The 21 most important products and innovations in music technology history

From the mic to the MP3, we countdown the biggest tech breakthroughs of all time

The history of music is the history of music-making technology - they are inextricably linked and have been since the first would-be drummer banged a couple of rocks together back in the Stone Age.

15 'groundbreaking' music technology products that could have been classics but weren’t

From Pythagoras's experiments with hammers and anvils to Bartolomeo Cristofori's pianoforte, new and innovative ideas and technologies have consistently provided musicians with inspiration. Show a composer a new musical tool and they're going to put it to use.

Instruments like the harpsichord and piano were high tech revelations in their day - no less so than the miraculous hardware and software we currently use. The line between low and high technology is constantly shifting and nigh impossible to pin down.

However, for the sake of brevity, we've somewhat arbitrarily decided upon the use of electricity as a means to define 'modern' technology. Even so, our list is far from comprehensive, and you'll almost certainly think we've left out something that should be included while praising something that seems unworthy of the honour. Needless to say, we invite your comments and encourage you to share your own lists.

Picking the single most important innovation was always going to be difficult - however, our rankings are based on your votes, so at least the people have had their say. Who's to say, though, if ours is the worthiest winner - or if an even more significant innovation might be just around the corner?

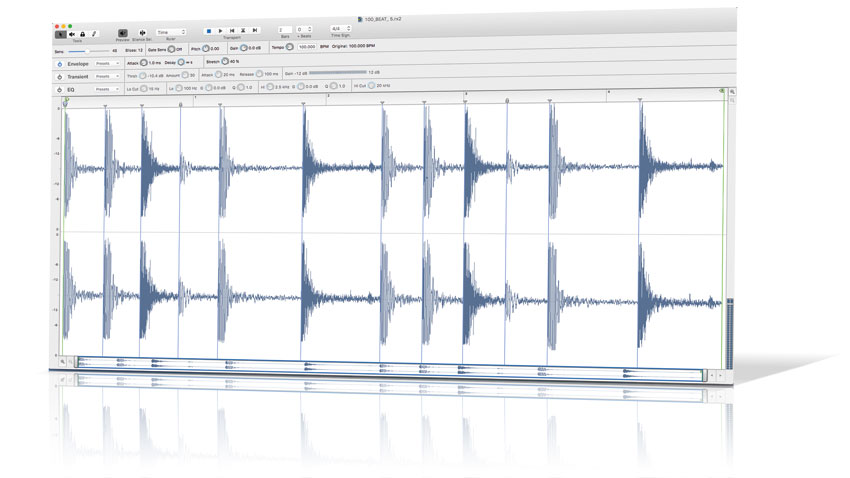

1. Beatslicing software

It's hard to imagine a time when chopping and slicing beats wasn't an integral part of the production process. Yet before Propellerhead's groundbreaking ReCycle program arrived in 1994, matching the tempos of sample loops could be a nightmare and, even then, altering a loop's tempo would likewise change its pitch.

The original version of ReCycle was a collaborative effort between the Props and Steinberg, and it allowed Windows and Mac users to avail themselves of a sophisticated transient detection algorithm that could seek out the attack transients of a beat and place slice markers accordingly. The results could be saved as a REX file and offloaded into the sampler of your choice where each slice would be mapped across the keyboard. An accompanying MIDI file could then be used to play back the slices at varying tempos. All in glorious mono.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

It was, at the time, a breathtaking technological achievement, and variants of the technology followed, not least being the stereo-capable Recycle 2. Eventually, most DAWs would have some form of beatmatching built-in (many directly supporting REX files), with Propellerhead's own Reason including the Dr. OctoRex player.

2. The guitar combo amplifier

It isn't rock 'n' roll if it isn't loud, and it isn't loud without amplification. Once again, George Beauchamp and Adolph Rickenbacker get the credit here. Their Electric String Company had all sorts of electrified instrument designs to its name, and they all required amplification.

They enlisted a fellow named Van Nest to design and build the first production unit, in the unassuming environs of his radio shop in Los Angeles. Eventually, Ralph Robertson was brought onboard to help develop a new line of amps, released in 1941.

