Production legend Bob Ezrin talks about 11 career-defining records

In his remarkable 40-plus-year career, one which has resulted in touchstone hits for upstarts and superstars, shock rockers and progressive pioneers, producer Bob Ezrin has invariably taught more than a few artists a lesson or two. Asked to recall the biggest kernel of wisdom he's ever gleaned from his years in the studio, the record maker sums it up by insisting that the art of music is all that matters.

"When your motivation is to simply be successful and sell records, you’re going to fail," Ezrin says. "But if you’re interested in doing something excellent and producing work that matters, you’re going to succeed. The best artists I’ve worked with have always obsessed over their work; they’ve paid very little attention to the market that it goes into. They know that the art is all that counts."

Barely out of his teens, Ezrin absorbed the ins and outs of record making from Jack Richardson, the late Canadian music giant who helmed a string of hits for The Guess Who and started the Toronto-based Nimbus 9 Productions. While Richardson's protege, he received a full year of training that involved everything from how to wrap a mic cable to writing string charts. "Jack taught me everything there was to know about recording," Ezrin says. "He kicked my butt before he turned me loose on the world with Alice Cooper. But at that point, I was a pretty knowledgeable, confident guy. I'd gone through my apprenticeship."

Along with Richardson's son Garth, himself a noted record producer whose credits include Rage Against The Machine and Biffy Clyro, among others, Ezrin started the Nimbus School Of Recording Arts in Vancouver in 2009. The motivation for establishing a teaching institution was not altogether altruistic, as Ezrin explains: "Garth and I were talking about the number of people we had to fire, which was pretty incredible. We kept finding that so many young people were lacking in some areas and had an overdeveloped sense of entitlement. We need good people to work with, and we figured, if can’t find them, we should develop them ourselves."

Already, Nimbus is turning out success stories (a number of graduates now work at Richardson's Vancouver facility, The Farm), but its young alumni will have a ways to go to match the achievements of its co-founder. On the following pages, Ezrin takes a look back at his times behind the studio glass and shares stories behind the making of some of rock's greatest masterpieces.

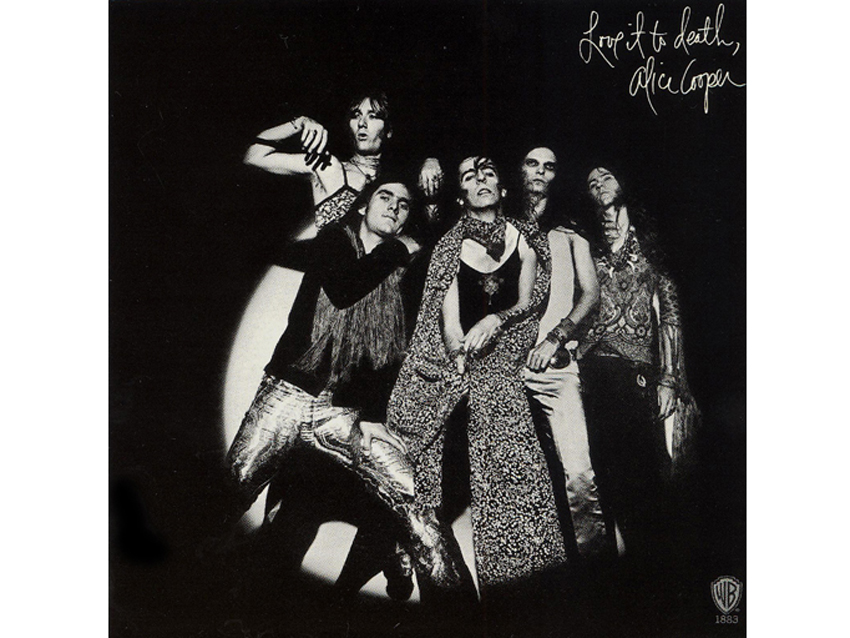

Alice Cooper - Love It To Death (1971)

“They wanted my boss, Jack Richardson, to produce the band. He had produced The Guess Who, which was about as far-out and raunchy as he wanted to get. When [Cooper manager] Shep Gordon walked into the office with copies of Easy Action and Pretties For You, Jack took a look at the pictures of the band and wanted nothing to do with them. He said, ‘I’ll send the kid – meaning me – to see band.’ My instructions, however, were to get rid of them.

