15 questions for... Orbital’s Paul Hartnoll and Murray Lachlan Young: "Sometimes nothing but a 303 will do"

You may well know Paul Hartnoll as one half of Orbital, the duo that caught the ear of a nation in the early ‘90s by channeling the nascent influences of house and techno into their own euphoric strain of UK rave.

What you may not know is that Paul’s latest project has seen him team up with poet, author and comedian Murray Lachlan Young for a “lockdown-inspired musical collusion.”

The record, The Virus Diaries, distills the insanities and inanities of the past year into 15 tracks that document the archetypal lockdown experience in darkly comic fashion.

Cycling through a variety of moods and emotions, Paul’s synth-laden instrumentals capture the spirit of pandemic-induced mania while providing a fitting backdrop for Murray’s tragicomic observations.

We spoke with the pair about the making of the album, getting an insight into the inspirations - both technical and conceptual - that drove their creative process.

1. Tell us how you got into music production in the first place?

PH: “When did I get into it? I’m thinking back to sitting in my brother’s bedroom - I think it’s my oldest brother Gary - listening to Autobahn by Kraftwerk when I was under the age of 10. Just being mesmerised by it, and thinking 'wow - what is this?' It was just brilliant.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

“I got into playing guitar first, but always had an interest in electronics along the way. I remember messing around and jamming with the same kind of people Murray used to interact with - a pair of brothers, the Ransom brothers, who used to run a successful local band called The Dream Clinic. I remember Mark Ransom had a synthesizer, an SH-101. It was absolutely mesmerising, just sitting there in a village hall, exploring that.

“Around that age I started working for my dad with my brother. He bought a drum machine, I had a guitar, then I bought a second-hand synthesizer, and I just started building up an arsenal of stuff.”

2. When did you start to feel you were getting somewhere?

PH: “I was always an arrogant little shit, so I felt like I was getting somewhere as soon as I started. [laughs] I don’t think arrogant is the word, more ignorant. I was quietly confident in the sense that I felt very strongly that this was the thing I was going to do. I’m not taking no for an answer. I got through it all on a wing and a prayer.

“I remember saying to people when we were queuing up to do our exams, when they asked what I’m going to do: I’m going to do music. They’d say that’s not realistic, and I’d say, you’ll see me on Top of the Pops in a year or two. It took a few more years, but I did achieve that in the end.

When I heard Detroit techno I thought, 'they’re my people, that’s my world. This is dark, a bit melancholy and a bit sad.'

“When house music came along, I thought 'I wanna do it my way', and incorporate all of the stuff that I liked: Cabaret Voltaire, this Sheffield industrial music. I thought house music could have done with a bit more of an industrial edge.

“A mate of mine gave a couple demo tapes I had to a friend of his, a pirate radio DJ who ran one of the most successful acid house shows in the South East. He played both of my demos on one of his shows when I was in sixth form college, and I just thought I’d made it - I thought I’d hit the big time. He was the guy, Jazzy M, who put out our first single, Chime.”

3. What is your overall music and production philosophy?

PH: “Try not to worry. Be yourself, be honest. If something excites you, go for it. That could be a good feeling, in yourself, or a sad feeling, or an angry feeling - that can spawn creativity. Equally, I can get that if I listen to a new artist I’ve never heard before. If the music’s really inspiring, that’ll make me think: that’s amazing, I want to do something like that.

“That’s what music is, it’s a game of creative leapfrog. We jump over each other’s backs all the time. It has to be a dialogue, it has to be a language that we all understand. Otherwise, it’s not music, it could just be noise.

“The trick is to find your voice amongst it. That’s what I had - like I say, with house music, it had too much of a soul music influence for me, I wanted to hear the darkness in it. And so I just started doing that myself, not realising there wasn’t really much of that going on.

"You end up filling a niche, like water finding its own level. When I heard Detroit techno I thought, 'they’re my people, that’s my world. This is dark, a bit melancholy and a bit sad.'”

