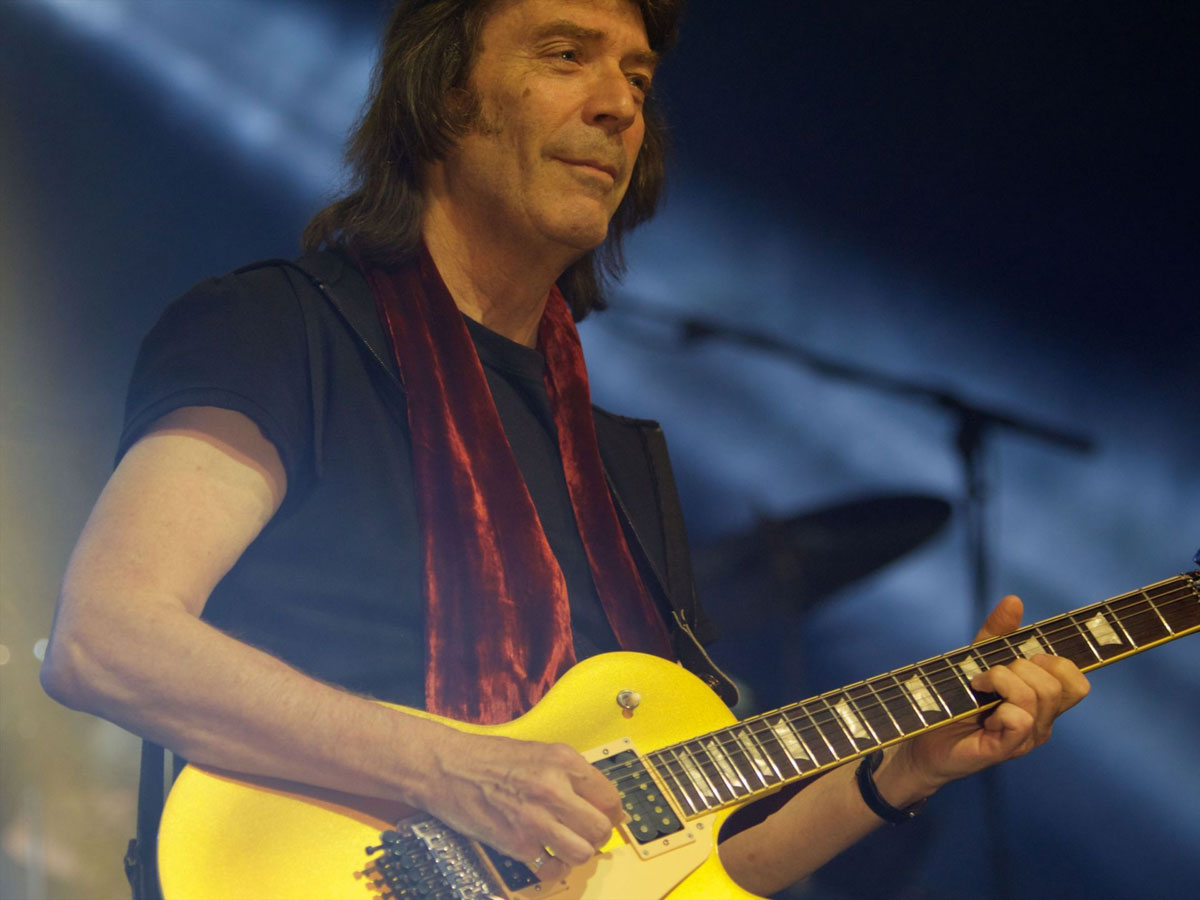

Steve Hackett talks Wolflight, phrasing and the nylon knack

The ex-Genesis genius on his new album

Introduction

As the lead guitarist in UK prog legends Genesis, Steve Hackett's pioneering style and technique was hugely influential on a whole generation of guitar virtuosos, from Brian May and Steve Rothery, to Edward Van Halen and Alex Lifeson. Now he's back with a hugely impressive new solo album, Wolflight, which proves once again that Hackett is the leader of the pack...

"Steve Hackett has long been regarded as one of the UK's most innovative and influential guitar players"

Steve Hackett has long been regarded as one of the UK's most innovative and influential guitar players. The prog rock legend - who spent seven years as lead guitarist in Genesis between 1970 and 1977 - is even widely credited with inventing two-handed tapping and introducing sweep picking to rock 'n' roll electric guitar. Hats off.

