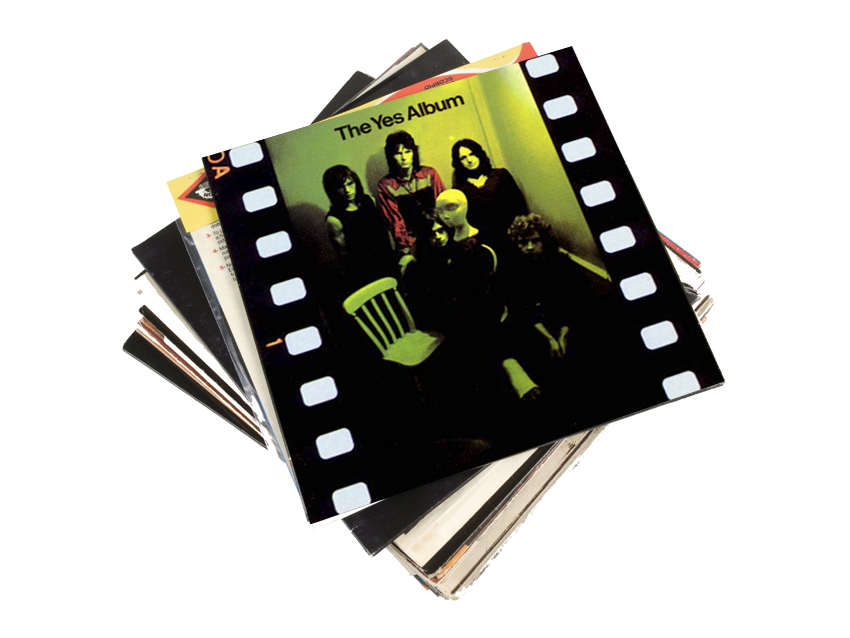

Steve Howe talks The Yes Album track-by-track

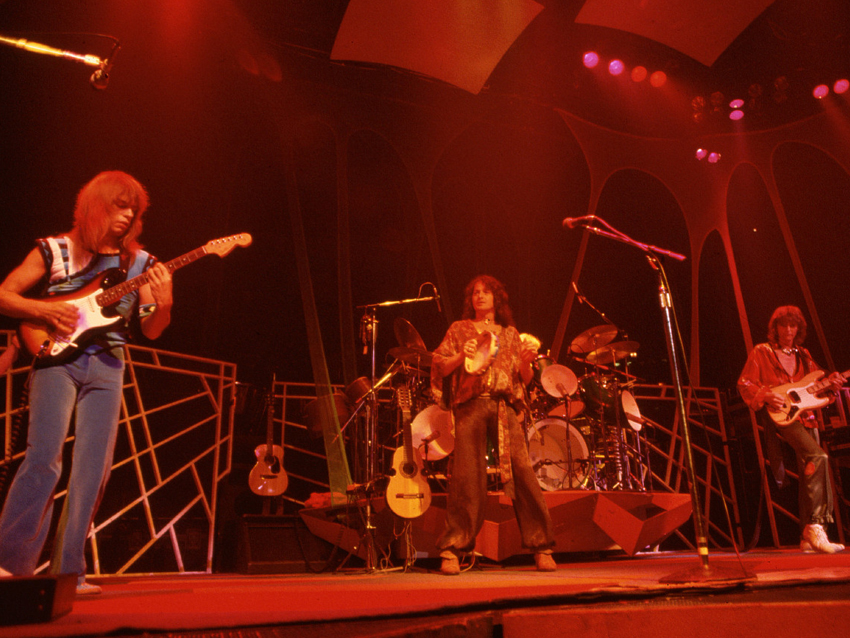

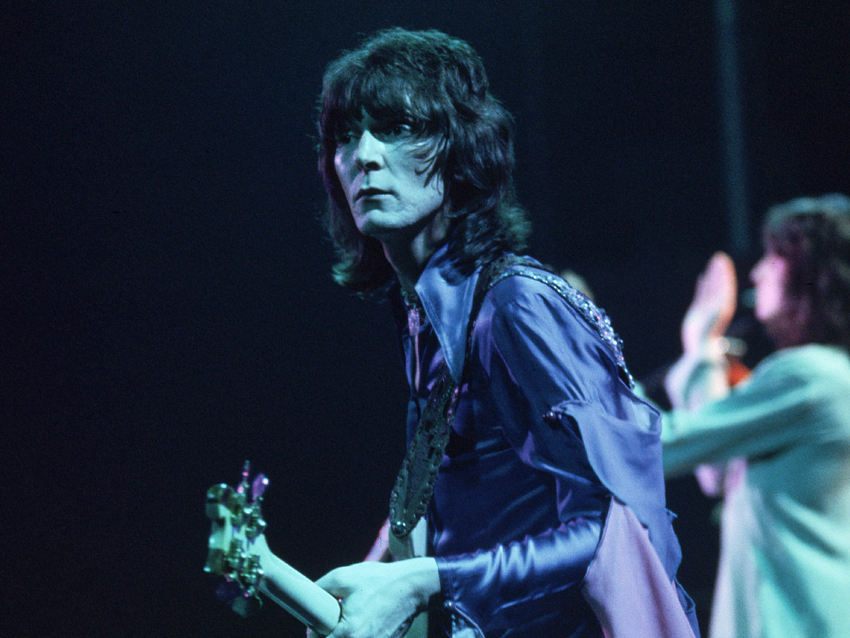

“We were certainly cocky and chirpy," says guitarist Steve Howe, recalling the late months of 1970 when he, singer Jon Anderson, bassist Chris Squire, keyboardist Tony Kaye and drummer Bill Bruford recorded Yes' third long-player, which was simply called The Yes Album. "There was a feeling of confidence in the room that we were doing something ambitious and fresh."

It would be Howe's first record with the band (he had replaced Yes' previous guitarist Peter Banks), and he remembers that he had no trouble at all fitting in immediately. “I’d been playing well, doing things in various bands," he says, "but I needed something that would move the air. When I got in with Yes, I said, ‘This feels good. We’re all equals, and everybody’s outstanding.’ It was like joining an orchestra, where all of the members are of a very high level. I thought, We’re going to do something pretty great."

The group worked up material, mostly at a farmhouse in Devonshire, England, before heading to Advision Studios where they tracked with producer-engineer Eddy Offord. Many of the songs were long (two of them come in at over nine minutes a piece), and as Howe sees it, they set a standard that Yes would follow on future discs.

“We weren’t going to be obvious and predictable," he says. "We didn't want to do three-minute songs for the radio, although we did manage to get a lot of radio play. Bill loved to play challenging music – I don’t think he was very used to 4/4 time, in fact. And I was one of those people who dug in and said, ‘I’m not going to play blues.’ We had a lot of musical integrity and held tightly to our ideals."