Though tame by today's standards, the Rickenbacker amps made a big noise, influencing a burgeoning market. Leo Fender, for one, took notice and, with engineer Don Randall, set about creating the Super Amp in 1949, a unit capable of producing some actual volume.

It was also the perfect companion to Fender's solid-body electric guitars, not to mention Gibson's Les Paul, which would be released shortly thereafter in 1952.

3. Tape echo

Magnetic tape, of course, appears elsewhere on our list. But as with any new technology, there were those who saw in it something more than its intended use.

Forward-thinking experimentalists like Karlheinz Stockhausen and Edgard Varèse were using tape in a compositional context as early as 1950. Equally significant uses were being explored by both musicians and studio engineers, who had begun using tape to simulate echo in the studio.

The breakthrough, though, came in the form of Ray Butts' 1953 invention, the EchoSonic. It was the first commercially available tape echo unit, and was adopted and used by Elvis Presley's guitarist Scotty Moore, to name but one influential plank spanker.

Other tape echoes would follow, not least being the Maestro Echoplex. For our money, the tape echo earns its place on the list for its role in predicting modern production techniques. With the advent of the tape echo, electric music began to hint at electronic music, though that era was still a decade away.

4. The modular digital multitrack recorder

The late 1980s and early 1990s were a transitional period for music technology. This writer can clearly remember attending an industry convention at which a common topic of conversation was the direction of digital recording technology. DAT machines were in common use as mastering decks and various options for digital multitracking were being showcased. Which would become the standard? Would it be magnetic optical disks? Hard disks? Digital tape?

We all know the answer now, but back then it wasn't so cut and dried. However, when Alesis unveiled their ADAT recorder in 1991, it seemed that, for a time, digital tape would rule the future of recording. The ADAT machines squeezed eight tracks of 16-bit audio onto, of all things, a Super VHS video tape cassette, and up to sixteen of the machines could be synchronized for a whopping 128 tracks. Better still, each unit cost a mere $3995, far less than a quality analog 8-track machine.

Other manufacturers followed suit, licensing the ADAT tech (Fostex) or creating their own version (Tascam's DA-88). Would-be studio owners snapped 'em up and installed them in bedrooms, garages and basements, creating what would come to be called 'project studios'.

5. Physical modelling

This one is a bit tricky to place on the timeline. Probably the most significant development occurred back in 1983 when Alexander Strong and Kevin Karplus came up with their method for mathematically simulating the behaviour of a plucked string using software. They made use of an exciter (noise) fed into a delay, which in turn was fed through a filter. Both dry and delayed, filtered signals were fed back through the delay line, producing a simulation of a vibrating string (called a 'resonator' in modelling-speak).

However cool the idea, mathematically modeling the behaviour of an acoustic or electric instrument requires significant processing power, and the first mass-produced modelling instruments wouldn't hit the stores until 1994, when Yamaha released the VL1, an instrument that offered convincing brass and reed models for a staggering £3999. A year later, Korg's Prophecy combined modelled analogue synthesis with brass and reed models for a quarter of the price.

At the time, these instruments were exotic one-offs, and it would be many years before physical modeling would become commonplace, thanks to the power of the desktop computer.