4. How did this collaboration come about?

MY: “The pandemic had just kicked off, and it became apparent to me that there was a dropout in the context going on. Nobody had anything to grasp on to, there was just the stuff coming out of the mainstream media: stay in, do as you’re told, etcetera.

“Without any real thought attached to it, I wrote a piece calling Working from Home. I think the lack of context was being replaced by fear. So it felt to me that to write something humorous about what’s going on, day to day, would be a good idea.”

PH: “I think you sent me Working from Home."

MY: “And then we did Jogging and Baking after that. Paul put a soundtrack to it, so it was like a poem with a soundtrack. I’d started writing spoken songs, and Paul would send me BPMs. We got into something where we’d say: 'OK, here’s a subject this week'. The subjects were really clear. Suddenly, everyone was jogging and baking.

“The one after that was Shopping - walking down the street realising that there was this absolute fear, and shopping felt like some sort of covert act. So how do you turn the feeling of being really uneasy, everybody feeling freaked out, into something that expresses that darkness and humour at the same time?

“I asked Paul for a click, then wrote the pieces to Paul’s BPMs, then sent them back. Then Paul did each of the tracks in about 24 hours. Each track, from the concept through to the realisation took about 48 hours. There was no second guessing, no time to question anything. Everything came out very naturally.”

5. How do you think the conditions imposed by the pandemic affected your creative process?

MY: “It was interesting, because I spoke to a lot of creative people at the time, and nobody was doing anything, everybody just shut up shop. As far as my creative process, The Virus Diaries seemed to kick something off. It was a really big, powerful creative period for me.

"It’s about movement, creativity, and once you’re off and running, it’s great - and then you stop, and it’s harder to get the ball moving again.”

6. Were there any bits of gear or studio equipment that were fundamental to the making of this record?

PH: “Yes - the Korg Minilogue. It’s a piece of kit that I bought a while ago and didn’t end up using that much, because I buy too much equipment for my own good. When I came to set up this studio, for the lockdown, I rushed to my main studio and chucked a load of desert island synths in the car.

“I looked at things like the Minilogue and thought: 'I haven’t really used that, why don’t I set that up and learn to use it during the lockdown?' The same goes for another Korg synth, the Wavestate, which is an update on something I used in the ‘90s a lot, called the Wavestation. Then there’s the Elektron Analog Rytm, I used a lot of that.

Just yesterday I had to rush down to the studio because I was missing the Roland TB-303 - sometimes nothing but a 303 will do.

“I also went back to my old favourite, which is sampling, I love sampling. I don’t know why, I felt like this was a sampling project - that kind of cut-up, hip-hop, old-fashioned house music kind of vibe. It’s quick - you just grab something, sample it, make something crazy out of it and it fills a space.

“It’s actually got me back into sampling again - I collect ridiculous amounts of analogue synths, and synths are synths, but sampling’s a whole different world.”

7. Where are you finding your samples?

PH: “Literally anywhere. I love sampling unhip, uncool easy listening Latin music, I sample things like that all the time. The music has lots of space, and it’s really beautifully recorded. I normally buy them from second-hand shops for about two pound, and pick the records purely on the cover.

“I also go out into the world and do lots of field recording with my little Sony recorder. I’ll go to places that sound interesting - Newhaven Fault is a favourite of mine, it’s got these huge concrete reverberating tunnels. You hit a big metal bar at one end and it just sounds amazing down the other.

“Recently I’ve been trying to sample things that mean something to me, places where I grew up. The subway tunnel where I used to do my underage drinking and smoking, recording sounds in there, making drum kits out of hitting the light fittings and bannister rails. For me, these sounds have a resonance to my past and mean something to me. There’s a pure joy in that, it makes you feel good.”

8. What pieces of gear in your studio are most important to you?

PH: “Currently, it’s my ARP 2600, I’m using that a lot. I’m using my Macbeth M5N, and my Roland System 100M, they’re my favourite go-to analogue synths for big fat monosynths.

