Mike Oldfield: “It’s the age-old story. Out of suffering comes beauty”

When Oldfield’s world fell apart he found salvation through music that channelled the spirit of his '70s work

Introduction

When Oldfield’s world fell apart in 2012, he found salvation through a new album that channelled the spirit of his '70s work. “It’s the age-old story,” says the enigmatic writer of Return To Ommadawn. “Out of suffering comes beauty…”

A Skype video call with Mike Oldfield is liable to cause pangs of jealousy. It’s 10am in the Bahamas, and as the songwriter activates his webcam, the backdrop evokes a Bounty advert. Palm trees rustle in the balmy breeze. A carefree speedboat zips past on the bay.

Out of suffering comes beauty. It seems that somebody who’s content with life isn’t able to produce enough emotional power

Oldfield tinkers with the media command centre on the decking of his no-doubt-palatial home and considers his lot. “I am quite spoilt. There’s even a very well-stocked guitar shop just a mile from here. So if I ever need a lead or a new set of strings, it’s just down the road.”

Peer into his world and Oldfield seems every inch the serendipitous rock legend living in royalty-financed utopia. Don’t be fooled. The 63 year old is rightly proud of latest album, Return To Ommadawn, but these shiveringly beautiful instrumentals - much like those of its 1975 prequel, Ommadawn - were born of all the worst things that life can throw at a man. A long legal battle. The passing of his father. The death of his son at 33.

“It’s the age-old story,” he says, rolling a cigarette. “Out of suffering comes beauty. It seems that somebody who’s content with life isn’t able to produce enough emotional power. It has to be something that really makes your hair stand on end. The circumstances of the last four years reminded me of the situation I was in back in the 70s.”

That decade established Oldfield’s career-long pattern of alternating highs and lows. Having outgrown the Reading folk circuit, the young guitarist released an album with his sister, then played bass for psych-rock talisman Kevin Ayers, before hawking the demo of what became 1973’s Tubular Bells across an apathetic industry. Everyone passed, except a 22-year-old Richard Branson, who made it the inaugural release on Virgin Records.

“I always had a bit of a sixth sense,” Oldfield reflects of the two-part prog opus that would slow-burn to 17 million sales. “I took my little tape in and I didn’t understand it. Why couldn’t they see? Then fate made it possible, through Virgin, who actually allowed me to make it.”

Celtic grace

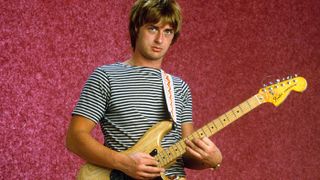

Aged just 19, the precocious multi-instrumentalist was all over the credits of Tubular Bells - overdubbing 20 instruments from glockenspiel to penny whistle - but his inimitable guitar touch was already the main event.

“When I listen back to Tubular Bells and Hergest Ridge [1974],” he says, “it sounds like yesterday. For a start, I use all five fingernails on my right hand, not a plectrum, so I get a very pure sound. That’s why people don’t seem to see me as a guitar player. When there’s a video of me, I don’t look like I’m doing very much.

I often slide down the fretboard at the end of a note, or stop the string with my right hand to give it that characteristic click

“I use Celtic grace notes a lot,” he adds. “I use violin vibrato; I can only think of Robert Fripp who also uses that. I often slide down the fretboard at the end of a note, or stop the string with my right hand to give it that characteristic click. And I often play one note with a lot of power to start a melody.”

Surprisingly, given the intricate multitracking of those first albums, the period saw Oldfield rely on just one electric guitar: a ’66 Telecaster, stripped of its Olympic White finish and decal, modified with a Bill Lawrence middle pickup and phase-reverse switch, and either DI’d or run through a Fender Twin Reverb during sessions at Oxfordshire’s Manor Studios.

“Everything was done with that Tele,” nods Oldfield. “When I started out with my sister, our agent also worked for Marc Bolan, who’d just got these very elaborate electric guitars made by Zemaitis… Our agent gave me this old white Tele; I was absolutely over the moon to have a proper electric guitar.

“That was the guitar all the way through Tubular Bells and Hergest Ridge,” he adds. “What I didn’t have in those days - not until Ommadawn - was the searing Gibson sound. I remember, some time in the mid- 70s, I had some money to spend. So I went to Denmark Street, paid a few hundred pounds and walked away the proud owner of a ’69 Gibson SG.”

Oldfield will humour enquiries about Tubular Bells and Hergest Ridge, but you sense he’d rather move you onto 1975’s Ommadawn, the third album he describes as “a genuine piece of music rather than production - hands, fingers and fingernails”.

