10 old-school sampling tricks that will never go out of style

Classic effects and techniques brought bang up to date for the modern producer

Though sampling technology has progressed massively over the past 30 years, and contemporary software can do a whole lot more than the hardware it's replaced, it would be naive to assume that the techniques used by the old-school pioneers are redundant, too.

In fact, it was undoubtedly the limitations of their gear that compelled these producers to be so creative with their sampling - and they came up with some wild and wonderful sounds as a result. So, let's look back at how these early sampling wizards pulled off their most famous tricks, and then find out how you can recreate their techniques using modern software.

1. Time to pitch

Although rudimentary timestretching was a notable feature on early samplers, it didn't often produce the desired results. To match up a sample's timing with a track, producers would simply play it at a lower or higher note, to slow it down or speed it up.

Of course, this would also change the pitch of the sample - leading to the high-pitched chipmunk vocals found in early jungle and hardcore music. Sometimes, though, this method can sound better than even the best modern warping techniques, particularly on drum loops, as it reserves transients perfectly and creates a punchy sound.

Try to get your drum loops in time by tuning them up or down (using your software sampler's re-pitch mode) first, then resample them at that speed before editing further.

2. Gated trigger

New tech brings us new genres, and the early '90s brought us both jungle (the precursor of DnB) and affordable time-stretching. Not only did this make it possible to take a vocal and add it to a track at a completely different tempo without making it sound like a meerkat on helium (or the devil drunkenly slurring), but also led producers to realise that by halving the tempo, then halving it again (and so on...), they could create slowed-down versions of words and phrases.

This process duplicates slices of the sample in question, creating a gated, stuttering effect - an almost sonic-strobe-like sound - and it still sounds wicked today.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

3. Flip it and reverse it

For nearly as long as people have been sampling sounds, they've been reversing them. Reserved sounds can be great for edits, and can even form an integral part of your rhythms. Reversed percussion hits like hi-hats and claps can feed into the unreversed hit for more emphasis, or even just sit within the rhythm and give the groove some more body.

It's usually best to place them so that the end of the reversed sound lines up with a division of the beat, even if there's no other hit occurring at the same time. If a reversed sound doesn't end on a beat, try adding another percussive element at that point to better maintain the groove.

4. SP-1200 bass

Vintage samplers were nothing if not quirky, so it's worth brushing up on the idiosyncrasies of the gear behind your favourite classic tracks. For example, early-'90s New York hip-hop was loaded with grimy, filtered basslines, thanks in part to a quirk of the E-MU SP-1200, as Public Enemy producer Hank Shocklee told The Village Voice.

"One day I was playing Black Steel in the Hour of Chaos, and it came out real muffled. I couldn't hear any of the high-end part of it. I found out that if you put the phono or quarter-inch jack halfway in, it filters the high frequency. Now I just got the bass part of the sample. I was like, 'Oh, shit, this is the craziest thing on the planet!'"

To recreate this sound, simply add a low-pass filter before your bitcrusher in the effects chain.

5. Creative limitations

Early digital technologies had memory limitations that we'd consider ridiculous now. Back in the day, sampling time came at a premium that we're not used to anymore, but this was the catalyst for some pretty inventive techniques, which in turn resulted in some unique results.

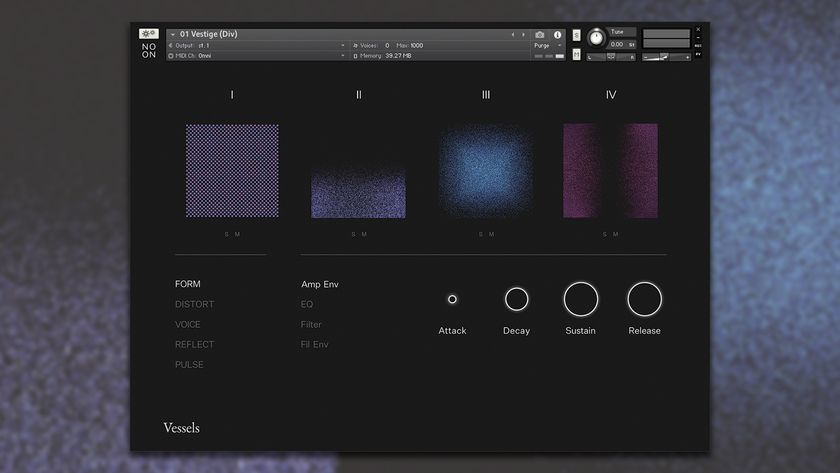

Memory could be saved in many places. In order to achieve sustain, for example, it was necessary to use just a short looped section of the sample. When you pressed a key, the attack phase would be played until it reached this looped section, which then continued to play until the key was released, at which point the sample would play from the looped section to the end.

This looping effect was often imperfect and - more importantly - noticeable, becoming a key part of the character behind many early sample-based riffs, such as the ubiquitous car horn noise popularised by Todd Terry. This memory limitation, in partnership with low-resolution editing, meant that the sound of the short loop could be hard to conceal, but one way to deal with this is to throw caution to the wind and use the effect as an overt characteristic that adds to the vibe of the track.

