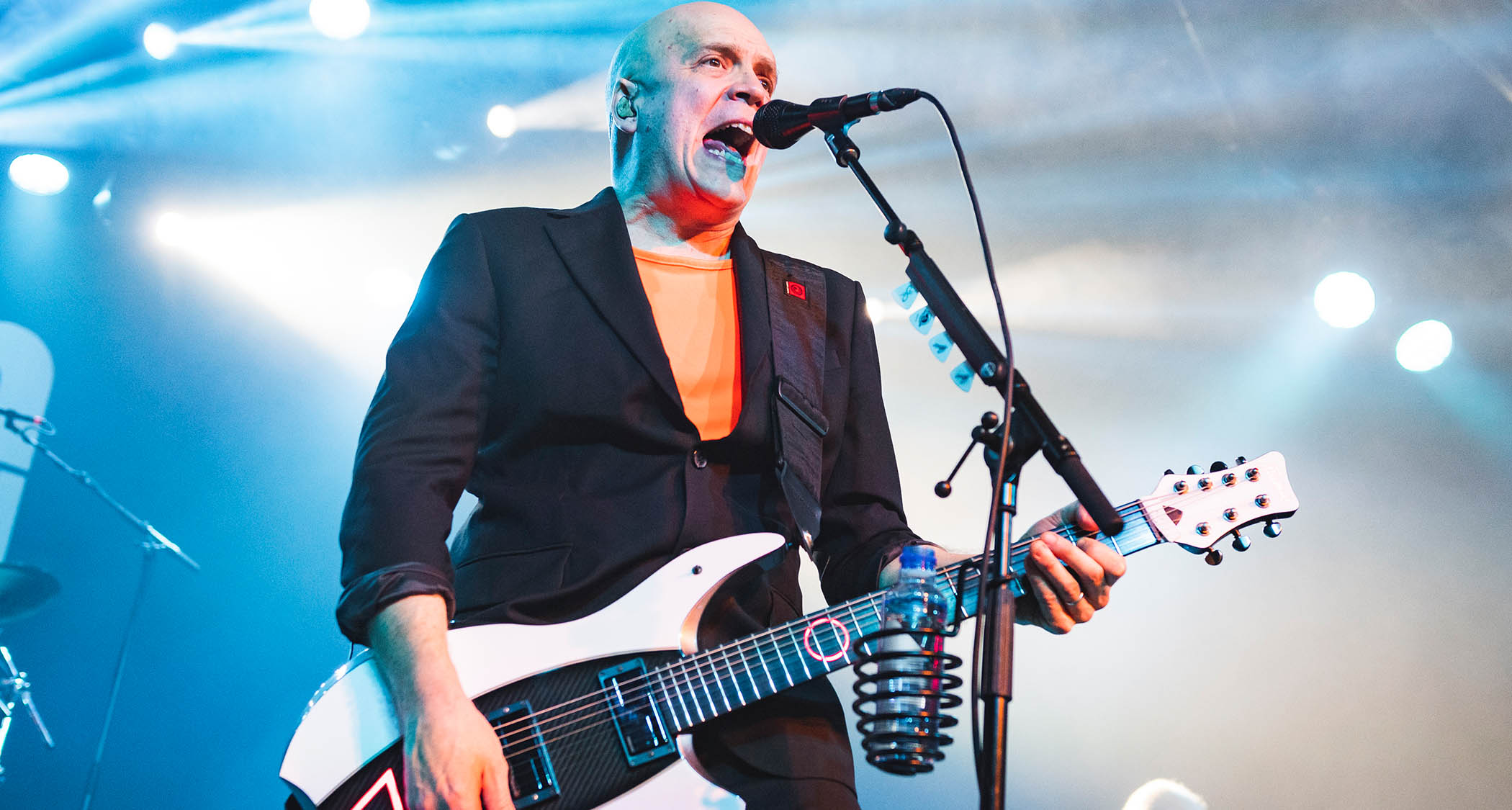

Steven Wilson discusses The Raven That Refused To Sing (And Other Stories) track-by-track

“I think I've become a better storyteller over the years," Steven Wilson says, discussing the fullness of feeling and mad passions that run throughout his forthcoming solo album, his third, titled The Raven That Refused To Sing (And Other Stories). “There’s an overall theme that runs through the record, which is each piece being a self-contained ghost or supernatural story. But like all great books of short stories, all of them together make a cohesive piece."