“I went to see the band at Max’s Kansas City in New York, and I fell in love with them. Rather than get rid of them, I said that we should do it. Then I had to go back and plead for my job, because I did exactly the opposite of what I had been sent to do. I argued so annoyingly that Jack finally said, ‘Enough! All right, if you like it so much, you do it.’ That’s how I got the job.

“When I first heard I’m Eighteen, I actually thought Alice was singing, ‘I’m edgy.’ I told the band that I really loved that song ‘Edgy,’ and they thought I was crazy. I didn’t know why they looked at me so unsure. But when they told me the line was ‘I’m eighteen, and I don’t know what I want,’ I said, ‘Wow, well, that’s even better!’”

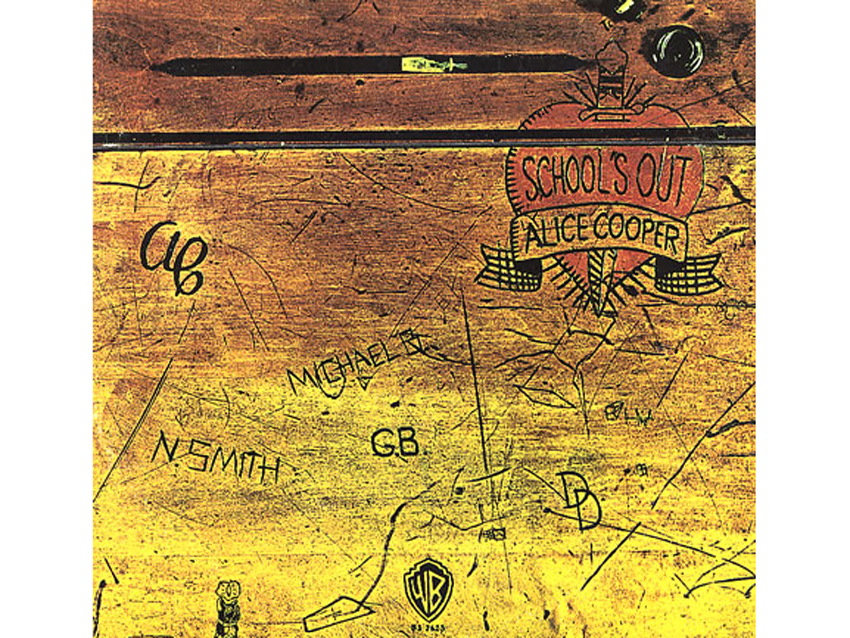

Alice Cooper - School's Out (1972)

“Once we started working together, we became a team. It wasn’t broke, so nobody wanted to fix it; whenever it was time to make a record, they called me.

"The song School’s Out came from [guitarist] Glen Buxton, who came up with this amazing riff. Shep called me in Toronto and said, ‘I think the boys just wrote a hit. You need to get out here.’ I met them in LA and we went into a rehearsal room. They had the beginnings of the song; we put it all together, and it became a big hit record.

“It was a fun album to do, and it the first one we did outside of Chicago. We had been making records at the RCA's Mid-America Recording Center, which we really loved, but when the band started to take off, it was thought that we should embrace New York and take that city by storm. The best way to do that was to move everybody there.

“I had worked at A&R Studios in New York with Phil Ramone, but I also knew that [engineer] Shelly Yakus had moved over to this hot new studio called The Record Plant. So we went there to give it a try, and from the moment we walked in, we knew we were in the right place.

“The guys in the band were kind of like The Jets from West Side Story; they were snot-nosed Bowery Boys. That’s how they acted, and those were their references. We decided to do some portion of West Side Story and turn it into a thing. It was also a bit of an indulgence for me. But it worked out well – I listen to it now, and while it sounds kind of primitive, it has a lot of charm. The audience really appreciated it.”