6. Sine of the times

Akai's early S900 and S950 samplers were famously prodigious synth bass monsters. Switching on either machine yielded a default sample of a simple sine wave bass, which became synonymous with early hip-hop, hardcore, jungle and DnB.

Sine wave bass is notoriously difficult to make interesting, but a combination of 12-bit circuitry and less-than-transparent analogue outputs added real oomph. You can recreate this by running a sine wave riff through a bitcrusher and some analogue saturation plugins. The difference may seem subtle at first, but try throwing it into a track with a few other elements.

7. Combined methods

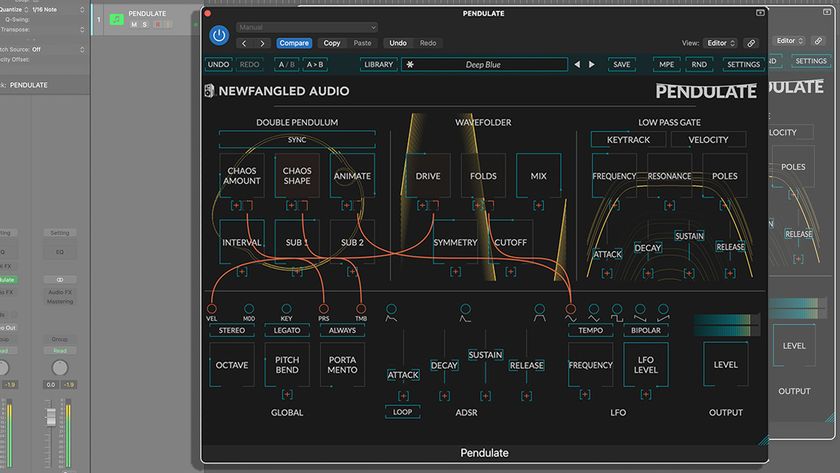

Some early sample-based machines, such as Roland's D-50, combined synthesis and sampling. This was partly for creative reasons, but also partly to overcome the limited sampling time available.

This technique can produce layered sounds such as percussive strikes and attack phases (that need not change pitch when they're played up and down the keyboard) over sustained sounds that can be played musically.

Try your own combinations by mapping two different sounds to the same key-range in your sampler and adjusting their respective envelopes. For example, the attack portion of a piano with the sustain of a trumpet sample. Or a kick sample and an electronic organ, Daniel Bedingfield-style.

8. Cut the chord

A classic sample-riff effect is to sample a chord and then play a riff as if using a regular synth patch. Two things happen here: the length of the sample changes (higher notes are shorter, while lower notes get longer), which can have a dynamic effect on the groove; and the actual sound can be rather interesting, as real players don't usually play riffs by transposing all the notes of a given chord up and down in identical semitone intervals.

Recreate this effect by recording a chord in the sound of your favourite synth patch, loading that recording into a sampler, and get busy creating a riff with it.

9. Vocal tricks

The '80s saw a new kind of vocal sound taking popular music by storm: the sampled vocal riff. Whether your first introduction was Whistle's Just Buggin', or Stock Aitken and Waterman's production of Mel & Kim's Respectable, this distinctive sound was all over the charts.

By the mid-'90s, it was all but dead and buried - a corny anachronism born of naïvety and new technology- but then a couple of years ago Major Lazer brought it back, starting with Pon De Floor - subsequently sampled for Beyonce's Run the World (Girls) - and continuing right up to their hit collaboration with DJ Snake and MØ, Lean On.

The approach used in the latter track utilises heavy pitch modulation, but it's essentially the same simple trick: take a word or syllable from a vocal, map it across the keyboard and make a hook out of it.

10. Break stuff

A defining feature of early jungle sampling was the slicing, dicing and re-ordering of drum loops, achieved by chopping a beat into chunks and triggering each one in succession via MIDI. Tracks like DJ Seduction's Sub Dub created the blueprint for DnB to come by varying the playback pattern in each bar constantly over the space of 8, 16 and even 24 bars.

This was achieved in a number of different ways, the first of which was by carefully chopping a one-, two- or four-bar break into parts, with different start points for re-triggering from (choice snares, kicks, 'shuffles', fills, etc).

Alternatively, it can be achieved by copying the same break to between five and ten adjacent keys, and setting a different sample start point for each key (again, choosing percussive hits like kicks and snares).

Another way to do this is to simply slice the loop into quantised measures (eighth-notes, quarter-notes, half-notes, whole notes, etc), complete with off-grid glitchy attack phases and some sliced 'air' to open up the loop.

Computer Music magazine is the world’s best selling publication dedicated solely to making great music with your Mac or PC computer. Each issue it brings its lucky readers the best in cutting-edge tutorials, need-to-know, expert software reviews and even all the tools you actually need to make great music today, courtesy of our legendary CM Plugin Suite.