Ommadawn breaks

As before, the format found two extended tracks sprawled over each side of the original vinyl, but this release was a musical departure, weaving a pastoral soundscape where Irish and African influences bled together and acoustic curios like bodhrán and mandolin were offset by the roar of P-90s.

“I had a particularly good Twin Reverb,” he recalls. “I wound up the input gain and instead of a solo, I’d just play one note, two notes on the SG - then stop. I’d never heard a guitarist do that before. Ommadawn was made in this little shack at the top of a hilltop looking over the Welsh mountains. It was windy up there and there were thunderstorms.”

Everybody jumped on the punk bandwagon. Progressive music was trashed. I had to sort of survive in that environment

The darkening weather was symbolic. As Ommadawn sessions began in January ’75, the phone rang with black news: Oldfield’s mother had committed suicide. The guitarist was unravelling. A naturally private man - at early folk shows, he recalls “trembling so badly that the guitar was jiggling up and down” - the mania of stardom had led him “halfway down the corridor to total madness”.

Yet he was in too deep to stop. “After Tubular Bells, Hergest Ridge and Ommadawn, there was tremendous pressure on me to make money for my record company. In the beginning, it was a one-artist label, then they got the opportunity to sign these… to me, they were just skinny guys shouting. But that was seen to be revolutionary, whatever that means.”

Do you mean the British punk movement? “Yeah, I think it was called that. The label did that to improve their image, really. And everybody jumped on the bandwagon. Progressive music was trashed. I had to sort of survive in that environment, and instead of clinging to my true self, I had to make music like everybody else made.”

Today, Oldfield is candid on the subject of his mid-period catalogue, admitting to “losing my way” as he soldiered through the decades. Yet there were still triumphs, not least hits such as 1983’s Moonlight Shadow, with its screaming electric lead and visceral rhythm track.

“It is fun thrashing an acoustic guitar,” he nods. “Moonlight Shadow was built around a very tough Ovation and I was absolutely thrashing it to hell. We had a fantastic drummer, Simon Phillips, and the hi-hat and the acoustic were locked together in that powerful backing track. Even though the vocals sounded quite folkie, the backing track was steaming.

“If I tried to get another guitarist to play that, they’d go [limp] jang-jang. The acoustic can sound decidedly wimpy. You’ve got to actually attack it. It took a lot of physical energy to play that hard.” Have you mellowed since then? “Not in my playing. Probably in my personality.”

Know thyself

Certainly, Oldfield seems more poised than the 40-something raver who could be spotted falling out of the clubs of Ibiza in the late 90s.

Five years ago, it even felt like he had attained elder statesman status, as a performance at Danny Boyle’s Olympic Games opening ceremony brought him to a global audience of 900 million and boosted his sales by 757 per cent overnight.

“That sort of validated me and everything I stood for. So that gave me confidence. There was only way to go,” he counters. “Down.”

It all boils down to who you are and what you’re feeling as a human being. That’s what comes out from the guitar

It feels crass to drill into the tragedies that prefaced Return To Ommadawn, but Oldfield readily admits he found catharsis through this material, just as he did with his 70s work.

“In the early days, I was able to externalise my emotions. There are parts of Tubular Bells that sound like heaven, with choirs and mandolins. With Ommadawn, too. With Return To Ommadawn, a similar thing has happened. It all boils down to who you are and what you’re feeling as a human being. That’s what comes out from the guitar. If you’re playing something because Eric Clapton did it, you’re not going to give much of yourself. It’s about connecting your playing with your innermost emotions.”

Return To Ommadawn revisits many of Oldfield’s calling cards. These two epic instrumentals slip gracefully between sounds and cultures, offering rousing choirs, tribal drums, manic flamenco rhythms and knife-through-butter electric lead. It takes time to compose these works, he says.

“An important thing for me are these new high-definition 4K computer screens, which let you see a whole piece of music in one lump, instead of scrolling. I start with an old clockwork metronome, then it’s basically just playing around.

“When I started this album,” he continues, “and I got the acoustics out, I found I could still play. The thing is, I learnt so young - I was already pretty good at 11 or 12 - that it’s part of my DNA.

“One problem was the hardness of my fingertips on my left hand. They’d gone all soft, so it hurts. Also, my muscles had gone a bit over the years. I’m into my 60s now. So I had to just work out on guitar for three weeks, get back into shape. But the technique was all still there.”

