Peter Asher in 1965, during the height of his fame as part of Peter And Gordon.© Hulton-Deutsch Collection/CORBIS

By any measure, Peter Asher has led one heck of a pop life. By 19, as half of the duo Peter And Gordon, he'd already had a No. 1 hit on both side of the Atlantic with the song A World Without Love. (Of course, it didn't hurt that the infectious number was penned by Paul McCartney - the famous Beatle was dating Asher's actress sister, Jane.)

After a few years of singing stardom, Asher grew enamored with record production. He assumed greater control over Peter And Gordon recordings, produced a couple of albums that drew favourable notices, and so, when The Beatles set up Apple Records in early 1968, Asher was picked to head the A&R (Artist & Repertoire) department.

"Right time, right place," Asher says in a somewhat self-deprecating style, before adding, "But you do have to have an idea of what you're doing. Even though those days were a bit crazy and things were moving and changing so quickly, we did have a pretty clear vision for what we wanted to do with Apple, which was to create an environment where we could find and promote talent that otherwise might not get a fair shake elsewhere. We took it very seriously."

On 26 October, Apple Corps Ltd. and EMI Music will release 15 key albums - remastered, available digitally as well as physically, with many containing bonus cuts - from the Apple Records catalogue by artists such as Badfinger, Jackie Lomax, Billy Preston, Mary Hopkin, and a little-known singer-songwriter and guitarist named James Taylor, whom Asher personally signed and produced.

Taylor's debut album for Apple was not a chart smash, but Asher was so convinced of the artist's talent that he left Apple in 1970 and followed the American-born Taylor back to the States. It was a bold but wise move: Taylor signed to Warner Brothers, and Asher became his manager and producer. The two turned out an unbroken string of hit albums during the '70s and '80s. (Asher would also become crucial to shaping Linda Ronstadt's career; in addition, he produced albums by Bonnie Raitt, Cher and 10,000 Maniacs, among many others.)

Now a partner in Strategic Artist Management, Asher recently reunited with James Taylor to produce the artist's Live At The Troubadour album, with Carole King and Taylor's original backing band. During a bright and early morning in Malibu, California, Asher sat down with MusicRadar to discuss his short-lived heyday at Apple and what it was like to work for The Beatles.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

It's interesting: Paul McCartney wrote your first hit, A World Without Love, and he went out with your sister Jane. And yet, after he and Jane broke up, there must have been no hard feelings on his part - he made you head of Apple's A&R department.

"No, there were no hard feelings or anything like that. Paul and I had become good friends. Actually, when The Beatles weren't on the road, he used to stay at our house on Wimpole Street. He pretty much moved into the top floor, really.

"When he moved into his own house on Cavendish Avenue in St John's Wood, our friendship continued. We always got along very well. I'm very bad at dates and the chronology of how everything happened, but when Paul and Jane split up, he and I were fine. I can't remember what stage Apple was at that the time, of course."

So you were a pop star in your own right as part of Peter And Gordon. How did you come to be part of the Apple organisation?

"Here's how it all happened: Gordon and I didn't 'split up' as such; we just gradually stopped working together. Gordon wanted to make records on his own, and I started getting more and more interested in record production. The term 'split up' when it comes to pop stars usually implies some sort of Everly Brothers-type feuding, which wasn't the case with us at all.

"I had already started producing records. The first album I did was for Paul Jones from the group Manfred Mann. He was an absolutely fantastic singer and one of the best harmonica players in the world. Paul McCartney was aware of my interest in producing and the business side of the record making, so we would spend long evenings at his house on Cavendish Avenue discussing the Apple scenario, what it should be like, how things should work. It was a Beatles venture, but it was largely Paul's idea.

"I remember sitting with Paul and watching him draw diagrams of what Apple should be, what it should accomplish. Of course, the idea was that it should go beyond a record company, that it should be an arts endeavour in general. We wanted to allow people the chance to do what they wanted to do without going through corporate hoops - that was the concept.

"Anyway, during the course of those conversations, Paul said, 'You should produce some records for Apple. You should be part of this.' And I said, 'Great.' As things became closer to reality, he then said, 'You should be head of A & R.' They had already hired a proper American businessman to run the label, which was Ron Kass, who was great. So everything sounded terrific, and I was thrilled to be part of it."

What was the structure of Apple as a label? Did you have an actual A & R department? Did you have weekly meetings?

"The structure was loose, very vague. Ron Kass was the boss, but he reported to The Beatles, as we all did. They were the board of directors. Then there were various departments, like marketing and promotion and all those people who were in charge of getting the records made and put out. And a lot of it consisted of relating to our distributors, EMI and Capitol, who were on their best behaviour because they were dealing with The Beatles."

