Session king/producer Danny Kortchmar looks back on 12 career-defining records

During the 1970s and into the first part of the '80s, it seemed as though Southern California had a lock on hit records. The Left Coast, which had ceded a sizable chunk of the '60s to British hitmakers, came alive with the deeply personal, meditative sounds of James Taylor, Carole King, Jackson Browne and other similarly introspective troubadours who connected with the masses and summed up the post-Vietnam era zeitgeist.

“It did feel like the center of the universe," says guitarist Danny Kortchmar, whose robust, rock and blues-infused licks and highly intuitive way of interpreting material made him the era's first-call picker among the period's A-list stars. "All hell had broken loose, and we were on fire," Kortchmar says. "We were cutting records all the time, every day. LA was the place to be back then, just like London in the 1960s. There was tons of work, tons of studios, musicians everywhere – you couldn’t throw a rock without hitting a genius."

Despite his hit-filled resume, Kortchmar says that he never intended on being a session player. In the mid-'60s, the native New Yorker hoped to find stardom as a member of such groups as The Kingbees and The Flying Machine (the latter of which included the then-unknown James Taylor). “I wanted to be in a band, but I also wanted to be in something like Booker T and the MGs or the Motown crew," says Kortchmar. "I always admired those guys who went into the studio all day long and cut hits, one after the other. So I was torn as to which direction I should take."

When The Kingbees broke up in 1967, Taylor headed to London to try his luck as a solo artist. Kortchmar had already hipped his friend Peter Asher, ex- of the duo Peter & Gordon and now running The Beatles' newly formed Apple Records, to Tayor's talents, and Asher quickly signed the singer to the label. Kortchmar stayed in New York City, playing for a time with the psychedelic rock band The Fugs. Around this time, an LA-based group called Clear Light came to town in search of a guitarist. Kortchmar quickly landed the gig and made the easy decision to relocate to California. "I said, ‘Sure, I’ll go out there,’" Kortchmar recalls. "New York was freezing cold, and there were no gigs, so I didn’t think twice about it."

Kortchmar's worked with Clear Light for the next six months until they disbanded. He then reunited with one of his ex-Fugs mates, bassist Charlie Larkey, along with another Manhattan friend, noted Brill Building songwriter Carole King. With King on vocals and piano, the trio formed The City and cut a record with producer Lou Adler called Now That Everything's Been Said. "That was the first full album I played on," Kortchmar says. "It was my real introduction to big-time LA recording work. I felt immediately comfortable in the studio, even though I was learning as I went."

The record failed to hit and The City called it quits, but soon after, when King cut her second solo album, Tapestry, one which would prove to be an unqualified breakthrough, Kortchmar and Larkey were aboard as part of the singer's studio backing band. At the same time, Kortchmar had reconnected with his old pal Taylor, now transplanted to LA himself, who was about to record his Warner Bros. debut, Sweet Baby James, with Asher producing.

The guitarist joined Taylor in the studio, along with a group of musicians that would soon loom large in his life, bassist Leland Sklar and drummer Russ Kunkel. “Once I started playing with Russ and Lee, I just wanted to be in the studio all the time, playing with those guys and cutting records," says Kortchmar. "My focus changed. Russ and Lee and I knew one another’s playing so well, it’s like we developed three-way telepathy."

The three established a tight bond, one which continued further with the addition of keyboardist Craig Doerge. When they weren't recording, the four musicians hit the road with Taylor, who nicknamed them The Section. "We’d be on tour with James, and after he finished his soundcheck, we kept jamming until they threw us off the stage," says Kortchmar. "But by playing so much, in the studio and out on tour, we really got to know what each guy was going to do in any kind of musical situation."

For Kortchmar and The Section, the work (and the hits) continued throughout the '70s. On many dates, Kortchmar found himself rubbing shoulders and trading licks with a shaggy-haired wild-card guitarist, fellow New Yorker Robert "Waddy" Wachtel. At first, Wachtel regarded Kortchmar as the enemy, but any perceived animosity fell away during their first encounter during a Lou Adler-produced date for a Tim Curry record. "I took one look at Waddy and said, ‘I love this guy,' remembers Kortchmar. "'He looks like a muppet – he’s gotta be great.’ We fell into it right away. One of the things we had in common was reggae – we’re both major reggae fanatics. With rock ‘n’ roll, we came at it with slightly different points of view, but once we started playing together, it all clicked."