Return To Ommadawn

Unfortunately, the equipment wasn’t. Following “a strange period” postmillennium, he decided to clear his entire studio and record 2005’s Light + Shade entirely on computer software.

Seeking to recreate the sound of the original Ommadawn, Oldfield bought a mandolin, ukulele and bodhrán. For the bulk of the acoustic work, meanwhile, he picked out an Andy Manson Heron, with its jumbo format, bear-claw spruce top and flame maple body.

For the Spanish sections, I’ve had this Paco De Lucia signature for 20 years

“It’s lovely,” he says. “You know that a human being crafted this thing out of wood, by hand, after many years of experience. It hasn’t come out of some factory. For the Spanish sections, I’ve had this Paco De Lucia signature for 20 years. I didn’t want the Spanish [sections] to sound too good; I wanted them to sound spontaneous and human, leave the imperfections in there.”

As for his electric passages, Oldfield found himself hunting down old tools. “I found out recently that Gibson have remade the SG with the same pickups I used, the P-90s. It’s a very good recreation, almost better than the original. But it was still hard work. None of the plug-ins I could find sounded right. There’s no substitute, sometimes, for the real thing.

“The only thing that sounded similar to Ommadawn was a Boogie Mark Five: 35. For the lead guitar, I got the Gibson, plugged it in, wound up the input gain - and there it was. For some of the backing guitars, I used the Pro Tools Eleven Rack.

“Towards the end of Part Two,” he continues, “there’s a long section with just the Gibson, almost a cappella, playing little phrases of the melody. It’s almost like a Shakespearean actor reciting with great power and emotion, very slowly. To be able to able to play one note with power, then leave a great big hole without it being boring and meaningless is something that I feel we managed to achieve on this album.”

Organic sounds

Do you find your touch on electric is as assured now as it was then? “Luckily, I can still play,” says Oldfield. “I try to stretch myself. I wanted to put in adventurous chords, major 7ths and 6ths. But I’m maybe not as fast as I was.

“There was this very fast part in the original Ommadawn, and at one concert - it was like the band were out to get me. They started it off just about playable. Then they sped up, until the end, when I was like, ‘Argh, for God’s sake, give me a break!’ But I managed to get through it. I don’t think I could play that fast now.”

The music we have now, it’s like you’ve taken all the food that was ever consumed in the world and condensed it into this porridge that everybody eats

For better and worse, times change. 42 years after Ommadawn, Oldfield is aware this sequel will emerge into a markedly different music scene.

“When all the synths and sequencers started coming out in the 80s,” he sighs, “it was all very exciting and I thought it would lead somewhere. Where it’s led is that we’ve now got artificial intelligence music - you’re simply pushing a combination of buttons. You can create perfect music, but it all sounds the same. I can tell when a computer has made something perfect and it really turns me off.

“The music we have now,” he continues, “it’s good, but it’s like you’ve taken all the food that was ever consumed in the world and condensed it into this porridge that everybody eats. There’s nothing special about it. There’s nothing wrong with it, but things have got to have flaws. That’s why I left a lot of the imperfections in Return To Ommadawn. There’s bits where I missed a note, or it’s a bit out of time or tune. It doesn’t matter. What’s important is that the music has power, soul and spirit. It’s alive.”

In the age of the instant-gratification earworm, no realist would expect Return To Ommadawn to rival Tubular Bells for cold, hard sales. Oldfield shrugs. This album has delivered on his vision, achieved a musical rebirth and drawn a line under his darkest days.

“If I tried to make something commercial, it would have been a disaster. This album is my true self. It’s interesting to find that same person is still there. He just needed to be switched on again…”

Return To Ommadawn is the sequel to 1975’s Ommadawn and is available now on Virgin EMI

"I'm like, I'm freaked out right now. I'm scared. I feel like I'm drowning on stage and I feel like I'm failing”: SZA on that misfiring Glastonbury headline set

“It sounded so amazing that people said to me, ‘I can hear the bass’, which usually they don’t say to me very often”: U2 bassist Adam Clayton contrasts the live audio mix in the Las Vegas Sphere to “these sports buildings that sound terrible”

"I'm like, I'm freaked out right now. I'm scared. I feel like I'm drowning on stage and I feel like I'm failing”: SZA on that misfiring Glastonbury headline set

“It sounded so amazing that people said to me, ‘I can hear the bass’, which usually they don’t say to me very often”: U2 bassist Adam Clayton contrasts the live audio mix in the Las Vegas Sphere to “these sports buildings that sound terrible”

Most Popular