The Radiophonic Workshop's Paddy Kingsland discusses life, the universe and everything

The groundbreaking music boffins who scored our childhood are back for the 21st century

Some time back in the late '50s, that uniquely conservative and straight-laced institution the BBC began producing some of the most weirdly wonderful, avant-garde electronic music that had ever wafted across the British airwaves.

A small team of white-coated musicians and techno-boffins known as the BBC Radiophonic Workshop was originally commissioned to create sound effects and theme tunes for radio, but they soon branched out into TV, providing, most notably, the space age gloops and whoops for one of the most iconic theme tunes of all time: Doctor Who.

Throughout the '60s, much of this groundbreaking work was achieved with recordings of everyday objects and simple tape manipulation, but the results went on to inspire generation after generation of musicians, from Pink Floyd and the Stones to the Human League and Orbital. The NME called them "the British Kraftwerk"… Mixmag reckons they're the "unsung heroes of British Electronica".

Paddy Kingsland joined the Workshop - which included the late Delia Derbyshire (forever associated with the Doctor Who theme), Dick Mills, Brian Hodgson (the man who created the voice of the Daleks and the sound of the TARDIS) and John Baker - in 1970, coinciding with the arrival of commercial synthesisers. Although not every member of the Workshop embraced this musical revolution, Kingsland and the team were by now producing literally hundreds of soundtracks, themes and effects, some of which - like Kingsland's work on The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy - are regularly namechecked by modern day producers.

Sadly, budget constraints and technological changes put an end to the Workshop in 1998, but in 2009, Kingsland reunited with fellow Workshoppers Dick Mills, Peter Howell and Roger Limb, and Workshop archivist Mark Ayres, for an eagerly anticipated live concert at London's Roundhouse. Calling themselves simply The Radiophonic Workshop, and later joined by The Prodigy's drummer, Kieron Pepper, they've played a string of festival dates over the last two summers, including a joyous show at this year's Glastonbury.

"All my mates were killing themselves laughing," says 67-year-old Workshop spokesman Paddy Kingsland. "Us lot on the same bill as Metallica and Skrillex? Crazy!"

Much of the Workshop's original music was reissued on vinyl last year, but the British Film Institute's recent Days of Fear and Wonder season saw the DVD release of cult 70s kids' sci-fi series The Changes and The Boy from Space, complete with their Paddy Kingsland soundtracks.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Kingsland still runs the West London studio he set up after he left the Workshop in 1981, and he invited us down to watch the current 'band' rehearse for a series of forthcoming live dates.

People might suspect that the Radiophonic Workshop is only interested in vintage analogue synths and reel-to-reel tape machines, but there's plenty of digital gear scattered around the studio…

"We're not anti-computers or anything like that! My current setup is a Mac mini running Pro Tools 9. Yes, there are a lot of analogue synths on stage when we play live, but I also use plugins and VSTs… like the Arturia V Collection. And I'm currently looking at Mainstage, so I can set up a much more portable live rig."

You arrived at the Workshop at the same time as the first synths, but not everyone welcomed the synth invasion, did they? Delia Derbyshire is reported to have said that was when the Workshop began to lose its edge.

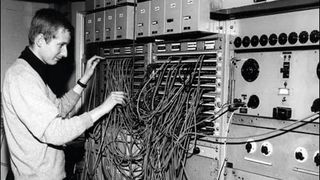

"The funny thing is that each generation takes music technology and runs a little bit further with it. The first time I saw the Workshop, it was literally tape machines - John Baker had a Leevers Rich machine with a varispeed that was graduated in semitones. There were hand-built oscillators, plate reverbs, echo chambers, a strange device called a PA Stabiliser that was misused to provide phasing and flanging; a very bizarre tape machine called the Tempophone that could vary the pitch of something without affecting the tempo and vice versa. It was all very, very basic, but the likes of John, Dick and Delia were creating incredible pieces of music. They were doing something that hardly anybody else in the world was doing.

"John, Dick and Delia were creating incredible pieces of music. They were doing something that hardly anybody else in the world was doing."

"Then, along came the synths and some rudimentary sequencers, which allowed me, Peter [Howell] and Roger [Limb] to run with the ball in a different direction. Yes, a lot of musicians were worried by the arrival of the synth, but as far as I was concerned, it allowed you to create sound quicker, and that was hugely important when you had two days to come up with a theme tune for a new science programme.