Other powerful, recurring elements that inform the album's six epic, bravura tracks are the fear of mortality and end-of-life regret. Wilson admits that such subject matter is rough, dark stuff, but he stresses that the message, along with the sound of the songs, is ultimately reassuring. "We all share these feelings," he says. "Nobody is alone in these thoughts."

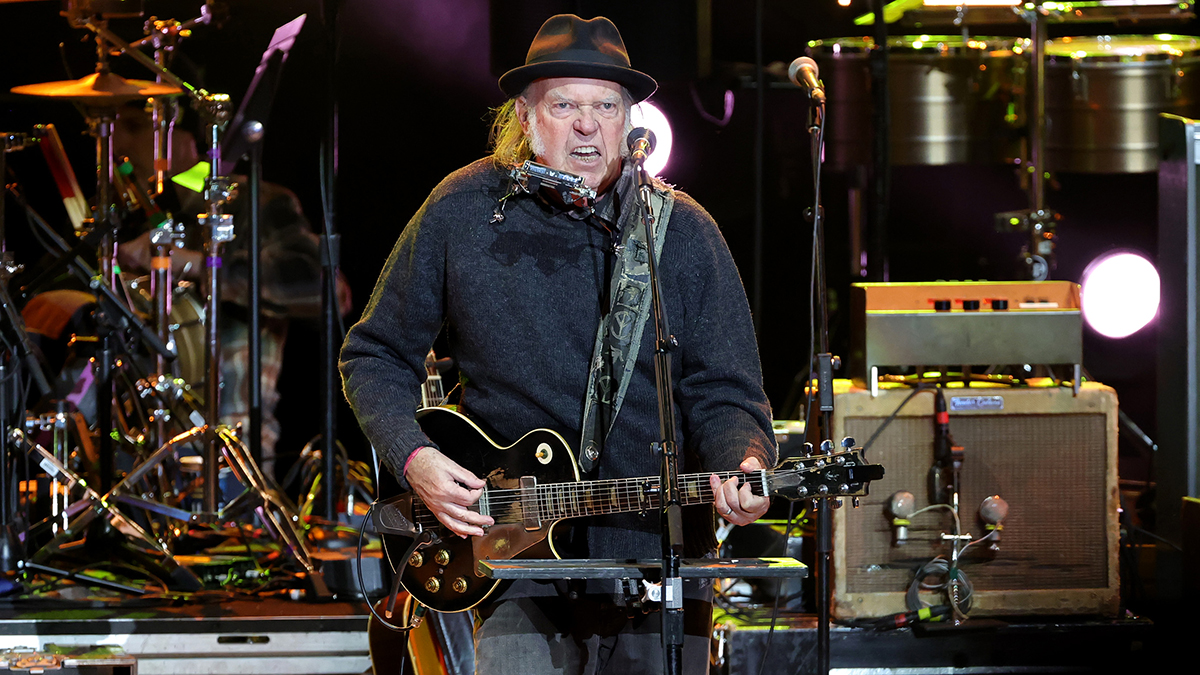

Because of the expansive song length that has become a hallmark of much of his work, particularly as the singer, guitarist and frontman of Porcupine Tree, along with his celebrated remasters of albums by King Crimson and Emerson, Lake & Palmer, Wilson has often been called a "progressive" artist – a term he is not entirely comfortable with. Labels aside, he sees himself as having tremendous freedom in not being bound by the conventions of the three-minute song.

“It's incredibly liberating," he says. "At the same time, it’s hard to get it right, because the minute you throw away the rulebook on how you structure a song, you risk falling flat on your face, which I’ve probably done over the years with some of my long pieces. But I think I’ve gotten better at it."

The manner in which Wilson recorded The Raven That Refused To Sing differed dramatically from his previous solo efforts (2008's Insurgentes and 2011's Grace For Drowning) in that he cut tracks live in their entirety with his recent touring band (Marco Minnemann, drums; Nick Beggs, bass; Adam Holzman, keyboards; and Theo Travis, flute, saxes and clarinet; guitarist Guthrie Govan, who played in the studio, is a new recruit).