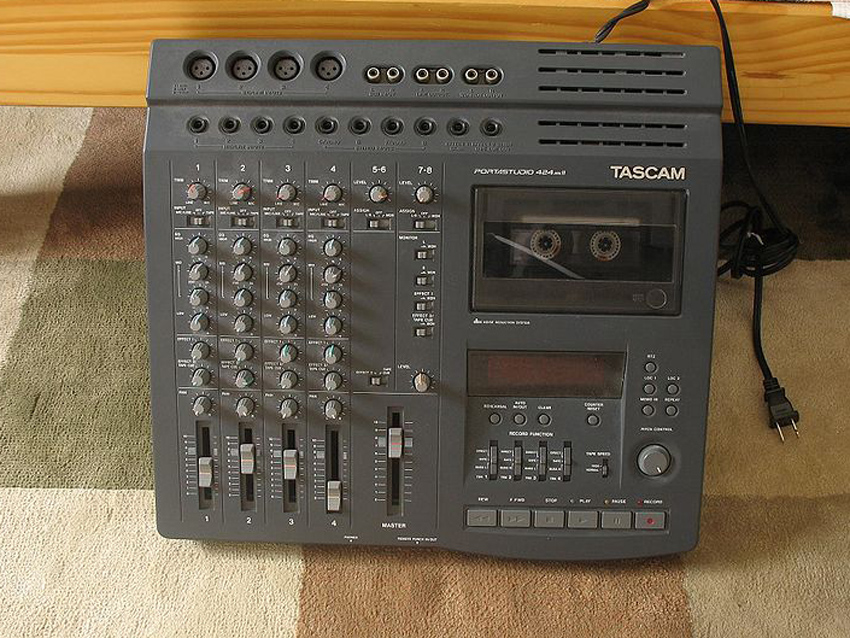

6. The 4-track cassette recorder

Though the 1980s are often seen as the era of digital music technology, one of the most important innovations of the day was very much analogue and very much low-tech. We're speaking of the 4-track cassette 'Portastudio'.

The first Portastudio (the model 144) was released by Tascam in 1979, and it signaled a revolution in independent music, bringing multitrack recording to the home studio. Four tracks wasn't much, but it allowed a bit of overdubbing and, if you were careful, you could bounce your first three tracks down to a fourth without too much sonic degradation, freeing up another three tracks for more overdubs.

Soon, a vast cassette trading subculture sprouted up, with musicians around the world sending tapes back and forth via the post. Some now-famous bands (Tall Dwarfs, The Legendary Pink Dots) got their start using 4-track cassette machines, and Bruce Springsteen used one to make his Nebraska album.

4-track machines would undergo something of a popular resurgence in the late 1990s and 2000s amid (and partially in reaction to) the computer music revolution. If you ask us, they're still worth exploring!

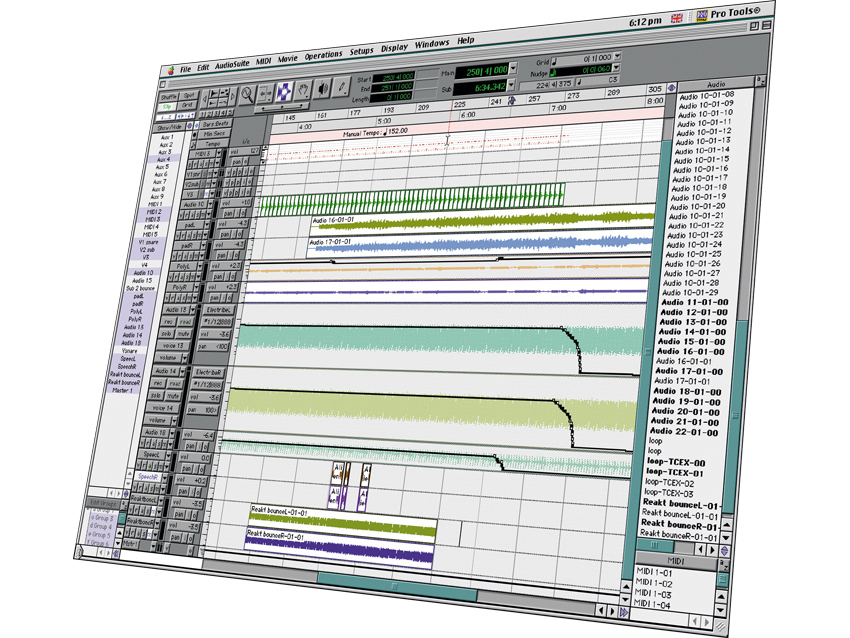

7. Hard disk recording

Hard disk recording began to see use as early as 1982, when New England Digital offered direct-to-disk recording on their lofty Synclavier II system. However, despite valiant attempts by pioneers like Wolfgang Palm and PPG's HDU (1986), hard disk recording took a backseat to less expensive tape options well into the 1990s.

By 1991, however, the first major strides had been made. Digidesign had released Pro Tools, a four-voice hard disk recording system. Assuming you could afford Digidesign's proprietary hardware, the Mac-based Pro Tools offered many of the features we now use every day: recording, mixing and even editing were available. By 1994 the available track count had reached 48.