For the majority of sessions, Kortchmar – or "Kootch," as he was affectionately called – relied on a Fender Telecaster Thinline he had bought in 1968. He brought the guitar to Red Rhodes' guitar repair shop on Cahuenga Boulevard, where Jeff "Skunk" Baxter, who would go on to fame in the Doobie Brothers, came up with a pickup and circuitry configuration that would prove invaluable. "I had three pickups – a Telecaster, a Stratocaster and a humbucker – and I could turn them on and off and put them out-of-phase, as well," says Kortchmar. "Jeff gave the guitar a wide variety of sounds. I put the Tele through an old Fender Deluxe. That was my go-to setup for a long, long time.”

As the '70s drew to a close, tastes changed – punk and new wave became the order of the day, although Kortchmar participated memorably on Linda Ronstadt's new wave-flavored 1980 release, Mad Love – and Kortchmar found new life as a co-producer, co-writer and musical foil for ex-Eagle Don Henley. "I did want to produce because it was like, ‘How fun is this? You get to hang out in the studio with your pals and create something?’" Kortchmar remembers. "Plus, I knew I’d be good at it because I was taught by the best – Lou Adler, Peter Asher, Carole King. I had a good idea of how to make a record. I was a good arranger, and I hired all the best guys, so I felt ready by the time I fell into it."

On the following pages, Kortchmar looks back on 12 of his most notable recordings. (Lead photo credit: Elissa Kline. Visit Elissa Kline Photography on Facebook.)

James Taylor - Sweet Baby James (1970)

“After The Flying Machine broke up, James fled to North Carolina, which is where his family was, and then to London. I gave him Peter Asher’s number and address. Peter and I were friends because my first band, the Kingbees, backed up Peter and Gordon on one of their first American tours. James hooked up with Peter, who signed him to Apple Records. They made an album, James’ first album – I wasn’t on that one.

“The way I approached the songs on Sweet Baby James was pretty instinctive. Of course, James is no slouch on the guitar himself – he’s a beautiful player. Peter was going for minimalism, and he wanted it to be as acoustic as possible. Fire And Rain has no electric guitar on it. That’s how Russ Kunkel came up with playing with brushes; he had to tone things down to fit with the acoustic guitar.

“It was a little like walking on eggshells. This was before they made acoustic guitars with pickups in them. It was a real lesson in subtlety and minimalism. I didn’t realize it was the start of something or that James was going to be on the cover of Time magazine. I knew he was great, but by this point I was already slightly cynical in that being great wasn’t always a guarantee that you would be a hit. I thought it should be, of course.”

Carole King - Tapestry (1971)

“The first actual album I played on was for a band called The City, which was Carole, Charlie Larkey and myself. At that time, Carole didn’t want to be a solo artist; she wanted to be in a band. We made an album called Now That Everything’s Been Said, which Lou Adler produced. Jim Gordon played drums. It’s a great record, but it came and went.

“The next album was called Writer, the first one under Carole’s name as a solo artist. Another great record, absolutely fantastic, and it went nowhere. So here comes the third record, Tapestry. I heard the songs and thought they were brilliant again, but now I was cynical. The first two records didn’t do anything, so my expectations weren’t too high.

“Lou Adler knew what he was doing, and he really felt that this would be accepted across the board. He described it like the movie Love Story; he said was it would be the ‘Love Story of albums.’ He had that vision, and he saw how those songs would fit into the cultural zeitgeist.

“My guitar playing on It’s Too Late was done live off the floor; it was all one take. I didn’t have anything worked out. For the solo, they wanted the guitar to have a sad, longing, nostalgic quality to it, but I already knew that because of the way the song is. I tried to play as ‘moodily’ as I could and get a vibe going.

“And believe me, I’m thrilled at how I went about it. Had I known how many times the song would get played, I would’ve gotten very self-conscious and I’d still be working on it. [Laughs] The funny thing is, that’s one of three songs we cut that day. We just hit it, and that gave it the easy, front-porch quality that it has.”

James Taylor - Mud Slide Slim And The Blue Horizon (1971)

“By this album, we’d been on the road together, and we had more experience with each other. There was more band interaction on this record. I kind of learned how to play the electric guitar on top of James’ acoustic. Russ and Lee had fallen into a groove, too. It was a lot easier for us to find the right parts to play.