“It was scary yet fun," Wilson enthuses. "Scary in that I was actually making a record where I couldn’t control every aspect of the performance, but exciting and easy because I had faith in the band. These guys are constantly blowing my mind. The compositions were written for this particular lineup, so I was consciously giving them stuff that I knew they were going to have fun with – including myself.

Wilson produced and mixed the album, but as he was operating as something of a "musical director" for the band, he knew he needed an ace engineer. He got that, but he got something else, too – a legend. "Alan Parsons was was top of my list," Wilson says. "He’s made fantastic records with The Beatles and on his own, and he recorded what is, for many people, the best-sounding record that has ever been made, which is Dark Side Of The Moon. I'm so glad that I was able to do this album with him."

Songs were tracked in three or four takes, and while everything from amps to keyboards to EQs was analog, the final data capture was digital, which Wilson says afforded him enormous liberties for editing. "We didn't cut things up like a lot of people do nowadays," he says. "But I could take elements of one take and put it in another. It could be a solo from one take that was put onto another. That's a great way to work."

As a scrupulously crafted, brilliantly sustained emotional experience, The Raven That Refused To Sing succeeds massively. But the most marvelous and thrilling thing about it (and the most surprising) is how it comes together inside your head once it's over. Repeated listenings reveal new subtleties and meanings. Wilson, ever the southpaw, doesn't deal in easy, straightforward advances; he creeps up on you invisibly, unhurriedly, ultimately invading your soul.

On the following pages, Steven Wilson discusses The Raven That Refused To Sing (And Other Stories) track-by-track. “The record was made with a lot of passion and commitment, and a great sense of joy, too," he says. "One of the great ironies about this kind of music is that lyrically it’s quite dark; the music is melancholic, very aggressive almost atonal; but it’s a very, very beautiful and uplifting album."

You can pre-order The Raven That Refused To Sing (And Other Stories) at StevenWilsonHQ.com. The album will be released 25 February.

Luminol

“This is a story about a street musician, a busker. It was inspired by a guy who plays in my local town. He’s there every single day. It doesn’t matter what the weather is like; he’s always there, playing his acoustic guitar and singing these songs. Snow, rain, gale force wind – nothing will stop him from being in his spot.

“And the thing is, he’s terrible, absolutely rubbish. He never seems to get any better, no matter how much he plays these songs. I’m one of many people who pass him every day; he’s part of the street furniture, in a way. I suddenly started thinking, What would happen – God forbid – if he dropped dead in the middle of the street one day? Would people notice that he was no longer there?

“Then I had another thought: He’s the kind of guy who is so set in his routine that even death wouldn’t stop him. So I had this vision that he would drop dead one day, but the next day he’d be back in the same spot, playing the same songs, just like he always did. This kind of idea that somebody could be a ghost in life, as well as a ghost in death, somebody who’s completely ignored even in their lifetime – it hardly makes a difference; and death doesn’t make a difference, either; it doesn’t break the routine. That’s the story behind Luminol.

"It was the first piece I wrote with these musical personalities in mind. We did play it live on the second part of the Grace For Drowning tour, kind of as an experiment to see how it would fit with everybody, and also to see how the audience would react. That all worked out very well.

“Going into the studio with Luminol was a good was to ease us into the recording process. It went down incredibly quickly, and it was an opportunity to test the whole scenario, the idea of doing it live with Alan recording. We didn’t have to worry too much about the piece itself since we all knew it pretty well.

“Musically, you can break the song down into many parts: riffs, harmonies, melodies, rhythms. There is a strong, exciting opening part and then the song section in the middle, and then there’s the big Mellotron part straight after. After that is the recapitulation of the opening.