Much like Emerson, Lake & Palmer, who also recorded at Advison and would compete with Yes for studio time there, the band had total freedom to create – no pesky A&R guys lurked about asking for hit singles. "But it wasn’t like we were just jamming with no point," Howe says. "Everything had to matter. You had to play parts; you had to know what you were doing."

As for being deemed 'prog,' the guitarist says that he didn't hear the term until years later. "Prog has a certain stigma to it – flared trousers and grandiose indulgence," he says. "Yes were more of a feet-on-the-floor band. We knew we were quality, and we thought, There’s no way people won’t buy what we’re doing, because we’re too good.” [Laughs]

Released on 19 February 1971, The Yes Album made a big splash on both sides of the Atlantic, hitting No. 4 on the UK Albums Chart and No. 40 on the Billboard 200 in the US. Starting 1 March 2013, Yes will play the album in its entirety, along with other classics, Close To The Edge and Going For The One, on tour in the US.

"I came up with the idea that we should play an album in full," says Howe, "and then it went to two and eventually to three. Certain venues will only allow us to play for an hour and a half, in which case we'll play The Yes Album and Close To The Edge. For the places that let us play as long as we like, we'll do all three. It's going to be a great night, and I can't wait to explore all of this exceptional music live."

On the following pages, Howe looks back at the writing and recording of The Yes Album, a record that he says came about because the band operated as "five like-minded people. Bill thought I was a bit of a hippie, so was everybody. We loved music, and we thought that was the key to survival in the universe."