“My song machine Gun Kelly is on the record. I was in a band called Jo Mama at the time. You know, James had the same difficulty as anybody: You made an album, you toured, and then you were supposed to make another album, with very little time to create material. When I walked in, I showed him Machine Gun Kelly, and he went, ‘Oh yeah, I can play that tune.’ We worked it out together, and it wound up on the album.

“You’ve Got A Friend was also on Tapestry. I think I played congas on Carole’s version – I didn’t play guitar on that one. When James cut it, it was the two of us facing each other with acoustic guitars, and away we went.”

The Section - The Section (1972)

“This record came about from us jamming on tour with James. He’d do his soundcheck, and then he’d leave and we’d keep playing. After a while, I said, ‘Why don’t we make an album of instrumental tunes and see if anyone is interested?’

“Of course, I was already enthralled by Booker T, The Meters, The Nightlighters, bands like that. But then, right around this time, the Mahavishnu Orchestra hit, and they seduced all of us. I used to go see them with David Crosby at the Whiskey A Go-Go, and I thought, ‘Holy mother of God – what the fuck? Listen to this!’ It was a game-changer. John McLaughlin floored me. I don’t think there’s anyone who can touch him, as both a guitarist and a composer.

“A lot of people were like, ‘Oh, man, I’m never gonna play again.’ I went home and started practicing. I picked up my guitar and started playing as fast as I could, finding scales and modes – I was completely thrilled. Mahavishnu really kicked me in the butt.

“The music affected Russ and Lee, too. They were knocked out. So we had a great time making this album. We made three records, eventually moving into more of a fusion thing. It was a lot of fun.”

Attitudes - Attitudes (1976)

“Jim Keltner was a legend in LA – when I met him, he was already legendary. I always thought of him as a jazz musician, and he was, but he’s also a great rock drummer. He’s in a class by himself. He was probably the most beloved musician in Los Angeles. He was really good friends with everyone, and I mean everyone. Through him, I met all The Beatles, all the Stones, all the great English musicians; I met Leon Russell and Harry Nilsson through him. He knew them all.

“Lucky for me, Jim took me under his wing. He was my rabbi. He’d take me to sessions and say to people, ‘This is Kootch, my guitar player.’ That’s all he had to say. He’d say that to Keith Richards, and then I was friends with Keith Richards. He’d say it to John Lennon, and suddenly I’m playing with John and Harry Nilsson. I am among several musicians in LA who owe a tremendous debt to Jimmy Keltner.

“We used to go down to the Record Plant, where on Sunday nights was something called the Jim Keltner Fan Club. Everybody you could ever fucking imagine was there. After a while, it began to refine itself down to a few people – Keltner, me, David Foster, and a fantastic bass player and singer named Paul Stallworth. Suddenly, we’re making an album. Because Jimmy was such good friends with George Harrison, George signed us to Dark Horse Records.

“We made two albums that way. This was some of the first stuff that David Foster did in LA. There was no question in my mind that David was going to be huge, huge, huge. He had badass feel on keyboards; everything he played on sounded better right away. He had a great attitude, and he wasn’t on dope like the rest of us. [Laughs]

“He was just a winner. I remember telling him once when I was driving him to the Roxy Theater to play in the house band – he didn’t have a car yet – and I said, ‘Foster, a year from now you’re going to hire somebody to answer your phone. You’re going to be doing so well, I promise you.’ Sure enough, that’s exactly what happened. I wasn’t surprised at all.”

Jackson Browne - Running On Empty (1977)

“I had known Jackson for many years. I met him when he was only 18 or so. We used to run around and jam around together. I always thought he was absolutely brilliant, as everyone did.

“Running On Empty came about because Jackson wanted The Section to open his show. We played for about 40 minutes before he came on. When we first started rehearsing, he was actually a little unsure about me. I had to find my place, but there were no role models. He already had David Lindley, who would play these beautiful lines behind Jackson. I had to figure out a way to play so I could contribute.

“I tried a bunch of different things, but Jackson was getting nervous. Finally, I had to take him aside and say, ‘Listen, I’m working on a bunch of things, and I’m going to refine what I do. I’ll have stuff that will work and will help your songs.’ Sometimes it takes a little time.