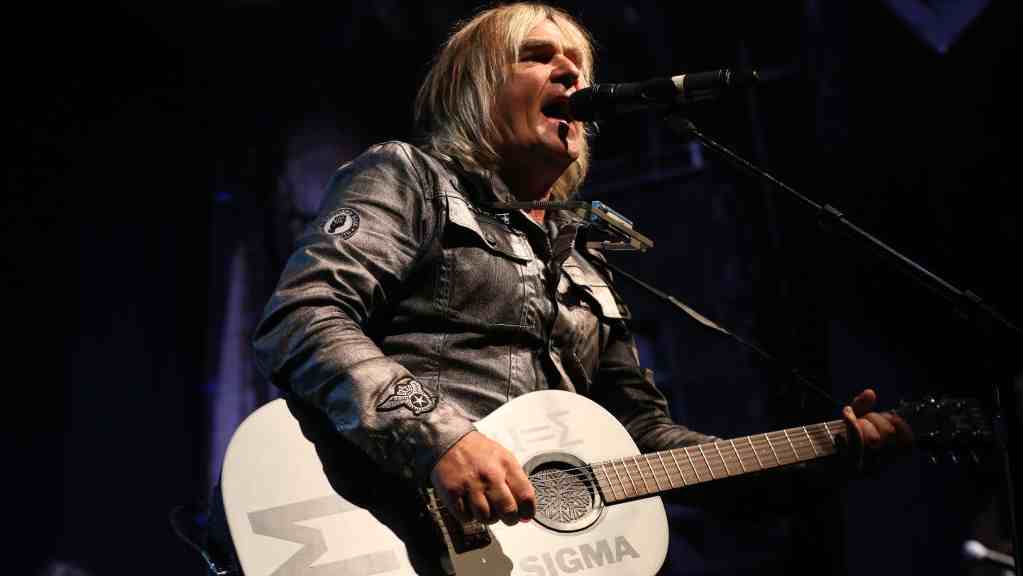

“There were some things that changed in the recording, but we didn’t really change it too much from the way we played it live. Guthrie was new; he hadn’t played it before. But I didn’t play much guitar. Once you get Guthrie in the band, you take a step back and say, ‘OK, there’s no point in me trying to take solos now.’”

Drive Home

“The song is based on a story but one that wasn’t mine; it was suggested to me by the guy [Hajo Mueller] who was illustrating, doing the artwork and the book. The idea is about a couple driving along in a car at night, very much in love; the guy is driving, and his partner – his wife or girlfriend or whoever she is – is in the passenger seat, and the next minute she’s gone.

“The guy is crazy: What happened? Where did she go? He does all the obvious things: looks under the seats, stops and checks the road, all of that. The song is basically about missing time; it’s the idea of blocking out time because of something so traumatic that you literally remove it from your mind.

“The story ultimately winds up with the ghost of the partner coming back, years later, and saying, ‘I’m going to remind you now what happened that night.’ There was a terrible car accident, and she died, etcetera, etcetera – again, the idea of trauma leading to a missing part of this guy’s life. He can’t deal with the reality of what happened, so he blocks it out – like taking a piece of tape and editing a big chunk out of it. It’s a sad, very beautiful song about loss.

“It has an extraordinary guitar solo. Guthrie’s playing is just sublime. That, for me, is the memory of this song. I had done a solo on the demo, knowing that I wanted an anthemic, epic solo at the end. In the studio, we did four or five takes, and each time Guthrie would reinvent the idea of what the solo could be.

“The particular solo we chose was either the first or the second one. It was so inspired and had such a beautiful sense of logic and storytelling to it. It’s one take, unedited, and it’s just unbelievably brilliant. And it’s improvised – he didn’t plan anything. It was such a moving experience to hear him play it. I was almost in tears."

The Holy Drinker

“This one is kind of tongue in cheek. It’s basically about a guy who’s very pious, very religious, preachy and self-righteous. I’m thinking of TV evangelist-types – guys who are prepared to tell people that they’re living their lives wrong and that they’re missing something because they don’t believe in God or whatever it is.

“He’s also an alcoholic, by the way – the typical scenario. He’ll tell you that your life sucks and that you’re bad, that you have all these vices, and meanwhile he has plenty of his own.

“One day, he’s in a bar and he challenges the stranger next to him to a drinking competition – without realizing that this person is the Devil. Of course, you can’t beat the Devil at a drinking competition – you can’t beat the Devil at anything – and so he loses. The great irony is that he’s vindicated, in a sense, but in the worst possible way. He gets dragged to Hell.

“It’s kind of funny, but the music is quite dark. It starts off with a three-minute instrumental section before the vocal comes in, and that initial part is a pretty furious rush of energy. I believe I was thinking of Mahavishnu Orchestra when I wrote it.