"Like I said before, each generation takes what's out there and uses it. Today I use soft synths; I use onboard Pro Tools compressors; I use the Structure sampler… It would be foolish to say, 'I will only use analogue gear'.

"Believe me, analogue gear is not without its drawbacks. The wonderful EMS VCS-3 was the first synth to arrive at the Workshop, and the pin-board controller was brilliant for teaching you how synths worked, but tuning-wise, it was all over the place."

You were one of the first people to seriously use synths in this country and, these days, you also use Arturia's V Collection. Do soft synths sound as good as the real thing?

"In my opinion… yes - in terms of pure sound, you can get something that's as good. I've got a real Prophet and I've got the Arturia Prophet, and they're very similar. The only thing I don't like is fiddling around with a mouse; the real one is easier to work on, but the payoff is that you get a ton of great synths inside your computer, and the whole thing sits right there on your desk."

"Eventually, I bought my three-grand Mac - I wish I'd bought three grand's worth of Mac shares, too; they'd be worth a few bob!"

When did you switch over to Pro Tools?

"Around 1993, but the switch wasn't an easy one. Let's just say that, in the early days, I was a reluctant Pro Tools user. I was using an Emulator/Radar 24-track setup, which was fine for the work I was doing, and I knew it would be a nightmare to change over to a totally new system. But my friends in the business were all saying, 'Look, get yourself a Mac. In the future, everyone will be making music this way.'

"Eventually, I bought my three-grand Mac - I wish I'd bought three grand's worth of Mac shares, too; they'd be worth a few bob! - and Digital Performer. And, like everybody else, I spent the next couple of years screaming at the screen while this whole new way of working was going through development nightmares. Suddenly, there was a combination of software and hardware, and no one wanted to take responsibility for anything that went wrong. It was always somebody else's fault."

When we were first talking about this feature, one of the key topics we wanted to cover was how the actual process of sound design has changed over the years - from tape manipulation, through synths, then samplers/sequencers and onto DAWs/plugins. You witnessed each of those changes and, indeed, created some of the most era-defining sounds. Would you say that modern tools make sound design easier? Or is that impossible to answer?

"We used to work with a brilliant producer back in the 70s called Arthur Vialls, who was involved in schools radio. One day, he came down and said, 'We're going to make a programme about what it would be like to shrink a little boat and go inside the human bloodstream. Can you give me some sounds and some music?' We created some shrinking sounds on a synth and then slowed down some bubbles for the trip down the vein. He loved it!

"Would it have been easier to make those sounds today? Probably. But there's a bigger question about whether the sounds you've created actually do the job they're supposed to do. For instance, when we did Hitchhiker's Guide, we sat down, ran the tapes, and we 'designed' sounds that fitted in with what was happening. We worked with timings to make the comedy better. It wasn't just about technique and experimentations in sound… there was an artistic side to what the Workshop did, and that's what a lot of people forget."

Absolutely! You've only got to listen to Delia's work on the Doctor Who theme, John Baker's Festival Time or your Logopolis soundtrack…

"It's very kind of you to put me in that list. No matter what equipment is being used, there will always be imaginative use of sound. If you listen back to the old Tom and Jerry cartoons, you'll hear some wonderful stuff. The parp of a car horn when someone falls over helps make that scene funny… but add a bass drum and a cymbal and it's instantly funnier. That leap of imagination can happen in any era with any set of tools.

"Delia did incredible and beautifully artistic work with sound in the early days of the Workshop. I'm sure that if she was still with us and opened up Pro Tools or Logic tomorrow, she would still be doing something that would make people sit up and listen."

You've been involved in electronic music for…

"Well, I joined the Workshop in 1970, but I was building amps and electronic organs even when I was a kid."

Are you surprised by the giant leaps that have been made in music technology?

"No, not really. Going back to that time, when I was a young boy building my electronic organ, I had a book called something like 'The Boys' Book of Technology'. It was a wonderful book full of information about computers, TV, radio, valves and transistors; and in the intro, it said that technology is in its infancy. I can still remember this! It said, imagine a mile and then put a one penny piece at your feet. That is how far we've come and how far we've got to go. That book was right. Lord knows where we're headed from here, but… isn't it exciting?!"

Computer Music magazine is the world’s best selling publication dedicated solely to making great music with your Mac or PC computer. Each issue it brings its lucky readers the best in cutting-edge tutorials, need-to-know, expert software reviews and even all the tools you actually need to make great music today, courtesy of our legendary CM Plugin Suite.

Most Popular