darker turn, Paul and Linda were mugged at knifepoint while walking home from a friend’s house one night.

“A car just pulls up,” McCartney told Dermot O’Leary. “Suddenly all the doors open and five young chaps get out and there’s a little squat one who’s got a knife… So we said, ‘What do you want?’ Because the guy’s got a knife, he’s fairly persuasive.”

The McCartneys had been warned not to walk about after dark. On their return to the studio, the manager told them they were lucky to be alive.

Among the items stolen from them were demo tapes from the album, prompting McCartney to immediately record new demos from memory. This effectively gave the songs a second draft, which resulted in a leaner and tighter album.

The McCartneys, Laine and Emerick helped the studio engineers to build recording booths out of perspex and wood.

Reduced to a trio, they were forced to multi-task. McCartney took over duties behind the kit. “I’m an okay drummer,” he told Dermot O’Leary. “I’ve got a kind of style, I’ve got a feel and I like playing drums. So I knew if I kept it simple I would be able to cover it. So you’ll notice the drums on Band On The Run are pretty simple.”

Once the studio was up and running, Paul, Linda and Denny were an effective team. “Me and Paul, we had the same influences musically and had known each other since the ’60s,” Laine told Billboard in February 2023. “It was just easy. It was easy to get a good groove… We did it almost as though it was a home recording… and we kept it basic. No frills.”

They worked quickly, laying down the basic tracks for seven songs within three weeks. Laine played electric and acoustic guitar, Linda played keyboards and Paul covered everything else – drums, bass, percussion and lead guitars and additional keyboards. He also used his Fender Jazz Bass, a right-handed model strung left-handed.

The title track was inspired by a comment from George Harrison. “It started off with ‘If I ever get out of here’,” recalled McCartney in Paul Gambacinni’s 1976 book Paul McCartney In His Own Words. “That came from a remark George made at one of the Apple meetings. He was saying that we were all prisoners in some way, some kind of remark like that. I thought that would be a nice way to start an album.”

The idea of musicians portraying themselves as outlaws was gaining pace at that time. The Eagles had just released the Desperado album, with the band dressing up as outlaws for the sepia-tinged cover shoot.

“I think around that time there was a spirit among the young people of getting away, vigilantes, desperados,” McCartney told Dermot O’Leary. “There were records coming out a bit like that. And I think that was me doing a nod to that kind of thing. It was a nice idea, breaking out… we’re stuck inside somewhere… these four walls and then the song could break out.”

The song is essentially a three-part medley. The first section is a slow poignant ballad, the second has tension, anchored in a funk-rock groove, while the final section opens up into widescreen country-rock.

The distinctive lead guitar riff that opens the first section is a soulful entrance to the song, and is followed by a memorable synth motif from Linda on a Moog. Paul played acoustic and electric pianos on the track in addition to guitar, bass, drums, lead and backing vocals.

Like all great bass players, one of McCartney’s strengths is knowing what to leave out and his tasteful, restrained playing elevates the spaciousness within the arrangement.

38 seconds in and McCartney’s vocal enters the mix: “Stuck inside these four walls/Sent inside forever/Never seeing no one/Nice again like you, mama…”

By the third line there are rich, lush harmonies from Paul, Linda and Denny.

At 1:18 the whole thing steps up into the second section, with its lean, simple groove, punctuated by handclaps.

At 1:33 a squelchy refrain on the Moog can be heard over one of the key guitar patterns, anticipating the vocal melody at 1:48. “If I ever get out of here/Thought of giving it all away/To a registered charity/All I need is a pint a day.”

At 2:05, the whole thing shifts for the dramatic guitar, strings and brass on the stops and pushes of the instrumental break.

As the orchestration recedes, the strumming of a 12-string acoustic heralds the beginning of the third section, a pacy, uplifting country rock sound with a driving 4/4 beat. It’s a big, lush sound with nifty slide guitar flourishes and the 12-string acoustic at the fore.

While the first two sections of the song were recorded in Lagos, the third section was recorded on their return, in October 1973, at George Martin’s AIR Studios in London.