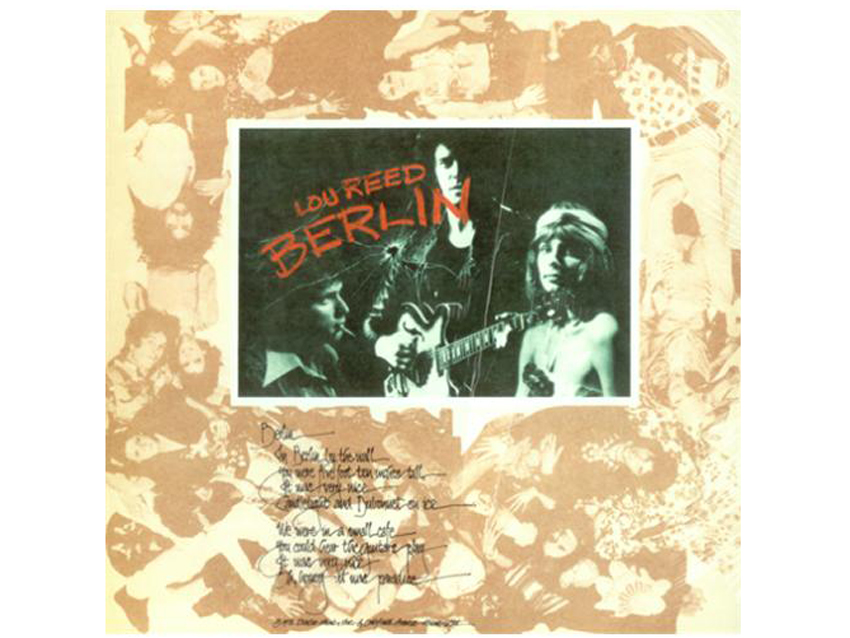

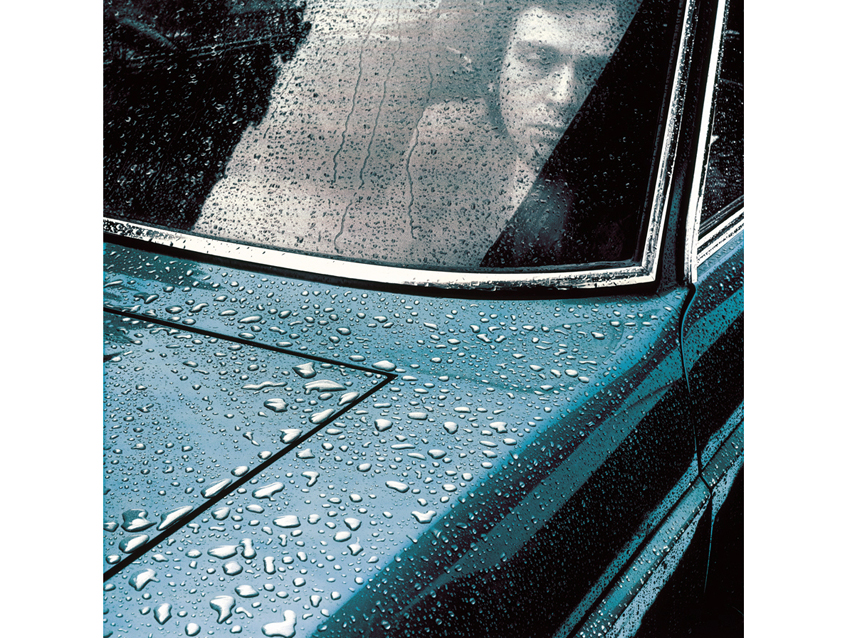

Lou Reed - Berlin (1973)

“I had done an album with Mitch Ryder and his band in Detroit, on which we covered Lou’s song Rock & Roll. Lou heard it and said, ‘I want to work with the guy who did that.’ I went to go see Lou play a show in Toronto, and afterwards we started talking about the project. Eventually, we wound up sitting on my living room floor, playing songs and kicking around ideas.