"For a polysynth I’ve got a Jupiter-8 just behind me, which I use a lot. Thinking about modern synths, I’ve got the Waldorf Quantum, which is a kind of sampling wavetable synth, very digital if it wants to be, but a sampler as well.

“Just yesterday I had to rush down to the studio because I was missing the Roland TB-303 - sometimes nothing but a 303 will do. And within arm’s reach over here is my 909, which I’ll never let out of my sight.”

9. What’s on your gear shopping list?

PH: “I’d love to have a Prophet VS, I’d love a big fat old Oberheim. I could buy synths forever, I’d love a Buchla. I love it all, I’d have one of everything - in fact I’d have two of everything.”

10. What are your favourite plugins?

PH: “During the lockdown I really focused on certain bits of software and properly learned how to use them. I’ve been using Ableton 11 - I was beta-testing that throughout the lockdown, which was brilliant. I’ve been using Native Instruments for mixing, their Vintage Compressors and their Solid Mix Series plugins.

“I’m also using plugins from Sonic Charge and Soundtoys. Valhalla reverbs are my favourite reverbs. I always use a bit of iZotope Ozone 7 for mastering if I’m demo-ing something. I’ve been using Arturia synths, I love their Pigments.

“I try not to overload my system with too many plugins, and I try not to use too many soft synths. Not because I don’t like them, but because I’ve got so many of these big blunderbusses here, it just seems foolish not to use them.”

11. How do you tend to start a track?

PH: “I start with an idea. I sometimes have musical ideas which I record into my phone, which is me singing, and then I’ll go and translate that into synths. I never usually sit down with a blank canvas anymore, I’ve always got something in mind. Sometimes when I’m in the flow, something just happens and I realise I’ve started something new without realising.

“If you start with the main idea, the main thrust of a song, you’re more likely to get a good result than if you just start with a groove or a beat. It’s easy to make a beat when you’ve got a good idea, but it’s not always easy to find a good idea to put over a beat or a groove. I try to start from the top down nowadays.”

12. How do you know when a track’s done?

PH: “You know you’re finished when you start to doubt things: 'oh, I wonder if this is right, I wonder if I’ve done this before, I wonder if people will like it.' Just walk away; it’s probably done at that point. If it isn’t, go away, make a cup of tea and come back.

"Try and finish it quickly; good things are done quickly. Anything you have to labour over is probably not brilliant.”

13. Are you planning to perform any of the material from this album live?

PH: “It would have been fun - I would have quite liked to have done it at least once. We probably would have done it in the Sleaford Mods way, though, not in an Orbital way. I would have taken a laptop and DJ'd the backing track, and let Murray be the cutting edge of the band while I stand at the back.”

MY: “I’ve got a gig this weekend, at some secret thing down in Cornwall - I’m going to perform Shopping from the album, so that’ll be the first live performance, but Paul won’t be there. He’s too grand and important. [laughs] Come on Paul, come down to Cornwall for a weekend and get paid no money to do one track."

PH: “The way this lockdown’s going that sounds pretty good to me.”

14. What have you picked up from being in the industry that you can pass on?

PH: “Don’t have a fallback plan. If you’ve got a fallback plan you will take it, ‘cause it’s a shit business. [laughs] No, it’s not a shit business, but it’s hard getting into this world. Anyone I know who had a fallback plan took it.

"The people who made it were the quietly confident people who just got on with it. I think that’s it - it sounds a bit Disney, but you’ve got to believe in yourself, do you know what I mean? Because nobody else will. Apart from your mum, of course.”

It’s all about failure. You can’t understand success unless you fail, and you can’t grow unless you falter.

MY: “The concept of success is a very abstract thing. People see success as either having loads of money or holding up a thing that somebody gave to them that says they’re successful. Success is being true to yourself and what you’re doing, and it doesn’t necessarily have to mean having a platform.

“Of course it would help to have a million people streaming your stuff - but to be an artist producing work which has integrity, means not producing work that you think other people will like. It means producing work that you think is good, that resonates with you on a soul level.