McCartney laid down the third and final section with a 60-piece orchestra and the person he asked to write the orchestral arrangements on the album was Tony Visconti, whose string arrangements on T. Rex records had impressed McCartney.

In his autobiography Bowie, Bolan And The Brooklyn Boy, Visconti recalled receiving a call one Saturday from McCartney, who asked him to come over to his St. John’s Wood home the following day.

“Paul sat at the piano with me sitting next to him and played me snippets of songs on a portable cassette player, while on a second one he recorded his comments and his piano doodlings for string ideas. I was thrilled to be doing this for one of my idols but not so thrilled when he told me he needed all seven arrangements by Wednesday.”

For two days, Visconti barely slept. He arrived at Air Studios on the Wednesday to be greeted by Paul, Linda, Denny, Geoff Emerick and a 60-strong orchestra.

“I’m sure I looked bedraggled, I definitely felt it,” he recalled.

Visconti was conducting the orchestra on all seven songs.

The strings and brass bring real grandeur and dynamism to the Band On The Run track, particularly on the interlude between the second and third sections. This was the first part they worked on that day.

“We just kept doing take after take until we got the transition to work smoothly,” recalled Visconti. “Only some of the sixty musicians were wearing headphones, so it was a genuine job of conducting to bring them in and to keep them together. The rest of the day went a lot smoother. For the most part Paul acted the jovial perfectionist, which made it all seem like fun.”

Band On The Run was released in the US on 8 April 1974 and was a massive hit, becoming McCartney’s third solo American chart-topping single and the second for Wings.

The US radio edit of the song was 3:50 long as opposed to the 5:12 length of the original. Later that year, the single was released in Britain and reached No. 3 on the UK charts.

In many ways, the challenges they overcame making the album were the very elements that helped them rise to the occasion and elevate this to a great work.

“I think if we’d have stayed in London and gone to our normal studio, it might have been an okay album, a good album,” McCartney told O’Leary. “But the fact that we were in a strange place, with strange things happening, there were now only three of us instead of five, we had to work round all these circumstances and incorporate all this into the album. Suddenly we were forced to. We had no choice.”

Neil Crossley is a freelance writer and editor whose work has appeared in publications such as The Guardian, The Times, The Independent and the FT. Neil is also a singer-songwriter, fronts the band Furlined and was a member of International Blue, a ‘pop croon collaboration’ produced by Tony Visconti.

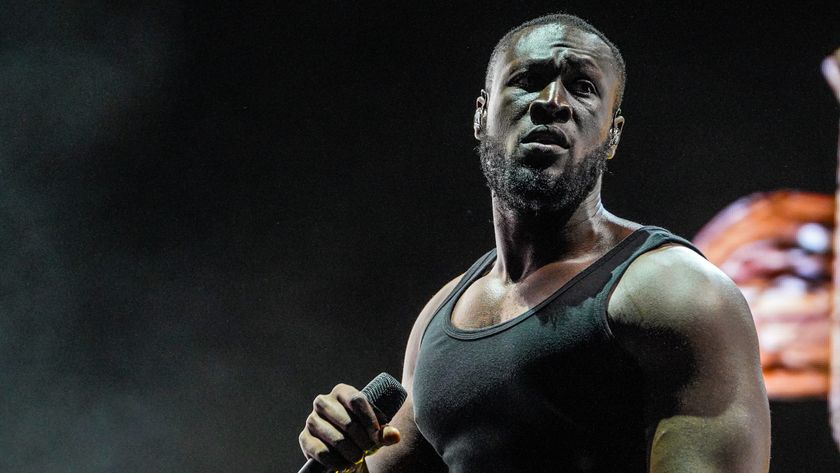

“In recognition of his outstanding achievements in the field of higher education, philanthropy and widening participation”: There’s another honorary degree on its way to Stormzy

“An ambition that has eluded us – until now. What a way to round off a tour and a career”: The ‘longest running pop band’ will end their career at Glastonbury

![Paul McCartney & Wings - Band On The Run [Rockshow] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/_m_6KvHSyx4/maxresdefault.jpg)