By that time, similar systems had appeared for Windows users, most requiring some form of proprietary hardware interface. However, Steinberg had introduced a version of Cubase that could record eight tracks to an Atari Falcon 030 computer without any dedicated hardware, and the modern era of music production was set to begin.

8. VSTi

We might have rolled this one into the VST category, but we felt that the “instrument” incarnation of Steinberg's VST technology deserved its own mention.

We'd only just gotten used to the idea of native effects when Cubase 3.7 came out in 1999, carrying with it a brand-spanking new version of the VST format and an innocuous little plugin called Neon. Virtual instruments had, of course, been around for some time - Propellerhead's groundbreaking ReBirth, for example, had been out for a couple of years. However, this was the first time a virtual instrument had been so elegantly integrated into a plugin host. Even if the flimsy Neon wasn't anything to write home about, the promise of the VSTi format was clear.

Steinberg and third-party developers were quick to fulfill that promise. Steinberg's first commercial VSTi offering, the Model E, may have left analogue aficionados scratching their heads, but they soon hit it out of the park with a terrific virtual recreation of the famous PPG Wave 2.3. They weren't the only ones tempting our wallets or teasing our imaginations. Eventually, our plugins folders were bursting with free and commercial emulations, and originals of the sort that we'd never dreamed possible. And nary a cable in sight!

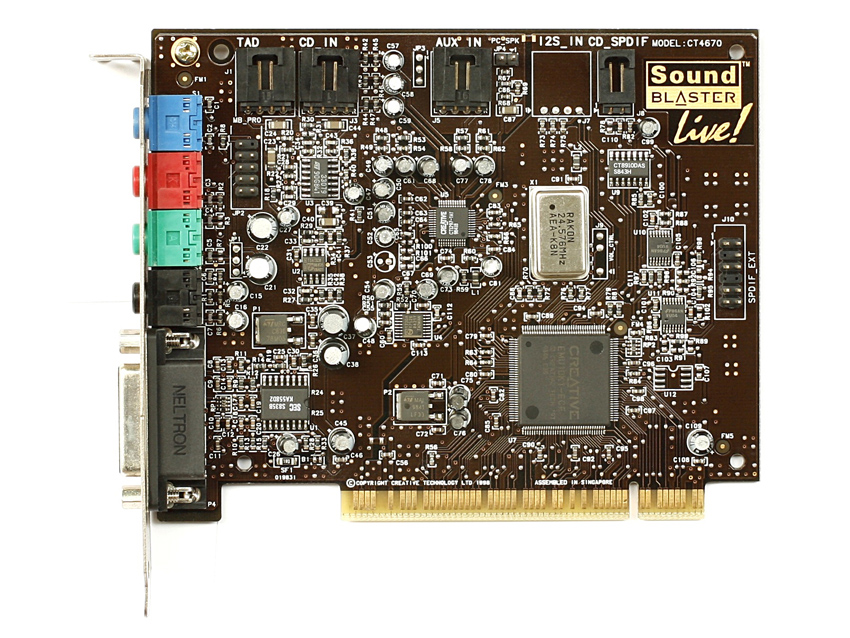

9. The soundcard

Recording audio into one's computer is a tantalising idea, particularly if one is not required to splash out on proprietary hardware to do so. This was the promise of native DAWs offered by Steinberg, Cakewalk, et al. The catch? Said audio is only as good as the audio interface used, and that excludes pretty much every computer's built-in soundcard.

Fortunately, computer hardware manufacturers have always included expansion, options and hardware manufacturers were quick to see a market. Initially, there was an obvious distinction between costly professional interfaces and those aimed at consumers (usually gamers). That distinction grew hazy when Creative Technology (AKA Creative Labs) released its Sound Blaster Live! PCI card in 1998. We're not going to pretend that the Sound Blaster offered truly pro quality, but it did provide a 48kHz sample rate and duplex recording/playback for a budget price that allowed many musicians their first taste of computer music production.

Eventually, low-cost options like M-Audio's Audiophile 2496 offered even better sound at a price anyone could afford.