“I said to him, ‘You wrote all of these amazing snapshots of people’s lives, these four minute portraits, but what happens with them? The stories only go so far.’ I used the two lovers in the song Berlin as an example, but I said, ‘Wouldn’t it be cool to tell the whole story? Why not do something like that?’ He thought that was a great. Then we decided to not do something ‘like’ that; we were going to do exactly that.

“He went home and started writing, and when he came back with the guitar-and-vocal versions of some of these songs, it was chilling. He had done such a phenomenal job. It was then my job to take the tunes and turn them into something more orchestrated in the rock sense. It’s a fantastic record. They just remastered it last week, and Lou called me from the mastering room to tell me how beautiful it sounded.”

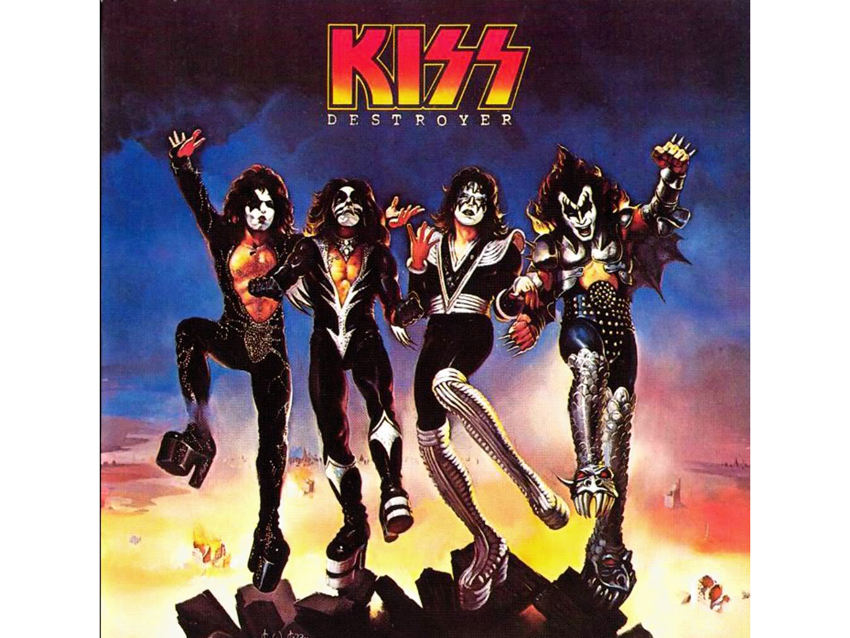

KISS - Destroyer (1976)

“I didn’t know who KISS were, but there was this little kid in Toronto who used to phone me – this was back when my number was listed – and he would tell me what was hot, what was not, what I should be listening to, what I should be producing. He was like my own personal fanboy. He called to tell me about KISS. ‘They’re amazing, but their records suck. You should produce them.’

“Their records didn’t suck, but I understood what he was saying – they could have been more sophisticated. It was pretty prescient of him to say, and he was dead right – we should be working together.

“When the song Beth was first played for me, it was bouncier, with almost a country or rockabilly vibe to it. It was also a little chauvinistic, like they were saying, ‘Me and the boys, we got something going on. You can sit there and wait.’ It was also called ‘Beck.’

“I asked them if it was OK for me to take it home to mess around a little bit, and Peter [Criss] said it was fine with him. I came up with the piano thing, which started to define it as more romantic and sensitive, so I changed the lyrics. First, I called it ‘Beth,’ and then I added stuff about ‘our house is not our home,’ along with a sense of sadness and loss about the death of the relationship. But that line ‘I hope you’ll be all right’ – that was important.

“I played it for everybody, and they thought it sounded good and that we should try it. I don’t think they realized how important it would be for them until they heard it being recorded during the orchestra date. I played piano on it – they’d heard my piano part before. But the orchestra really made them think, ‘Wow, this is going to be important.’

“And it was. When I had first gone to see the band in Saginaw, Michigan, they were playing to 15- and 16-year-old boys. It was amazing – hardly a girl in the place. I thought, ‘Here’s a great opportunity.’ Their whole show was so dick-swinging macho that I couldn’t see girls getting into it. I told them that I wanted them to be the bad boys, but they should be the bad boys that every girl wants to save. There had to be a little bit of vulnerability.