As head of A&R, did you have carte blanche to sign whatever you wanted, or did The Beatles have to approve of each act you brought in?

"I made it clear from the beginning that if I found something I loved and wanted to sign, that I would be allowed to do so. I don't know if that was in my contract…Come to think of it, I don't remember if I even had a contract! [laughs] So it wasn't like nowadays, where every little thing is spelled out. But I do remember saying to Paul, 'I assume that if I find something I love, just as if The Beatles find something they love, whether individually or collectively, that I can sign it.' And he said, 'Yes, absolutely.' So when I found James Taylor, I knew I could jump immediately and it wouldn't take months and months to get him signed up. I was also very confident that everyone would like him, as well.

"Those issues were very flexible. The A&R structure, however, being that it was very loose and was intended to have a sort of open submission policy was akin to opening up the Gates of Hell. The deluge of stuff that came in was, as you imagine, enormous."

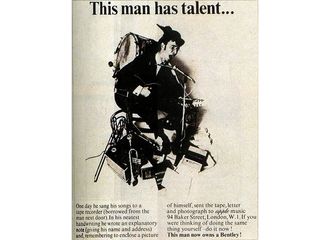

I remember seeing pictures of an ad Apple had run asking for submissions…

"Oh, the famous ad, right! It was a photo of a one-man band, with the copy sort of saying, 'Bring us your old, your tired and huddled cassettes' and stuff like that."

And it said at the bottom, "This man now owns a Bentley!"

"Oh, right. [sighs] It brought about total chaos. I'm not saying the process was chaotic, just the quantity of what came in. Apple was The Beatles, so obviously we were inviting trouble. I had a few people working for me up on my top floor, and sacks and sacks of cassettes and reel-to-reels would come in each day for them to listen to. I just thank God we didn't have MP3s back then; otherwise, the place would have exploded! [laughs]

"Everything got listened to, and if it was any good it was brought to my attention. Anything that I thought was interesting or funny or curious or even good - which, unfortunately, most of it wasn't - I then brought to The Beatles attention at our A&R meetings, which we held as often as possible with as many Beatles that could be bothered to turn up."

Now, [guitarist and producer] Danny Kortchmar brought James Taylor to your attention. And then you played a tape for Paul?

"My recollection is, I played a tape for Paul, yes. Danny had given James my phone number - he didn't directly bring him to my attention. I had become friends with Danny because his old band played with Peter and Gordon. And he and James were childhood friends. So that was the connection there.

"Anyway, James came over to London, played me his tape, and I loved it. He played me a couple of songs live, I loved 'em, and that's when I said, 'It just so happens that I've got this new job…' I don't remember the exact occasion, but I'm pretty sure I played James' tape for Paul at Paul's house. Paul definitely liked it, and I said, 'Yeah, I think he's the real thing." So Paul said, 'Sure, sign him.' And we proceeded to do so, quite quickly."

In listening back to the reissue of Jame's debut album, it's remarkable how fully formed an artist he was even then. He didn't seem to have to find 'find his voice' over a succession of albums - it was all right there.

"Oh yeah, he had his whole sound and identity from the word go. Something In The Way She Moves alone is worth the price of admission - and it was all on his demo tape. Some of them, like Carolina In My Mind, he wrote a little later on. But yes, he had been writing songs for some time and had developed this unique singing style and guitar style, which combined everything from Ray Charles to Segovia to…I don't know what. As you can imagine, I was inordinately impressed when I first heard him.

"You know, most artists, when they're really good, they start off good. The first Beatles record…it's pretty fucking good! Or Fingertips by Stevie Wonder, so many...Most of the time, if the artist is really world-class, there's something there right at the start."

Part of the fold-out jacket of James Taylor's 1968 Apple Records debut.

Paul and George Harrison appeared on Carolina In My Mind -

"Paul played bass on it, for sure. I'm told that George sang on it…I'm not sure. I think James has said that George is on the track, but I don't know. I hear James and me singing on it, but George…I don't know. I can't be certain."

Well, obviously, George was impressed by James Taylor - he used the line Something In The Way She Moves for his song Something.

"Oh, yes. He definitely took a liking to that lyric. [laughs] Whether that line would have wound up in George's song were it not for James Taylor, I have no idea. I'm sure George was working on a song called Something…You know, we're talking about two genius songwriters, so who knows?"

Paul and George were fans, but what did John and Ringo - did they have an opinion of James Taylor?