Hackett recently released his 23rd solo album, Wolflight - four decades since his debut solo record, Voyage Of The Acolyte - and it is arguably one of his most ambitious works to date featuring a "tag team" of metal, progressive rock, folk and blues with classical orchestral arrangements and music from across the globe, all gelled together with stories and residuals from centuries of the world's cultural history.

Indeed, the central theme for the new record is the fight for freedom, whether this be the struggles of Afro-Americans in the Deep South or the fierce battles of nomadic horsemen long ago in Asia.

As ever, Steve's guitar playing never strays from the sublime, whether he's plugging in an electric, picking at one of his beloved nylon six-strings or even trying his hand at an Arabian lute. Wolflight sees a more primal side to the musician (and not just on its cover artwork); it's a joy to behold...

Primal guitar playing

Wolflight not only espouses a central theme of freedom across its 10 tracks, but there is also a definite sense of musical freedom in terms of genres explored, your own diverse playing and the record's overriding primal energy...

"I'm hugely proud of this album - it's what I've been trying to do for a very long time"

"It's interesting that you discern it as primal energy, because that puts it in a different category, I think, to a lot of the other albums that I've done. I think my writing has been getting steadily more primal and slightly more elemental and a tad more Slavic, and all things belonging to Norse regions have been part of it.

"There's the odd borrowed harmony from Grieg or Tchaikovsky, and those guys from cold climates - people who were able to inform the orchestra as one instrument.

"They call classical music that tells a story ‘program music', but of course, in rock we call music that tells a story ‘progressive'. There's a correlation there somewhere with all of that.

"I'm hugely proud of this album - it's what I've been trying to do for a very long time, but I didn't necessarily have the means and the platform.

"It's not the kind of album that could have been done in the 80s, because at that time you could fall foul of record company politics by doing exactly what you wanted to do. The 70s was more of an era of doing exactly what you wanted, but I think now we're at that time again."

The musical box

You have mentioned previously that this album breaks the rules in many ways. Could you elaborate on that?

"Yeah, the way I think this album has broken the rules is because it works a bit like a relay team. You have these different genres or setups where each is a relay team or tag team where one takes over from the other.

"Great ideas sometimes come at five o'clock in the morning, which is wolflight time!"

"You've got the team that play rock and then you've got the team that do folk and then you've got the team that do world music and you've got the team that do the classical orchestral stuff.

"They're all different schools of thought, they all work in different ways and I wondered if it was possible to keep interrupting each team with something new, like if you stopped the rock band for a minute and suddenly had an orchestra doing a few bars.

"The danger is that you don't pull it off because it might just sound frumpy for a bit, but if it ends up coming across with the right amount of severity, it can be as incisive - I think - as rock."

How much of this album was actually composed on guitar?

"Most of it's written on acoustic, but then some of it's written in the imagination. Obviously, I do get ideas when I'm playing a guitar and that might come out when I'm playing electric at home or at soundcheck or practising in the dressing room.

"Those are good times for coming up with ideas when I'm not expecting to get anything out of myself. But then great ideas sometimes come at five o'clock in the morning, which is wolflight time!

"That's the time when you're not fully awake, which is a good thing, because you're in an altered state and you're just coming to, and so you can have certain odd perceptions."

The genesis of a solo

Do your solos tend to be written out or more improvised?

"I tend to improvise them as I go along but certain phrases - and I might think of those as voice phrases - can be written. It's a mixture sometimes.

"In Genesis, I was always writing solos. There were a few improvised ones, but there were not that many, because there was always such an emphasis on writing with the Genesis team. It is hard to move away completely.

"We can use all the technology available to enhance things, but essentially the performance has got to be there and it's got to be passionate"

"I think I probably erred more on the side of blues than any of the other guys in the band. I did always have the ability to be able to go into a blues... and I still do.

"I'm grateful to blues for that, because I think of it as non-harmony and chord-dependent. It's something you can share on stage with somebody else's band and I often have, where I don't know the tune but I just wing it as a blues player. It's stood me in very good stead."

As ever, your lead playing on the album features some wonderful phrasing. Could you explain your approach to forming such eloquent phrasing?

"I think the approach is really refined jamming. In terms of phrases, I stop and start a lot when I'm recording, no matter what I'm playing. It's a lovely feeling if I get a take all in one and it does sometimes happen, but the process is one of dealing with error in a way.

"I'll try it roughly and decide it's roughly right, but then realise it would be better if the tuning was something else or the tone could be slightly better or the timing could be better.