“Jackson was a big R&B and soul fan, which is where I was coming from. A song like Love Needs A Heart, to me, that’s an R&B song, straight up and down. I started to use what I thought would work, coming from what I thought Steve Cropper or Cornell Dupree would do, or maybe Marvin Tarplin from The Miracles – those were my role models. Nobody else in the band was doing that, so I was able to find my niche.”

Warren Zevon - Excitable Boy (1978)

“With this record, it did feel like something was different, that this was Warren’s time to break through. He was highly respected as a writer and singer, and everybody loved him – he was good friends with Waddy and Jackson. When I met him, I thought he was a terrific guy – very smart and a lot of fun to be around.

“He didn’t know exactly what he wanted. In terms of going around and telling people what to play, he didn’t do that. A lot of times when you do sessions, they call you to do what you already do; they don’t call you to give you directions or to make you play like somebody else. There are plenty of guys out there that can play whatever you want. ‘You want country?’ Bang. ‘You want heavy metal?’ Bang. But with me, I had one way of playing – my way – so when I’d get called, they just let me go. I was always called to be myself.

“Warren was pretty nervous making this record. He’d made a record before this that had Hasten Down The Wind on it. This one, though, was going to be the breakthrough. Jackson and Waddy were producing, and a lot of legendary people were involved in it. Warren was also drinking heavily during this period, but he eventually gave that up. He was nervous about the spotlight beaming on him.

“Warren was a very intelligent, intellectual guy, so it was always intriguing to be around him. He knew about movies and literature and history – a very bright fucking guy. Harry Nilsson was like that, too – very, very smart. Both of those guys, their first hits were by done by other people.

“Everybody thought Werewolves Of London was going to be a big hit. I loved it – I thought it was catchy and groovy – but was it a hit? I wasn’t so sure. I didn’t trust my judgment because I had been wrong so many times before. Lou Adler was great at that, but Waddy and I… we dug what we dug. Thankfully, it was big. But you know, they tried many times to get the feel right on that. They used three or four or five different rhythm sections. Finally, they called in the Fleetwood Mac guys [Mick Fleetwood and John McVie], and that’s when they got the feel right.”

J.D. Souther - You're Only Lonely (1979)

“When J.D. played me the song You’re Only Lonely, I thought it was great, but you know, I’d heard other great songs that didn’t go anywhere. I’ve never been the kind of guy who went, ‘That’s a hit!’ There were so many songs that I thought were hits and weren’t, and a lot of songs I hated that became hits. You never know.

“J.D. and I had hung out a lot together. We had the same taste in music – he loved soul and R&B, too. He taught me a lot about classic country music, which I wasn’t too familiar with. It was a terrific learning experience hanging out with him. I think we both rubbed off on each other.

“Everybody knew each other. We all ran around together, all the musicians and the singer-songwriters. Jackson, James, Henley and Frey and me – we used to drink together and play music for each other. It was a nice community. Making this record was a great experience, and I was thrilled when it became a hit for J.D.”

Linda Ronstadt - Mad Love (1980)

“It was a strange period, a real transitional phase in music. I had become a huge Elvis Costello fan. His first album, My Aim Is True, I bought it because I liked the cover. I got the cassette and listened to it in my car over and over, hundreds of times. I told everybody how fantastic it was. I went to see Peter Asher, and I told him, ‘This guy is the bomb. I love what he’s doing!’ I even liked the way he dressed. It felt so fresh to me.

“At that time, we were coming from the singer-songwriter thing. People were walking around in promo T-shirts and jeans and sneakers, and wearing shaggy haircuts and stuff. I hated it. To see how punk bands were dressing, I thought it was fun. It was cool. I said, ‘This stuff is fun. I wanna have fun, too.’ I wanted to wear jackets with skinny lapels and skinny ties. I was tired of looking like a hippie. Fuck that shit – I hate fuckin’ bell bottoms! [Laughs]

“Waddy was stuck in his ways, and by the way, that’s to his credit. He has a very definite way of playing, and he knows who he is. He can also make himself fit into situations you wouldn’t believe. I don’t know if he quit or walked away, but I found myself there to play with Linda in a bit of a new context.