10. The vacuum tube

The technology behind the vacuum tube was around for many years before Thomas Edison patented the 'Edison Effect'. In fact, Edison himself did not at the time wholly understand the physics involved, and it would be another 20 years before John Ambrose Fleming came up with his 'oscillation valve', essentially a rectifier or diode (meaning that any current passing through would be on a one-way journey).

Rectifying diodes were not terribly useful for amplification. That would come in the form of the triode tube, patented as the Audion by Lee DeForest in 1907. DeForest's invention allowed signals to be electronically amplified for the first time, and is widely considered the beginning of the electronic age.

Though tubes would eventually be replaced by smaller, cheaper, and more dependable solid-state components, vacuum tube-based microphones, amplifiers, filters and compressors are still very much sought-after and used. Many musicians and engineers insist that tube-based gear sounds better than solid-state designs.

Whether or not you agree, there's no denying that the invention of the vacuum tube irrevocably changed the way we make, record and listen to music.

11. The mixer

You probably know the name Studer, manufacturer of some of the finest tape machines ever to grace a recording studio. However, did you know that Studer was also behind what is widely regarded as the first commercially available mixer? Indeed, the Studer 69 was completed in 1958, though its release was stalled by some rather rigorous tests of the Swiss Postal Authority's Inspection Department.

Like the mixers that followed, the 'portable' Studer 69 was big, bulky and cumbersome. Yet the advent of multitrack recording made it a crucial part of the recording studio. In less than a decade, the mixer would grow into the massive, fader-and-knob-laden behemoth that would come to epitomise the recording studio in many a layperson's mind. Tube-based mixers gave way to sleek solid-state jobs in the late 1960s and those in turn would, for a time, be supplanted by digital consoles and, more recently, software variants.

Regardless of the technology under the hood, the mixer has become a creative tool in its own right, with the word “remix” now a part of our cultural lexicon.

12. The sampler

Analogue synthesizers ruled the electronic music scene throughout the 1970s but, as that decade wound to a close, musicians were looking for something new. It's hard to believe now, but analogue synths were, at that time, seen as old hat.

In 1979, an Australian company called Fairlight gave us all a glimpse into the next decade when it unleashed its Fairlight CMI, a digital sampling synthesizer. Initially meant as a digital synth called the Qasar M8, sampling was added at the eleventh hour when experiments with something akin to digital modeling synthesis proved too intense for the available processing power. The result was the Fairlight CMI I, the world's first commercially available polyphonic digital sampler.

To say that the Fairlight and successive samplers made an impact would be a vast understatement. Not only did sampling (and sample playback) overtake every other form of electronic sound generation, but it would eventually evolve into the very digital recording we take for granted today. Frankly, it's hard to imagine a world without samplers - and we wouldn't want to.

13. VST

We've seen a lot of technological advances in our time, but few can rival VST when it comes to computer music production.

It's hard to overstate the impact that the release of Cubase VST 3.02 had way back in '96. That specific iteration of Steinberg's DAW included a handful of plugin effects in the form of Chorus, Espacial, Stereo Echo and Auto-Panner. These weren't the first such plugins to be bundled with a DAW, but they were the first in a new plugin format that Steinberg dubbed Virtual Studio Technology, or VST.

VST differed from other formats in that Steinberg made the SDK (Software Development Kit) free for the asking. This allowed other developers to create compatible plugins and even incorporate VST effects into their own software. It blew the doors wide open. VST plugins started rolling out in droves, and many a budding software developer cut their teeth cobbling together plugins either for free or to put on sale. The smoke has yet to clear...