“The whole idea of the album was to show some sensitivity; it wasn’t going to all be cock and balls. One of the first songs to come up was Do You Love Me? For me, that was the best symbol of what I was hoping to do with the record. As it turned out, that one never became a hit single, but it did inform the project.”

Peter Gabriel - Peter Gabriel (1977)

“This was at a very important time in Peter’s life. There was so much going on, so many questions. He wasn’t entirely sure what he wanted to accomplish, but when we got together, we decided to explore. We sort of had a better idea of what we wanted to do with a stage show than the music.

“I moved Peter and his wife, Jill, and their daughter Anna to New York. I rented them Garson Kanin and Ruth Gordon’s apartment – a really magical place. You've got one of the greatest writers with Garson, and then there's Ruth, who was in Rosemary's Baby. Anyway, Peter would come to my apartment on 52ndStreet. He would sit at the piano and noodle around while I was in my office upstairs, and every time I heard something I liked, I would run out and say, ‘Let’s record that!’ We would put everything on cassette. Eventually, we assembled a bunch of pieces we really liked, a sense of a direction musically, and that’s when Peter went back to England to flesh it out.

“The next time we got together was in Toronto, when it was time to do pre-production for the record. We did it at the same studio where I’d recorded Love It To Death, and actually we used many of the same musicians.

“It was a brilliant experience for me to work with Peter, and it has been every time we’ve worked together. We’ve managed to do it a number of times over the years, and we’re still great friends. I truly love that man and his family. I find him to be so stimulating to work with. He’s a real artist with a capital “A.’ And he elevates my game, absolutely.”

Pink Floyd - The Wall (1979)

“The Wall is a crowning achievement technically, lyrically and musically; it’s one of the things that I’ve most proud of having been involved with. Everybody was firing on all cylinders and was at the peak of their conditioning and talents. The end product shows that generations are still discovering the album, which for me is one of the most gratifying things about it. I really consider it to be a work of art.

“Roger’s fiancée, Caroline, had worked with me in London. We had hired her to be our rep for some of the things I was doing – Lou Reed, Alice Cooper – so when Roger started to noodle with the idea of bringing a producer into the project to work with the band, she said that he ought to talk to me about it. A side note: When I first started working with Alice Cooper in 1970, they were into British art rock and listening to things I’d never heard of – T. Red and Pink Floyd. They played me my first Pink Floyd, and I fell totally in love and became a monster fan.

“Actually, this story goes before then: When Pink Floyd were in Canada on the Animals tour, Caroline had called me to say hi, and I invited them over to the house for a barbecue. Roger couldn’t come because he was soundchecking, but Caroline invited me to the gig, and she said that we would all ride out to the show together. I was in the limo with them, and Roger said something about wanting to build a wall between the band and the audience. I think I said, ‘Wow, that’s a great idea, Roger.’

“So later, after Caroline had mentioned me to Roger and he felt comfortable with the idea, he sent [manager] Steve O’Rourke to New York to talk to me about it. Steve asked me if I would go out to the country to Roger’s house to listen to demos. I did so, and we listened to two projects, one of which became The Pros And Cons Of Hitchhiking and the other was The Wall. At this point, Roger wasn’t sure which one he should do. I believe everyone was unanimous in picking The Wall as the one to work on. I certainly was. While they were both great, that's the one that touched me the most.

“Working with Roger musically and conceptually was always incredibly stimulating. Sometimes it was difficult, but it was also exciting and thrilling and very challenging. There were so many things going on. There was never a moment where Roger and I looked at just a verse of a song; it was always part of something bigger.

“With Roger, it was like working on a theatrical production; with the other guys, it was like working with a rock band. They were all great. Nick [Mason] was a delight to be with, really smart and funny. Rick Wright was a gentle, sweet man, but at the time he was feeling very self-conscious about his relationship with Roger. I felt sorry for him on certain levels during that time, and I sometimes had to stand up for him. He wasn’t a fighter; he was always more of a passive guy.