“The way I saw this record was like what Billy Joel says: ‘It’s still rock ‘n’ roll to me.’ It was fun, and it had energy. I remember telling Peter that Elvis Costello was playing at Hollywood High School, and he got tickets for the bunch of us – me, Linda, Andrew Gold, we all went. Linda heard those tunes, and she went, ‘Hey, those are great songs.’ She couldn’t care less what anybody else thought. She followed her own drummer, to quote from one of the songs. There’s nobody smarter than her.

“The songs we played were fun and groovy. A lot of people from the ‘70s might have been intimidated, but I wasn’t one of them. I thought what we were playing was great. It was a kick in the ass, and I was thrilled that we were creating something that felt upbeat. The bottom line is that Linda was singing songs that she loved at the time. She wasn’t trying to go punk or new wave. She was following her instincts.”

Don Henley - I Can't Stand Still (1982)

“The Eagles broke up. Glenn went off to make a solo album, which I played on – Lee did, as well. Don felt like he had to do something too, and he had to do it right away. He started putting out feelers, and I remember hearing that he was calling people. A lot of guys went up to his house to jam with him. It was obvious that he was looking for somebody to collaborate with.

“I knew he would call me. I knew that the phone would ring and it would be Don. Sure enough, the phone rang and it was Don: ‘Come on up. Let’s jam.’ He told me what he was doing; he was making a solo album, and he was looking for collaborators. I had a sense that I was going to get the gig, because I was writing, and I had a ton of ideas. I was ready. I went to see him, and after a few hours, he looked at me and said, ‘OK, you wanna work on this album with me?’ [Laughs]

“After that, we saw each other every day, and we became very, very good friends. I love him him very much. We threw ideas around, listened to records. He had a lot of ideas, and we had to find ways to make those ideas into songs.

“He never said what he was looking for in a collaborator, but he knew what he wanted to do. I think one of the reasons he picked me was because I had broken into new things. I was interested in new wave, I was interested in punk, I was interested in synths – and I was one of the only cats from the scene who was into that stuff.

“Don didn’t want anything that sounded like the Eagles. He didn’t want acoustic guitars, didn’t want harmonies, didn’t want ‘oohs’ and ‘ahhs’ – nothing that was associated with the Eagles. We kept saying, ‘Yeah, the record ‘s gonna kick ass! It’s gonna have big beats and hard guitars.’ We used to pump each other up like that.

“The synth part to Dirty Laundry? He didn’t say, ‘That’s not me.’ He knew we had to make a ‘me’ – we had to make what Don was now. ‘What does Don do now that he’s not in the Eagles? What does Don do in 1981?’ That was the general idea. He knew that I was the guy to help him do it. He talked about Dirty Laundry from day one. He wanted to take on the local media, which had really raked him over the coals.

“One night, I was at home in my little demo studio, working on tracks, which is how Don liked to work – you’d come in and play him something, and he’d say, ‘Oh, I can write a song to that.’ I played him a primitive demo of what became Dirty Laundry, and he loved it. It sounded new and different. It all went from there.”

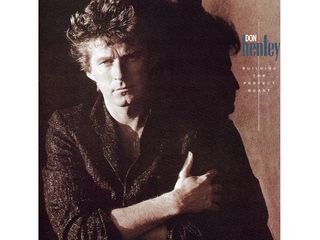

Don Henley - Building The Perfect Beast (1984)

“It was the same kind of process. We went song by song. There’s stuff on here that doesn’t sound 'new wavey' or modern. There’s one called A Month Of Sundays, which is a very nostalgic, Texas-style tune, and there’s Talking To The Moon, which Don wrote with J.D. I had to convince him to do that one. He wanted to save it for a movie. I was like, ‘Man, you gotta record that one for the album. It’s a great song.’ I was surprised that it wasn’t a single.

“It kind of ran the gamut. There’s the title track, which is a little like Devo or something. We were using a lot of machinery and what was available to us. We had one of the first Linn Drum machines.

“All She Wants To Do Is Dance, the way that came about was, we’d been hearing about this new instrument called the DX7, which is now like a Model T Ford, but at the time it was the newest, greatest thing. Henley had to have one. He sent his guy, Tony Tavia, out to get one – he found one in Dallas. It arrived, I set it up, and I thought it was so cool. There were sounds on it I’d never heard before.