"We can use all the technology available to enhance things, but essentially the performance has got to be there and it's got to be passionate. If there's any secret to my phrasing and what's driven me the whole time, it has been the passion for it and that doesn't go away.

"I have to get the right sound for a start, and if I get that it will be inspiring. Some days, I'll get the perfect sound and think, ‘I can go anywhere with this sound - it's so wonderful!'"

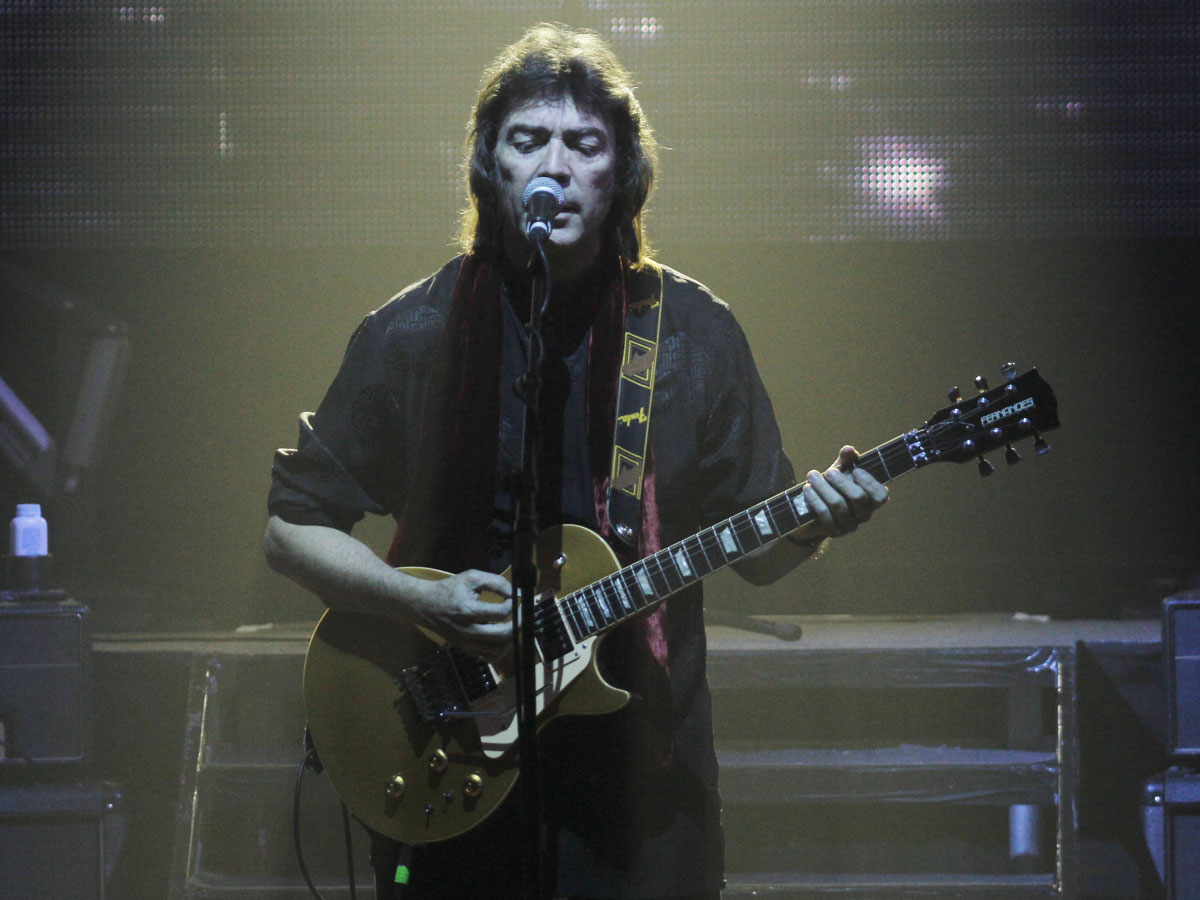

Funnelling the Fernandes

Did the Fernandes electric with the Sustainer pickup play a prominent part on Wolflight?

"Yes. On the album, it's a mixture of the Burny model Fernandes with the Sustainer pickup, which has the addition of a Floyd Rose tremolo, and my old 1957 Les Paul. They're both beautiful things and they're both great guitars.

"We can always find a happy compromise. Electric guitars are all about compromise, I think."