Yours Is No Disgrace

“It’s quite an exceptional song, isn’t it? It’s big. We started with a percussive idea. There was a television program that had this opening – the ‘da-da-da-da’ thing – and we just changed the chords and moved everything around. It was slightly kinky, really. Our idea was orchestral: We’re going to start with something, and then we’re going to play a theme, then we’re going to stop, then we’re going to sing, and then we’re going to play more music. [Laughs]

“Bits came up as they were needed. We wanted to take our time and flesh out this idea where everybody could contribute the same kind of balance. I brought in guitar structures and stylized them around the possibilities that we had as instrumentalists.

“I played two guitars on it – my Gibson ES175D from 1964 and my Martin OO-18, which came from 1953. The fact that I didn’t have a lot of guitars didn’t really matter, because those two offered me a lot of beautiful sounds and options.

“There is a basic rhythm track I did with the Gibson. We recorded the song in sections. We weren’t going to just go in and play the whole thing for 10 minutes, but there is a lot of group playing and not a whole lot of individual things.

There’s some great effects and things for the ear. You’ve got the panning of the guitar, the wah-wah which goes into the acoustic and then into spacey guitar sounds and the jazzy stuff. I’m just a crazy, mixed-up guitar player, so I won’t just make one sound – I’ll do them all.

“Jon had written some lyrics with his friend David Foster, a Scotsman. So that’s what came in when we started singing, ‘Yesterday a morning came, a smile upon your face.’ I must say, Jon was brilliant at what he was doing, which helped bring about an enlightenment that we were now going to be making music that people wanted to listen to.”

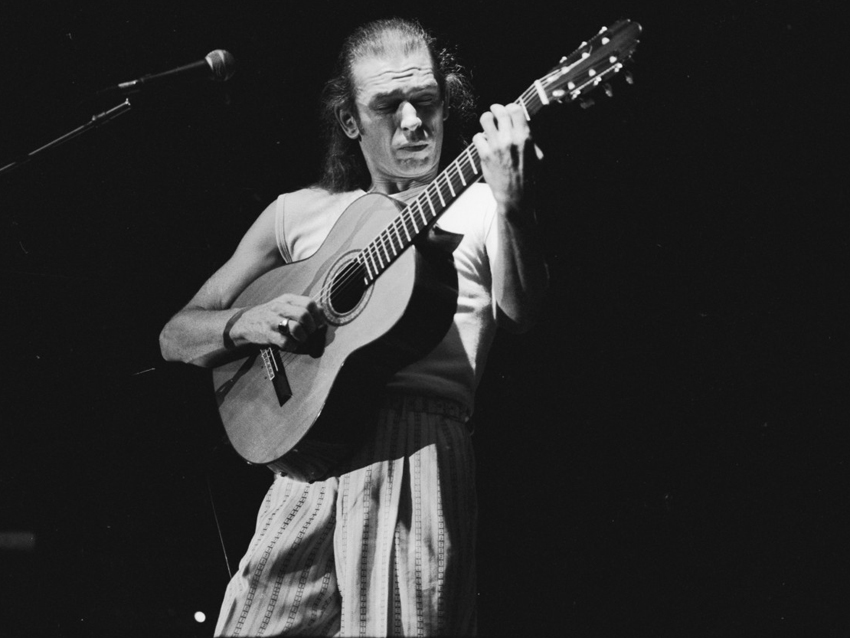

Clap

“I was so happy that Yes were open to having this type of song on the album, but I didn’t have a title. Jon said, ‘Why don’t you call it Clap?’ And I said, ‘That’s great – Clap.’ It was so simple and innocent.

“We recorded it live with Eddy Offord [at the Lyceum Theatre in London]. He used a Revox A77 going at 15 i.p.s. on quarter-inch tape. I think he put up a couple of really good mics up, but I’m not sure what they were. The only problem with the song was when Jon mis-announced it on stage and called it ‘The Clap,’ when it’s really just called ‘Clap.’ On the new CDs it’s written out correctly, but on the old albums it’s called ‘The Clap.’

“It’s the first song I ever wrote, and I think it’s really a good piece. I wrote it on the 4th of August in 1969, when my oldest son, Dylan, was born. The very night that he was born, I finished the song. Originally, it was a dedication to Chet Atkins, but then it became a dedication to Dylan.