“I took it home and started messing around, and that’s what you hear on All She Wants To Do Is Dance. It’s this sample-and-hold thing. I slowed it way down and put it through a Marshall amp. I made a demo of it in about 20 minutes, played it for Don, and he said, ‘Great. Let’s cut it.’

“You can imagine having Don Henley as your muse, being able to write a song and he’s cutting it the next day – I was beside myself. I must say that it spoiled me forever. There were no budgets in those days; we did whatever we wanted. Don had a lot of faith in me and what I was bringing to the table.

“We started using the cats who were our pals. We brought in the guys from Toto, David Paich and Steve Lukather – stone geniuses – and Jeff Porcaro, one of the best ever. From the Heartbreakers, there was Ben Tench and Mike Campbell, two guys who had their own approach, and they played gorgeous, gorgeous stuff. The best guys were just a phone call away. I absolutely loved making this record. What a great experience.”

Jon Bon Jovi - Blaze Of Glory (1990)

“I had been producing Don, and I got a call from Jon Bon Jovi – the last thing I expected. He liked the stuff I’d done with Don, and I guess he’d asked Jimmy Iovine about me. Jon told me that he wanted to do a solo album, but it was kind of a clandestine thing, music from Young Guns II, a totally crappy movie. But this is what he wanted to do and how he wanted to get his feet wet as a solo artist. Talking to him on the phone, I thought, ‘I like this guy.’

“He sent me a demo of the songs, and they were really good. Also, I thought that I could learn from him. He knew stuff I didn’t ‘cause he was coming from a completely different place from me musically. I wasn’t a fan of heavy metal, hard rock or hair bands, and I can’t say that I was a fan of Bon Jovi, either. I liked Livin’ On A Prayer, as we all did, but the rest of it I could’ve lived without. But I thought that this could be fun and different.

“Jon had Jeff Beck – Jeff had agreed to play on the album – and that was a big deal for him because he was a huge fan. Jeff had suggested his own band, but I didn’t think they’d be right for the record; I thought we’d be better off with guys who played pop-rock. My first call went to Kenny Aronoff, whom I didn’t even know, but I just had a feeling he’d be right. Then I called Randy Jackson – I’d done a lot of sessions with him, and I knew he was great. I also knew that once Jon took a look at Randy, he’d go, ‘This is my guy.’ Randy was big, he had a square haircut, and he had a vibe like no one else. He could walk into a room and just light it up, as well as being such a badass bass player.

“I called Ben Tench, who was dubious. Ben isn’t the kind of guy who goes, ‘Sure, what time?’ He wants to know what the music is, who else is involved – he’s not a session guy you just call for dates. Money isn’t enough for him; it’s gotta be for real, from the heart. But I convinced him that the songs were really good, and I told him, ‘Look, it’s Waddy, it’s Randy Jackson and Kenny. This will be fun, I guarantee it.’ So I convinced him, and he loved it. He had an absolute ball. We all did, including Jon.

“I spent a week in the studio with Jeff Beck doing overdubs on his solos. It was beyond hilarious. He’s Jeff Beck! He’s beyond legendary. I learned a lot by watching how he manipulated his guitar. He’s always changing things – his pickups, his tones, his volume. He’s always using the whammy bar; it’s just a whole different way of playing. And his thumb – he’s got this huge thumbnail. You could open up soup cans with it.

“I think that Jon wanted to expand what he was about. I think he wanted to work with guys who were taken more seriously perhaps than Bon Jovi were at the time. They were certainly taken seriously by their fans – in the music world, they were huge. He wanted to find out what it would be like to play with guys he wasn’t in a band with; he wanted to work with the elite troops, which is what we were. The guys who played on this record were the best musicians in Los Angeles.”

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.

“How do people do that? No click, he played through it and ‘bam’”: Prince’s ability to keep time when he was recording drums was remarkable, says his engineer, but it also made things difficult during the editing process

“I’m not the technical producer, I’ve learned how to use a compressor but I haven’t learned why it does what it does”: Revisiting the intuitive production skills that made Avicii a superstar

“How do people do that? No click, he played through it and ‘bam’”: Prince’s ability to keep time when he was recording drums was remarkable, says his engineer, but it also made things difficult during the editing process

“I’m not the technical producer, I’ve learned how to use a compressor but I haven’t learned why it does what it does”: Revisiting the intuitive production skills that made Avicii a superstar

Most Popular