"I have never actually found an electric guitar that did it all - funny that, isn't it? There are just certain tones that I can get with the Les Paul and there are certain tones that I can only get with the other one.

"On record, I have been known to switch between them seamlessly in the middle of a single solo. Perhaps I'm after a thick cut from the Les Paul or maybe something that's very driven by upper harmonics.

"I wouldn't say either had the superior tone. They've both got different properties and they're both magic. If the Fernandes has a drawback, I would say that it doesn't have as much roll off at the top as I would ideally like because the Sustainer pickup interferes with that.

"If I want to get a very mellow tone, then I've got to use a wah with it or I have to set it in a certain way so it's not too bright. We can always find a happy compromise. Electric guitars are all about compromise, I think."

What approach to amplification did you take during the recording sessions?

"Well, live I use two 50-watt Marshalls, but in recent years, I've been going straight into the computer and I've been surprised at the amount of weight and cut that I can get doing that.

"I'd like to get a combo again though, because you always find that you're going back to basics"

"You know, I can still get it sounding like a beast spitting fire in the corner of the room! I've used various modelling devices, but one of the most recent ones was an Orange virtual amp, which sounded wonderful.

"I've actually just been doing a guitar workshop thing in Paris and they provided a Marshall combo, which I believe was 50 watts with a single 4x12 cabinet in it and it was one of those amps you plug into and just go, ‘Wow, great sound!' I've been meaning to get one and that may well colour how I record in the future.

"But one of the nice things about going straight into the computer is there's no tyranny of volume. The sound is not volume dependent, whereas for centuries guitarists have been dependent on cranking up loud.

"I'd like to get a combo again though, because you always find that you're going back to basics, and you know, how basic is using just a Marshall combo? It's almost back to John Mayall and the Bluesbreakers, isn't it?"

Acoustic acquisitions

As always, there's some incredible acoustic technique across this album. Which acoustics did you pick up and play?

"In the main, I used the Yairi nylons, which are Japanese. I've got one that's the loudest nylon guitar I've ever heard and so it does sound a bit like a piano. That's the one that you'll mostly hear on Wolflight.

"I use a Fishman Aura acoustic modelling device, which makes it sound like it's mic'd up"

"When I'm working live, I tend to use a cutaway and the sound is not dependent on the body and projection as much as the pickup and how it's treated live. I use a Fishman Aura acoustic modelling device, which makes it sound like it's mic'd up even though it's a pickup.

"I also played a Tony Zemaitis 12-string guitar on there. There are one or two other models of 12-strings on the album - a Farida and a Gibson - but that's the main one.

"I sometimes use the Farida live and I use the Zemaitis live, too. In recent years, it's been fitted it with a bridge pickup and it hasn't destroyed the sound. It's a very good beautiful, balanced-sounding guitar."

Nylon knack

The nylon guitars ring with such clarity and rich tone. How were they recorded?

"With nylon guitar, I sometimes seek out a piano tone, but it's always been so hard to translate that to record. But after years of searching for it, we used some subtractive EQ on this album to back off the top and back off the bottom so you get the sweeter area in the middle. We then tried to use reverb that wasn't too toppy and I'm really happy with what we've discovered and the results we've got.

"Recording nylon, any slight rustle can ruin it. It's like photographing fairies' wings in a gale!"

"I did an album called Tribute some years ago [2008], and it was essentially the most demanding stuff to play and record. I remember that Roger King [recording engineer, keys player and co-songwriter] had done some spectrum analysis on some Segovia stuff overnight, on tracks recorded in the 20s and the 30s.

"He played it back to me with some processing on top of it and I said, ‘Yes, that's the sound that I've been looking for!' - this non-bright lugubrious tone that minimises finger squeaks but still has this solidity when you're playing brightly up at the bridge. I'd been searching for these sounds all my life.

"Whenever you're recording nylon, any slight rustle or sound of breathing can ruin it. It's like photographing fairies' wings in a gale!"

Do you think your acoustic work has been overshadowed by your electric playing?

"Actually, I think it's probably the acoustic guitar that got me the job in Genesis in the first place! Even if I hadn't have been able to play a note of electric, I think they would have hired me anyway on the basis of the acoustic stuff, because we shared a love of the 12-string and six-string steel.

"Nylon really came later for me, from about 1973 onwards. I certainly became more involved with nylon and it started to creep in more and more. I was determined to try and get an aspect of nylon into rock, because it is the least rock 'n' roll of all the guitar options... and I think I achieved that!"