“And David… working with him is always a stone musical thrill. He’s one of the greatest players of all time. He does it in a very understated and un-self-conscious way. Sometimes you would think he has no idea how great what he just played is. He just knocks it off and has some tea, and you’re standing there going, ‘Oh, my God... I just heard the best thing in my entire life.’

“Like the solo on Comfortably Numb. That was one take – and not only one take, the first take! The first time he ever played it, that’s what came out. We tried 100 times to make it better, but we never could. The first time I heard it, I said, ‘That’s the best solo I’ve ever heard.’ David said, ‘No, no, I can do better.’ He kept trying until he finally gave up, and he realized that we had the best one.”

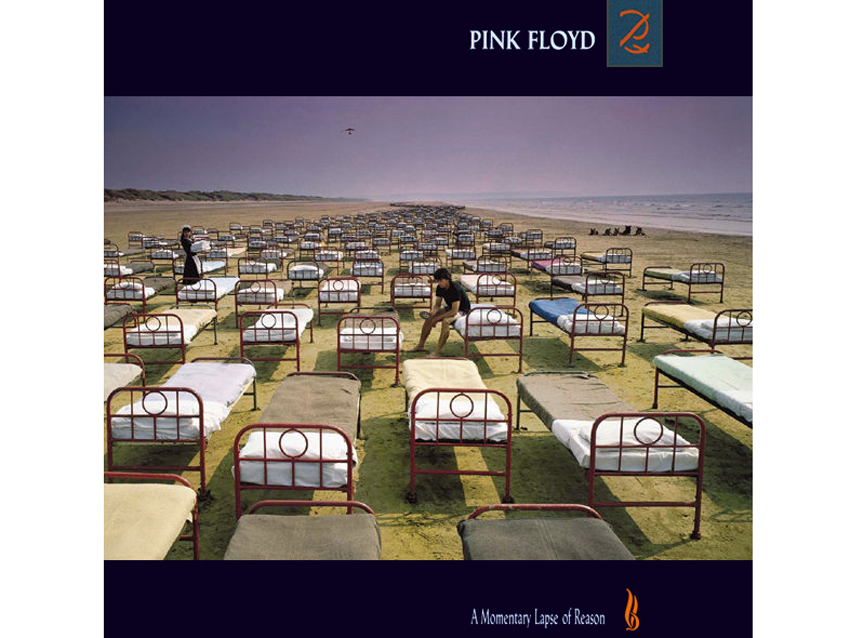

Pink Floyd - A Momentary Lapse Of Reason (1987)

“I had done The Wall, and then there was a conflict between Roger and me. It was two-pronged – one side was really my fault, and the other part was out of my control.

“I had signed an NDA [non-disclosure agreement] about The Wall and everything we were doing with it. One day a friend a mine, who also happens to be a rock journalist, called me to tell me that his magazine wouldn’t pay for him to see The Wall – we were about to do the live show in LA. He said, ‘You know how much I love the band, so just between us, what am I missing? What am I not going to see?’ I asked him if this was off the record, and he said, ‘Off the record, absolutely.’

“I was just about to sit down to dinner, but I was really excited about the show, so I told him some of the things we were doing. The next week in Billboard it said, ‘Over dinner with Bob Ezrin,’ and it revealed some of the details. This put Roger into an apoplectic fit – rightly so. He had worked so hard to keep it all a secret, and then the secret was out, and it appeared to be my fault. It was my fault. I was naïve in believing that there was such as thing as ‘off the record.’

"I was banned after that. They used Michael Kamen for the next record, The Final Cut – I had brought Michael in to work on The Wall. Roger wouldn’t talk to me. Finally, some years down the line, I got a call from him asking me to come to England to talk about a new project. ‘Pink Floyd is no more,’ he said, ‘and they wouldn’t dare go on without me.’ I told him that I couldn’t go to England right then – I was either doing Rod Stewart or Berlin – but we agreed to meet in New York.