“A lovely Moog solo by Adam, kind of classic Jan Hammer-style, and lots of dirty keyboard sounds. I love the very end section, which is very evil sounding. People think it’s a guitar, but it’s a Fender Rhodes put through a distorted amp.

“A lot of these songs have different motifs that crop up, and I like that. One of the hallmarks of bad progressive rock, if we can use that term – I’m fairly ambivalent about it – is that it’s simply a bunch of sections strung together that don’t really belong. This idea of giving gravity and weight by stringing bits together, that’s easy. I could get a bunch of ideas that are half-formed, put them all together into a 20-minute epic, and say, ‘Now I’m an artist.’

“A lot of bad progressive rock, particularly modern, neo-progressive rock, sounds like that to me. It’s like they couldn’t write a decent song, so they just came up with a lot of half ideas and put them together to make them sound substantial. It doesn’t work with me. What I like to do is have these sections flower from the same musical source.”

The Pin Drop

“In some ways, it’s one of the simplest pieces on the record, but it was also the hardest to get right. It’s all about the dynamics and sustained sense of tension and release. There’s really only one or two musical motifs in it, so it’s all about the way it’s layered and structured. We did the most takes of this song than any other.

“Lyrically, it’s one of two songs, consecutively on the record, about marriages or relationships gone wrong – The Watchmaker being the other one. They’re both songs about the idea of inertia or spaces within marriage; it's the concept that you can be with someone because it’s comfortable and convenient, not because there’s any love or empathy.

“The song is basically sung by the wife. She’s dead, she’s been thrown in the river by the husband, and she’s floating down in the river while singing this song – from beyond death, beyond the grave, as it were. It’s quite macabre.

“The idea is that sometimes in a relationship there can be so much tension, so much unspoken resentment and hatred, that the tiniest thing can set off a violent episode, and in this case, one that ends in tragedy. The sound of a pin dropping on a floor can be the thing that instigates the fury.

“With this band, I’ve been able to concentrate more on being a singer. I tried something a bit different: I opened up my throat and sang in a less contained, less controlled way. I was very inspired by a singer called Nick Harper – he's the son of Roy Harper. They both sing in a dramatic way that I love. I was thinking of Nick when I did the vocals.

“Guthrie plays another extraordinary solo towards the end. This time we fed it through a Leslie cabinet. I’m a big fan of Leslies. A lot of people associate them with the past, but I think it’s a timeless sound. I’ll put anything through a Leslie – guitars, keyboards, vocals. It’s such a wonderfully rich sound.”

The Watchmaker

“Another adventure. This is the story of the watchmaker, the guy who is meticulous about his craft, but he never has any kind of emotional outburst, nor does he express violence or any extreme emotions whatsoever.

“It’s the idea of a couple who have been together for 50 years or more, purely because it was convenient and comfortable. There’s a line that says something like ‘You were just meant to be temporary while I waited for gold.’ So it’s the idea that they got together almost because they didn’t want to be in a situation where they weren’t dating somebody, and they’ve ended up together for 50 years, even though there was never a strong feeling of love between them.

“If you allow yourself, life can pass you by. Time is tick, tick, ticking away. If you’re not careful, you can find that your whole life has gone by, with this idea of ‘Maybe I’ll do this one day...’ It’s a very sad sentiment of regret, of what should have been and what could have been. Sometimes that feeling of comfort can be a real drug.

“The watchmaker ends up killing his wife and burying her under the floorboards of his workshop. But, of course, she comes back, because she’s been with him for 50 years; she’s not going to leave him now. So again, it’s the idea of death not making any difference in a situation. You can kill me, chop me up, bury me, but I’m still not leaving.

“At the very end, it’s very dark, and the wife comes back to take him with her, which is another classic ghost story, in a way.

“Musically, the beginning section is very much inspired by the way Genesis used acoustic guitars early in their career. I was never a big fan of Genesis; I never listened to them as a kid. But I’ve started listening to them more recently because I’m good friends with Steve Hackett. One thing I love about their early records is the chiming quality of the 12-string acoustic guitars. That became the inspiration for starting off The Watchmaker.

“I like the idea of intertwining harmony vocals, two or three lines that work in a counterpunctual way. It’s something I learned from guys like Brian Wilson but also Crosby, Stills & Nash and Todd Rundgren – anyone who has fabulous, multi-part harmonies.