“It combined a lot of things I’d learned or imagined. I always wanted to write music, and when I decided to write solo guitar music, it was earth-shattering inside, because suddenly I was an independent person. I could stand up on stage and play Clap. That meant as much to me as it did to be in Yes."

Starship Trooper

“We started with a good guitar sound, but it wasn’t what exactly we wanted to hear. So we sat down with a Bell flanger, and we basically put the whole track through it. It gave everything a lot of movement.

“The song wasn’t rehearsed; it was constructed in the studio from various pieces. I had the Wurm part from another band I used to be in called Bodast. It was in a song called The Ghost Of Nether Street. We’d recorded an album, but the label closed down, and so the record never came out.

“I always loved the section as a whole piece of music, so I decided to carry it over to Yes. I like the way it goes from G to E-flat to C, but different things happen on the roots. Although it repeats endlessly, it sometimes has the fifth below roots on the chords. It sounds like a lot going on, and of course, it’s flanged.

“The build-up of it is very impressive. It splits into two guitar tracks, one side taking a solo. Somehow, we did a bunch of takes, and so we’d pick the best of each. They were all done as complete takes. I remember thinking that I was sort of jamming with myself.

“The rest of the song is wonderful too. Jon had some fantastic writing on it. It’s arranged nicely. We did very little overdubbing, really.”

I've Seen All Good People

“We had the song pretty much worked up in rehearsals. The beginning of it, the parts where I’m playing the acoustic, they never sounded right, however, and so when we got in the studio, we got a click out and I played to it. I did a whole take that way. The click was Bill’s idea. What he’s playing with Chris, that ‘ba-doot’ beat, we made a loop of that.

“The guitar I’m using on the opening is a Portuguese 12-string tuned to a unique way that I think sounds right. The rock section does have a bit of a Western swing to it. That guitar solo is great – I wish I could keep writing them like that. It’s very much like a Bill Haley-type solo. When I played it, I believe I was thinking about how I liked that beboppy guitar approach. It sort of softens the rock but edges up the swing.

“I remember at one point saying that we needed some recorders, which everybody liked the idea of. A guy [Colin Goldring] came in and played them, and they sounded fantastic. I’m not sure if the organ is a Hammond or an actual church organ, but it rises up and it’s just incredible.

“When we do the song live on tour now, we’re going to move the keys down for the ‘I’ve seen all good people’ harmonies at the end. We do love to sing. In Yes, we’ve always had so many ideas for the various instruments, our sonic story, but the vocals are always a lot of fun to do too.”

A Venture

“This one definitely came up in the studio. I have that jazzy guitar part, and there’s the tinkly piano – lots of great stuff in the song. Tony was such a terrific player for me to work with because he was so comfortable supporting me and helping me, but he would find his moments too.

“I’ve always liked it. We’ve tried it on stage in different guises. In the early years, we used to jam on it a lot and make it quite complicated – just massive things happening. But now we’re determined to do a very good version of it live and make it as close to the record as we possibly can.”

Perpetual Change

“This is a song that really echoes the feelings of the Devon countryside where we were rehearsing. Jon was looking out at the scenery, and he just said, ‘There it is – perpetual change.’

“I just worked on the song with Geoff Downes, and when we looked at it, we realized that there’s only a few structures to it, but they come in different ways and with different irregularities, and they come together in a battle in the middle.

“How we started on the song was, we started on the fragility of ‘I see the cold mist in the night and watch the hills roll out of sight,’ and we build, getting some nice, jazzy chords in there. But returning as we do to the intro, it’s kind of very anthemic. Of course, it’s rocky too. We were doing it all very well. Then the monster bit happens in the middle. It’s going to be good fun playing the song on stage soon.

“I played the ES-175 on this as well – it’s on Good People, Disgrace, Starship Trooper and A Venture – but at the end of this song, I played an Antoria. Or it might have been a Guyetone. It was definitely one of the two. They looked the same. One was a copy of the other one, but I never really worked out which came first.

“The song is joyful, and it ends the album on such a nice note. Once again, it gives people the signal that Yes can be kind of classical.”

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.