"We got together, and the first thing he did was apologize. He said, ‘I was very hard on you, and I’m sorry. It was a difficult time in my life, and I was perhaps a little unfair.’ I was so happy to have Roger Waters back in my life, because I love him. He’s one of the most brilliant people I’ve ever known.

“We had a great time, we bonded, and he told me he wanted me to produce the new album. I said that I was very interested, and that was that. We started to try to make arrangements, but it was very, very difficult. I had to go to England to work with him, and once we started, we couldn’t stop. Basically, I had to move my family, which involved many things – it all became more and more difficult. One night, my wife broke into tears. There was so much involved with our family going to England. We were going to have to leave the dog boarded for months; the kids were going to have to enroll in these other schools. Finally, she said it was too much and that I can't do it.

"I called Peter Rudge, who was the manager at the time, and I said, ‘Peter, I can’t do it.’ He was like, ‘Oh, you’re killing me. I don’t want to have to give this news to Roger.’ I told him I was so sorry, that I had honestly tried. And we were already pretty far down the line heading towards the record. It was pretty late to be pulling out. But at the end of the day, my wife wins. That was that.

“Literally, three weeks later, I got a call from Dave Gilmour telling me, ‘Roger’s left, but we’re keeping the band together. We’re doing an album, and we’d like to know if you’d work with us. We have some song ideas – may I come to LA to show them to you?’ I said, ‘Yeah, sure.’ 'Cause, you know, I love Dave, too. Dave and the band are amazing talents, so I was really excited.

What was different was the fact that Dave said, ‘Look, you’ve got a family, I’ve got a family – why don’t we split it up? We’ll do a bit in England and a bit here.’ It was so much easier and more accommodating of my family situation, so I said, ‘I’m in.’

"Roger got very angry, and he believed that I knew I was going to do this before I’d pulled out of his project. In a way, he sort of believed a conspiracy, that I'd strung him along so that he’d be late and wouldn’t be able to his record out before Pink Floyd. None of which is true – I had no thoughts about any of that. I just felt more comfortable with the situation and that we were going to do a lot of it in LA, where I lived.

“Anyway, we started Momentary Lapse. We began in this Victorian houseboat boat that David had bought – a brilliant piece of architecture. It was a very fertile environment; the water was gorgeous, and the ideas were flying. We had a great time.”

Catherine Wheel - Adam And Eve (1997)

“This was my coming-out-of-retirement record. I had hit a wall with record production and decided to concentrate on my new media company, 7th Level. We made games and educational software for computers and were the first to bring animation to the desktop. I was thrilled and excited by it – records weren’t turning my crank.

“Merck Mercuriadis, who was a senior agent at Sanctuary – actually, he went on to be the head of Sanctuary – he’s a Toronto boy who’s familiar with my career. When he moved over to Sanctuary, one of his clients became Storm Thorgerson, my dear and recently departed friend. I guess they were talking about how I should be in the studio. It started off with Merck coming to me at 7th Level and talking about getting Storm in the world of interactivity – a Storm CD-ROM – but in every conversation we ever had, he would say, ‘But you know I’m gonna get you back in the studio.’

“And he did. He just kept pushing until he hit the right button, which was Catherine Wheel. I met [singer-guitarist] Rob [Dickerson] and went to a band rehearsal. Seeing them play in a room and listening to Rob’s voice made me fall in love with the idea of working with Catherine Wheel. I just think that Rob is such a huge talent.

“This was a foray back into the studio side of my life at a time when I had other responsibilities. I agreed to do the album with a group of folks; I didn’t want to be the guy on the line every day. I spent as much time as I could with them and did as much work as possible. I really enjoyed all of it, particularly the mixing process – I loved that.”

30 Seconds To Mars - 30 Seconds To Mars (2002)

“Arthur Spivak, the band’s manager, is a friend of mine, and he called me when Jared Leto first decided to do this. I also heard from another friend, Tony Berg, who was the A&R guy for the band. They all thought, because of the dramatic nature of the project, that it would be a natural for me.