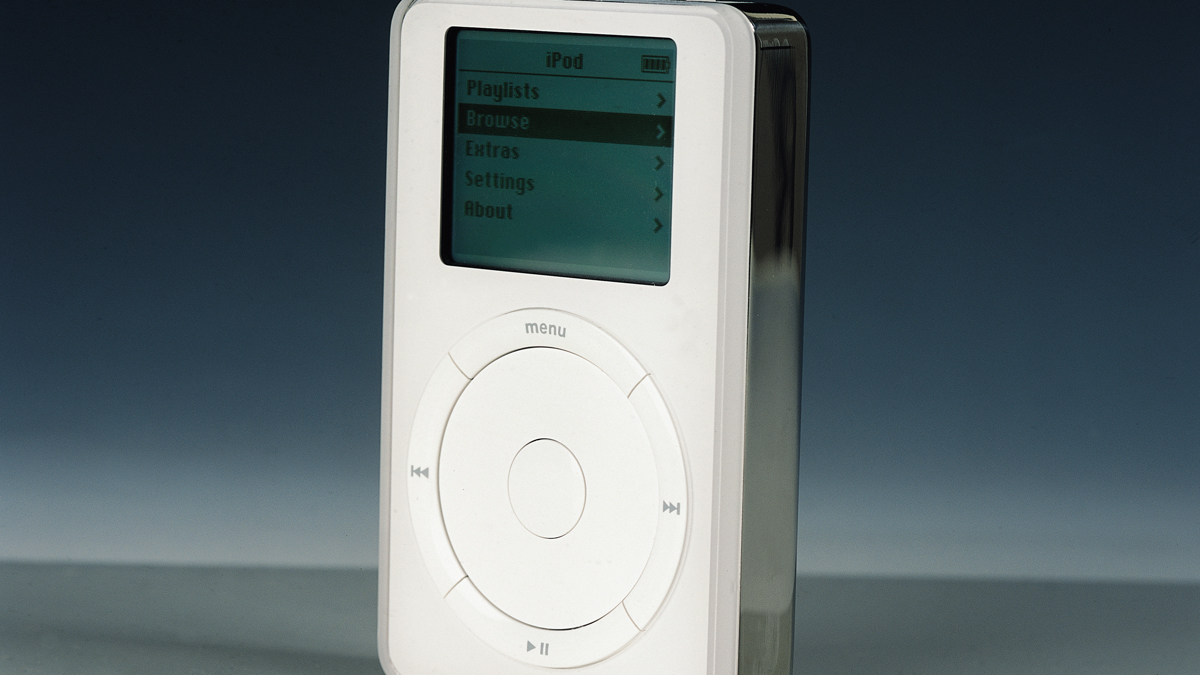

14. MP3/digital delivery

Some of us are old enough to remember the brief period of time when cassettes overtook vinyl as the delivery format of choice for music buyers. Sure, some tape formulas allowed hi-fi performance, but most commercial tapes were thin and noisy. Frankly, it made no sense at all, at least to those of us who had made it our life's work to eek every last drop of audio quality from our gear.

Yet there was no denying that the general public had other ideas. Portability was more important than fidelity to most listeners. Many of us old-timers had similar misgivings about the MP3 format when it arrived in 1995. Here again was a portable format that had at least a minor impact on fidelity.

As it turns out, sound quality was the least controversial aspect of the MP3 format. The very portability that made it so appealing has also threatened to topple the established music industry. So far, the industry has survived, but it has not come away unscathed.