"The important thing is not to second guess yourself, and not to do what you think other people will want. The key is finding your own voice, that’s what will make you into somebody.”

PH: “If you fail by being true to yourself and doing what you want to do, it’s an easy failure. You can accept it. If you spend all your effort being calculated, trying to copy something else and do what you think people want, and you still fail, you’ll be gutted.”

MY: “Samuel Beckett said 'fail, fail again, and fail better.' It’s all about failure. You can’t understand success unless you fail, and you can’t grow unless you falter.”

15. What do you both have planned for the near future?

MY: “I’ve got an album which has been rattling around for a while, but we’re getting there. It’s me and Lu Edmunds from The Damned and Public Image Limited, and a guy called Mark Roberts, who’s the live drummer for Massive Attack.

"They’ve got a band called Blabbermouth and I’ve recorded an album with them; we’re going to release that as a book-stroke-CD, believe it or not - apparently people are buying CDs. Can you believe it?

“Then I’m doing a jazz/spoken word album with my son - my son is a producer, a 21-year-old producer. That’s a really exciting thing, to get to a point where your son is saying 'this is what we’re doing', and he’s the boss. It’s great.”

PH: “I’m working on the score for a Netflix TV series, which I can’t talk about. What I’ve seen so far is amazing, that’s going to be a big show next year. I’m also working on two different Orbital albums.

"One was supposed to come out before lockdown, 30 Years of Orbital. Remixes, old out-takes, and some new stuff, a celebration of 30 years. That’s been delayed and delayed, and will now have to be 30-something, rather than 30. Then hot on the heels of that, a new Orbital album.”

Hartnoll & Young's The Virus Diaries is out now on Hartnoll & Young Records.

I'm MusicRadar's Tech Editor, working across everything from product news and gear-focused features to artist interviews and tech tutorials. I love electronic music and I'm perpetually fascinated by the tools we use to make it. When I'm not behind my laptop keyboard, you'll probably find me behind a MIDI keyboard, carefully crafting the beginnings of another project that I'll ultimately abandon to the creative graveyard that is my overstuffed hard drive.

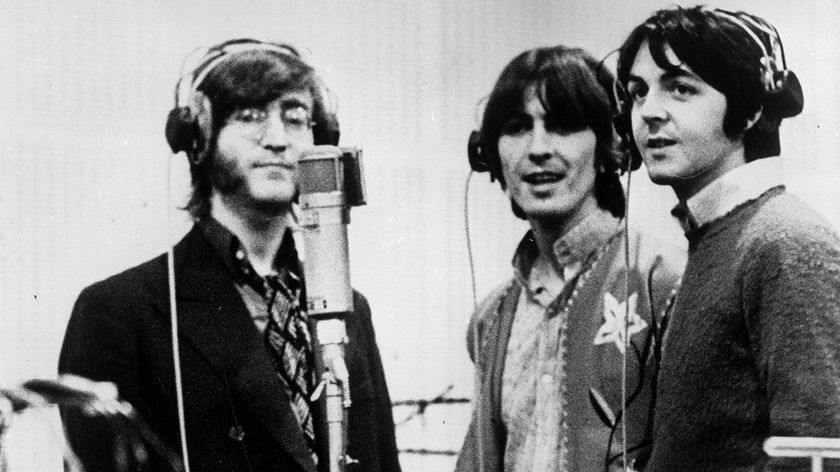

“I didn’t even realise it had synthesizer on it for decades”: This deep dive into The Beatles' Here Comes The Sun reveals 4 Moog Modular parts that we’d never even noticed before

“I saw people in the audience holding up these banners: ‘SAMMY SUCKS!' 'WE WANT DAVE!’”: How Sammy Hagar and Van Halen won their war with David Lee Roth

![Chris Hayes [left] wears a purple checked shirt and plays his 1957 Stratocaster in the studio; Michael J. Fox tears it up onstage as Marty McFly in the 1985 blockbuster Back To The Future.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/nWZUSbFAwA6EqQdruLmXXh-840-80.jpg)