“And they were right. I think Jared is just brilliant. This is a guy who has a singularity of vision and an obsessive nature. He knows what he wants, and he will keep slugging till he gets to the point that he’s aiming at.

“The first album was a bit of a learning experience for Jared and a great developmental step, and it’s pretty good. It’s not as good as the 30 Seconds To Mars albums that came over time – he definitely honed his craft and learned pretty quickly. He’s a major talent.

“We’re all naturally curious about actors who try to step into doing something else – how much do they mean it? But the Leto brothers have been playing together for a long time, and it was always a dream of theirs to be rock stars. Same with Johnny Depp, who moved to LA to get a deal for his band. It’s hard for some of these guys who have talents in different areas – people can be skeptical. Jared is a compelling actor, magnetic actor – his presence on the screen is undeniable – but history has proved him right as to his first career choice.”

Deftones - Saturday Night Wrist (2006)

“I was with the band at a transitional time for them, so it was kind of a tough record. At the end of the day, I don’t know if we were a great fit. Contrasting this experience with working with Deep Purple, there was some conflict, and there were times when we almost came to blows – or at least Chino and I did.

“They’re all incredibly talented, and they’re very unique in terms of where they grew up, their cultural geography and their individual tastes. You put it all together and you get a really eclectic and artful band.

“I wish that Chi were still here. I felt a deep affection for him and really enjoyed working with him. He was very creative and sensitive."

Deep Purple - Now What?! (2013)

“It came together when Neil Warnock, the founder of The Agency Group, came to me and said, ‘I want you to produce the next Deep Purple album.’ And, actually, I said, 'I don't think so,' because I was already working with Alice Cooper, and I didn’t want to be thought of as an oldies guy. But he said, ‘Yeah, but this is different. You need to come and see the band.’

“I went to see them, and halfway into the set they did this jam where they’re like a four-man orchestra. Steve Morse, Don Airey, Ian Paice and Roger Glover – each guy, in his own way, is like the best player to hit a rock stage. And when Ian Gillan sings those classic songs, he’s still got an incredible voice. They knocked me out. But what impressed me was how the audience reacted to the stuff they used to do, the kinds of things nobody is doing anymore. That’s what moved the audience the most.

“I went to talk to them, and I told them, ‘If you want to be a contemporary band and vie for radio play, you’d better talk to somebody else, ‘cause I don’t think it’s possible. You can’t compete with the bands of today on their turf. But if you want to be resolutely yourselves and make a quintessential Deep Purple album, then we have something to talk about.’ And Roger said it best: ‘We want to put the deep into Deep Purple again.’

“This album was made to capture what the band is without trying to make them something they’re not. We were fanatical about this being a true Deep Purple record. There weren’t moments of intense conflict, but occasionally I did say that something needed to be a different way than what it was. Thankfully, they responded to my ideas and were excited by them, and we developed a relationship of confidence and trust.

“It was a really natural collaboration. We all had a similar musical language – if not exactly the same, it was still one we understood. Everybody came to work every day excited about what they were doing, and they gave it their very best.”

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.

“If they were ever going to do the story of Nero, probably the most decadent of all the emperors, they would have to use Roy Thomas Baker”: Tributes to the legendary producer of Queen, Alice Cooper, Journey and more, who has died aged 78

“A fabulous trip through all eight songs by 24 wonderful artists and remixers... way beyond anything I could have hoped for”: Robert Smith announces new Cure remix album

“If they were ever going to do the story of Nero, probably the most decadent of all the emperors, they would have to use Roy Thomas Baker”: Tributes to the legendary producer of Queen, Alice Cooper, Journey and more, who has died aged 78

“A fabulous trip through all eight songs by 24 wonderful artists and remixers... way beyond anything I could have hoped for”: Robert Smith announces new Cure remix album

![Gretsch Limited Edition Paisley Penguin [left] and Honey Dipper Resonator: the Penguin dresses the famous singlecut in gold sparkle with a Paisley Pattern graphic, while the 99 per cent aluminium Honey Dipper makes a welcome return to the lineup.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/BgZycMYFMAgTErT4DdsgbG.jpg)