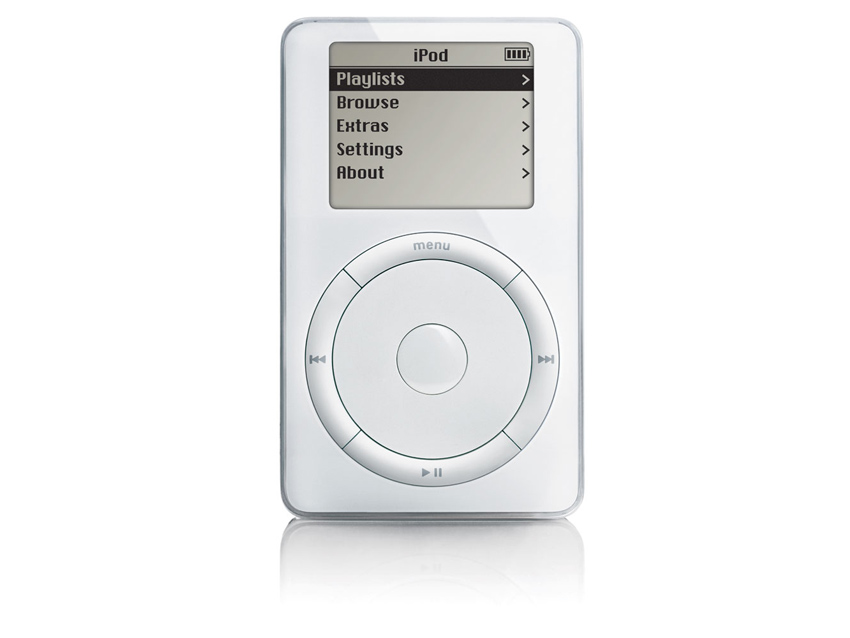

In the process, new methods of delivery and distribution have arisen, not least Apple's iTunes and iPod music player (2001). More importantly, it has allowed independent musicians access to legions of listeners without having to rely on record labels, distributors and retail stores. Music production has now truly been democratised, and this little compression algorithm was largely responsible.

15. Magnetic tape

A variety of methods for recording and playing back audio signals were in use before the advent of the tape recorder. Edison and Bell had both been producing variations on wax cylinder recording devices since 1877, and these cylinders reigned supreme before they were toppled by Emile Berliner's Gramophone disc recordings in 1910. Meanwhile, Danish inventor Vlademar Poulson was recording to magnetic wire.

All of these methods produced less than convincing results. This changed in 1928, when a German fellow named Fritz Pfleumer came up with the idea of coating a bit of paper tape with ferric oxide. This breakthrough formula was refined and sold by BASF, with AEG's Magnetophon K1 being the first successful tape machine.

Walter Weber's application of AC biasing was almost as important, improving the sound quality dramatically. For the first time, what was played back sounded nearly identical to what was recorded. So convincingly, in fact, that tape broadcasts by the Germans in WWII stumped the Allies, who couldn't figure out how a single announcer could be broadcasting from several different locations simultaneously. The age of high fidelity had begun.

16. The electric guitar

From lutes to lyres, banjos to balalaikas, stringed instruments have been with us for at least two millennia - the Harps of Ur were discovered back in 1929 in what was once ancient Mesopotamia and proved to be over 4,500 years old. It seems pickin' and strummin' is as old as civilisation.

Yet the stringed instrument was given an electrifying kick in the sound-hole in 1931, thanks to George Beauchamp, who spent much of the 1920s coming up with ways by which to electrify and amplify lap steel guitars, bass guitars and violins, to name but a few.

Eventually, he co-founded the Ro-Pat-In Corporation with Adolph Rickenbacker and Paul Barth, and later National Stringed Instruments Corporation and Rickenbacker Guitars. Ro-Pat-In included Beauchamp's electric lap steel guitar and electric guitar in catalogues going back to 1932, though Beauchamp's hollow-body electric guitar wasn't patented until 1936.

We needn't remind you of you the impact made by this singular instrument. Early adopters included Les Paul and T-Bone Walker, and it would come to epitomise rock 'n' roll, giving teenagers of the 20th century a voice of their own and spawning a host of musical heroes that belonged to specifically to their generation.

The electric guitar was and is far more than a musical instrument - it's an iconic symbol of modern (and youth) culture.

17. The synthesizer

By the early 1960s, popular music had become electrified. Musicians and listeners alike were looking for novel sounds. Producer Joe Meek and his Tornados used the Clavioline to interject a bit of space-age electronica into their 1962 hit Telstar, while television viewers thrilled to the eerie sounds of the BBC Radiophonic Workshop's Doctor Who theme a year later.

It was during this time that Americans Robert Moog and Donald Buchla were independently putting together what would be the first commercially available synthesizers. Buchla completed his modular instrument in 1963 and began selling it in 1966. However, Moog's instrument made the bigger splash thanks, in part, to the familiar organ-style keyboard that could be used to play it.

Released in 1964, Moog's modular system was used by artists as diverse as Gershon Kingsley, The Beatles and the Monkees, but it was Wendy Carlos's 1968 LP Switched On Bach that made Moog's name synonymous with the word “synthesizer”. A slew of exploitative electronic cover albums followed and, by the time the electrons had settled, Moog had put the synthesizer into the hands of gigging musicians with the Minimoog. Popular music would never be the same.