"Ringo liked him, I think. As far as I can remember, he expressed approval. As for John, he was pretty much involved in whatever he and Yoko were doing at the time. I don't recall John's opinion on James or Mary Hopkin or any of the other Apple artists at the time. I think he was off in 'Yoko world' a bit."

Speaking of Mary Hopkin, were you involved with her career at Apple, or was she strictly a Paul project?

"I was involved, but she was a Paul project. She was on this TV show called Opportunity Knocks, and our friend Twiggy called Paul and said, 'You must turn on the television.' As it turned out, we missed her, but we caught her the following week and were knocked out. Derek Taylor and I went to sign her and Paul produced her and I assisted him."

Did you have the feeling that Those Were The Days could be a hit?

"As much as you're supposed to say, 'No, I had no idea,' yes, I absolutely knew that Those Were The Days could be a hit. Paul knew the song he wanted to do before we even signed her. He had the song in mind, he had the arrangement; he's a genius and one of the greatest record producers ever. I knew it would be a hit. Everybody sang along with it, everybody loved it - it felt like a song you knew before you even heard it. It was a one-of-a-kind thing."

Now, after you left Apple, you followed James Taylor back to America where he became something of the forerunner of the California soft-rock scene.

"Yes, I became his manager then. It was funny: they put him on the cover of Time magazine as 'Rock's New Soft And Low' or something. The only thing James would take issue was the California connection. He never lived there; he only went there to make records. So it was a bit strange to be associated with a state he didn't visit much or didn't like much."

I realize this is hindsight, but when you signed James, did you have any inkling of how far he could go?

"No, not at all. I mean, you can see talent in front of you, but you never really can tell. I think at that stage, when I signed him, we were just hoping to sell out the folk clubs. If we could fill The Bitter End in New York or The Troubadour in LA, and then play colleges and stuff, that was where we were headed. World domination was not on our agenda. I mean, I thought he was that good. I thought that everybody should like him. But you never know. That's just the way it happens."

The breakup of The Beatles was, of course, quite messy. But what about the collapse of Apple at the time? What do you recall of its last days?

"See, I wasn't around all of that. I resigned right around the time that Allen Klein arrived to be the label manager."

The two of you didn't get along?

"It wasn't so much that. I had spent some time in New York and knew of his reputation. I'd heard a lot about him and knew people who'd worked for him. I just didn't think he was the right man for the job, that's all. The Rolling Stones were already wary of him, so I didn't think he'd work for The Beatles. But the final collapse of Apple, I wasn't around for that. The decision to leave wasn't that difficult, really. James Taylor had already decided that he wanted to go back to America, and since I was a firm believer in his talents and was going to be his manager, I decided to take the gamble and go to the States, as well."

When you listen back to the original James Taylor album from 1968, what memories come flooding back?

Peter Asher in 2009, arriving to launch BritWeek in Los Angeles. © Frank Trapper/Corbis

"Oh, I think it's a little too produced, to be quite honest. I think I put too much stuff on there. I didn't want people to go, 'Oh, another American folkie.' So I think, in retrospect, I went a little overboard. Later on, when we did Sweet Baby James, we went the other way and made it more of a stripped-down record, which really made the songs and the power of James' voice stand out."

How about some of the other Apple signings, such as Badfinger, were you involved with them?

"To some degrees. One of the strangest things I discovered recently was that I took the photo for one of the Badfinger albums. I don't remember it, but I guess I was involved in a multitude of ways. It was quite a time. Some projects carried on with me not having to do too much, while other things I had to keep on eye on. Standard record company stuff, I imagine."

Do you think that the plugged got pulled on Apple Records prematurely? Do you think it could have gone on a little longer?

"If The Beatles were all getting along, I suppose it could have. But that's like saying, 'The Beatles would still have been together.' The situation went up, up, up and then it went down rather fast. But in retrospect, you tend to remember the good times mostly - the fun, the laughs, the craziness. It was a magical era, and I was very fortunate to be a part of it."

Liked This? Beatles Week on MusicRadar was our huge celebration of all things Fab Four and packed with interviews and features.

Connect with MusicRadar: viaTwitter, Facebook and YouTube

Get MusicRadar straight to your inbox: Sign up for the free weekly newsletter

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.

"It may have bothered him that people didn’t recognise his guitar virtuosity, which might be why the song devotes so much space to his shredding": A music professor breaks down the theory behind Prince's When Doves Cry

“It didn’t even represent what we were doing. Even the guitar solo has no business being in that song”: Gwen Stefani on the No Doubt song that “changed everything” after it became their biggest hit

Most Popular