“We got some great bass sounds on the album, thanks to Alan. There’s kind of a bass solo on this song, but it’s one that I wrote out and planned meticulously. In the past, there haven’t been a lot of opportunities for me to explore that. In my solo work, however, I’ve backed off heavy guitar stuff, which has opened up all of this space for things like keyboards and woodwinds but also this big, upfront lead bass sound. Think Geddy Lee or Chris Squire of John Entwistle.”

The Raven That Refused To Sing

“It’s a very simple song, again about loss and mortality. I think it would be hard for anyone to write about mortality without it being, to some degree, personal.

“Whether we like to admit it to ourselves or not, we’re all obsessed with mortality. And we should be, because we know that one day we’re going to cease to exist. We’re going to die. It’s the one thing that all human beings have in common. And possibly, we are the only species on earth that are aware of our own impending mortality. That’s such a heavy burden to carry around with you; it does affect everything in life.

“It’s about an old man at the end of his life who is waiting to die. He thinks back to a time in his childhood when he was incredibly close to his older sister. She was everything to him, and he was everything to her. Unfortunately, she died when they were both very young. This is not autobiographical; it’s fiction in that respect. But the guy is now at the end of his life, and he’s never been able to form any other kind of relationships. He’s spent his entire life alone, unable to relate to any other human beings.

“A raven begins to visit this man’s garden, and the raven begins to represent a symbol or a manifestation of his sister. The thing is, his sister would sing to him whenever he was afraid or insecure, and it was a calming influence on him. In his ignorance, he decides that if he can get the raven to sing to him, it will be the final proof that this is, in fact, his sister who has come back to take him with her to the next life.

“One of the things about my lyrics is, I try to be simple. I do it with the music, too. I don’t like things to be complex, intellectual or obtuse just for the sake of it. I love the simplicity of certain phrases. What’s special about being to say ‘I love you,’ but in a new way… it’s so hard to do that. They’re such clichés, in a way. Being afraid to love someone, being in love with someone… if you can find a way to make these things sound fresh again, that’s a really special thing to do.

“The one worry I had with all of the guys but particularly with Guthrie, my new guitar player – because Guthrie is such an extraordinary guitar player; he’s one of these guys who can shred and play a lot of notes. He can wipe the floor with so many guys. I turned to him with this song and said, ‘Are you OK with this? I’m only asking you to play two or three notes.’ I thought it might be dull for him. And he said, ‘No, I love doing it, because they’re the right three notes, and it’s the right thing to play for the song.’ That, to me, was a very profound thing for him to say.

“If you give people something where the simplicity is the way to go, and it’s all about the feeling… It’s about breaking your heart with one note rather than appealing to your intellect with a thousand notes. They love it! Guthrie was having a great time playing these notes, because he felt that it was the right thing for this piece of music.

“The biggest thing is to make people feel. It’s easy to appeal to the intellect. I could go and write some silly, complicated shit, but the hardest thing is to hit somebody’s heart and soul. I want spirituality rather than technicality.”

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.

"With her on it, it got three times better": Watch Billy Idol and Avril Lavigne perform their new single, 77

“I was shocked. That was the exact sound that I had been chasing for years”: Nirvana tone sleuth Aaron Rash solves his epic tone mystery and finds the guitar that Kurt Cobain used for In Utero

"With her on it, it got three times better": Watch Billy Idol and Avril Lavigne perform their new single, 77

“I was shocked. That was the exact sound that I had been chasing for years”: Nirvana tone sleuth Aaron Rash solves his epic tone mystery and finds the guitar that Kurt Cobain used for In Utero

![Epiphone goes high-end with its Inspired By Gibson Custom 2025 collection: [from left] the '63 Firebird in Polaris White is joined by a 1959 Les Paul Standard, a '64 SG Standard, a 1960 Les Paul Special in TV Yellow and a 1962 ES-335 reissue.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/3N4uVp3ezzrrhjCbY8KNfn.jpg)

![YouTuber Aaron Rash [left] wears grey and an Adidas beanie and checked trousers as he poses with his Veleno-clone aluminium guitar. On the right, Kurt Cobain performs in 1993 with Nirvana at their MTV Live and Loud show in Seattle.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/aqcaqZZK7FsRFWvoMPzMF9.jpg)