18. Multitrack tape recorder

Prior to the introduction of the multitrack tape recorder, studio engineers were limited to capturing a live performance as it happened, often recording multiple takes and settling on the best one.

The drawbacks of this approach are obvious. A brilliant band recording could be ruined by a single flawed performance. Additionally, the mix was written in stone (or ferric oxide, as it were).

Ross Snyder changed history when he developed the first 8-track tape recorder at Ampex in 1955, a unit promptly sold to guitarist Les Paul, who used it to record a number of groundbreaking releases. Used initially as a means to enhance vocals and other instruments with a new technique called 'overdubbing', Les Paul and his wife Mary Ford planted the seeds of an entirely new art form - the art of modern studio recording.

Thanks to multitrack tape, the studio was now a sonic playground. Without it, albums like The Beatles' Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band or Pink Floyd's The Dark Side of the Moon would never have been possible.

19. The native DAW

By the mid-'90s, ADAT and Pro Tools had put the tools to record digital audio into professional and project studios the world over. Yet most home recordists were still relegated to cassette multitrack machines.

Even though the price of an ADAT was far less than that of a similarly outfitted tape machine, it was still beyond the reach of many, and Pro Tools? Well beyond the average musician's budget. More importantly, neither of those options offered MIDI recording of any sort.

It would, in fact, be the developers behind MIDI sequencer software packages that would create the template for the modern DAW (Digital Audio Workstation). The now defunct Opcode, for example, added a few tracks of audio recording and playback to their Vision sequencer in 1990 - though using it required Digidesign's hardware. As mentioned in the HD recording entry, Steinberg managed to incorporate eight tracks of audio into Cubase Audio for the Atari Falcon 030, along with such niceties as DSP effects, all in 1993. Over 20 years ago, the template for the modern DAW was in place.

20. MIDI

Before 1983, interconnection between musical instruments made by one manufacturer and those made by another was a dicey proposition. Some synthesizers could, with a bit of work, talk to one another through the magic of voltage control and gates, but not every manufacturer could agree to a standard. A Minimoog had a different trigger system than did an ARP Odyssey, and neither used the same voltage scaling as, say, a Korg MS-20. Something needed to happen, and that something was MIDI.

An acronym for Musical Instrument Digital Interface, MIDI was designed as a standard protocol for data transmission, interfacing and hardware connection. Any MIDI-outfitted instrument can communicate with any other via a single cable. Initially, this meant little more than stacking synthesizers from different manufacturers for a layered sound, but soon MIDI would be used for interfacing with computers, controlling mixers and effects and even stage lighting.

Thanks to USB, Thunderbolt and other computer interconnectivity standards, the number of actual MIDI cables in the average home studio has diminished, but the technology is still being used every day, some three decades after it was introduced, and MIDI 2.0 is now a thing, too. That's nothing short of amazing.

21. The microphone

People were trying to amplify their voices from as early as 600 BC, and the first versions of the modern microphone appeared as early as 1860. However, the first documented microphone capable of transmitting anything like a reasonable signal came 17 years later.

Independently developed by Thomas Edison and Emile Berliner in the US and David Edward Hughes in England, the carbon microphone is the precursor to the microphones we use today. Hughes came up with the term 'microphone' to describe his invention, a device that used carbon granules behind a metal plate - the diaphragm. When sound waves struck this diaphragm, it varied the pressure on the carbon granules which, in turn, affected electrical current - current that could be transmitted down telephone lines.

Though Hughes had demonstrated his invention years earlier, Edison was awarded the patent - after a lengthy legal battle with the aforementioned Berliner.

The carbon mic would be used for nearly a century in telephones all over the world and gave rise to the development and refinement of the modern microphone, an ultra-sensitive instrument capable of capturing the subtlest nuances of voice or instrument.

“From a music production perspective, I really like a lot of what Equinox is capable of – it’s a shame it's priced for the post-production market”: iZotope Equinox review

"This is the amp that defined what electric guitar sounds like": Universal Audio releases its UAFX Woodrow '55 pedal as a plugin, putting an "American classic" in your DAW