Nils Lofgren talks guitars, Springsteen, Neil Young and box set Face The Music

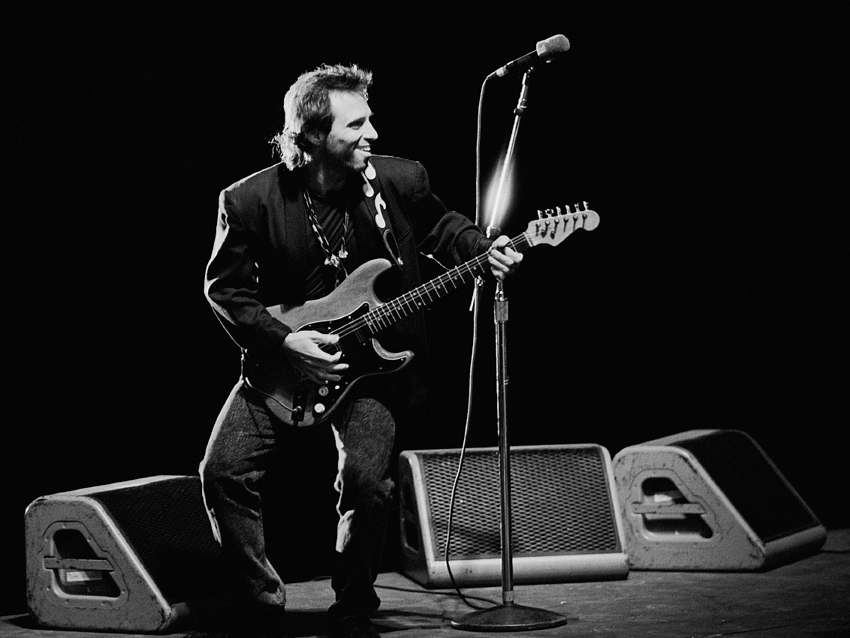

Come June, guitarist Nils Lofgren begins his fourth decade as a member of the E Street Band. But for the millions of fans who have come to know the versatile, multi-talented musician (and recent Rock and Roll Hall of Fame inductee) for his long tenure with The Boss, there is also a loyal group of record buyers who have followed Lofgren since his days fronting his own band Grin in the early '70s.

For those fans, the upcoming 10-disc box set Face The Music, due out May 27 from the Concord Music Group, will prove a treasure trove. On nine CDs and one concert DVD, the meticulously annotated collection traces Lofgren's rich musical life and times, starting with his pre-Grin band Paul Dowell and the Dolphin to his work with Neil Young and Crazy Horse and throughout his solo career up to his latest full-length effort, 2011's Old School. Two of the discs contain 40 previously unreleased tracks and rare gems.

As much as he relished the opportunity to flip through his back pages, Lofgren admits that retrospection isn't his usual default mode. “It's not like I've haven’t forgotten what I’ve done," he says, "but because I’m so focused on being in the E Street Band and the other things I’m doing, I don’t dwell on the past. I’m always like, ‘What’s my next solo record?’ Old School is one of the best albums I've ever made. I’m as proud of that record as anything I’ve done."

For all his skills as a multi-threat singer, songwriter, ace guitarist and keyboard player, and despite a string of critically acclaimed albums, hit singles always eluded Lofgren. "You learn to put it all in perspective, and you keep going," he says softly. "There are a lot of tracks through the years that could have gotten more exposure at radio, but for whatever reason, the stars didn’t align for that heavy rotation. But even then, I was more focused on what was next for me. I still am that way. The dream is still there.”

Lofgren sat down with MusicRadar recently to talk about Face The Music and some of the legendary names that have figured into his remarkable career. (You can pre-order Face The Music at Amazon.)

Were you surprised when Concord approached you to put together the box set?

“I was, yeah. It was a big surprise. For decades I had gone to the old companies – I owned them money because I didn’t have any hit records. I offered them five dollars a CD to buy my old music, just to sell on my website and make it available. They’d always say no, even though it costs a buck and a quarter to make a CD. It’s not a unique story. If you don’t have big hit records in your career, your old stuff can become extinct.

“Psychologically, that was crushing, but I had to get over it. So I was resigned to the situation – it was what it was. But about sixteen months ago, Concord came to me with the idea of doing a box set. They seemed really into it, which was great. The more I got into it, the more I felt like we should do it right and make it comprehensive with the bonus tracks. To be able to hand-pick the material and know that it was going to see the light of day, it was very powerful for me. We turned it into what it should be: a massive, 45-year retrospective. They gave me a couple of great art directors to work with. My wife, Amy, and our assistant, Omar, pretty much turned our home into a work station for this project for over a year and a half.”

Writing Keith Don't Go

The fact that you didn’t have big hits but kept making records could have only happened in the ‘70s. Nowadays, a label would have pulled the plug after one album.

“That’s true. When I came up, if they happened to like you, they gave you more than one shot. That’s certainly not the case anymore; it’s very disposable. I was lucky to work with some great executives, in particular Clive Davis, who signed us Spindizzy/Columbia first. I worked David Briggs, Neil Young’s producer. And then, of course, I spent many years at A&M with Herb Alpert and Jerry Moss, who were both great, Jerry in particular. But you’re right: I started at a time where I was able to make a lot of music without that massive hit that’s required these days for it to kick into that second or third album.”

Were your old tapes in good shape? Did you have to bake any of them or do any kind of restoration?

“Billy Wolf from Wolf Productions in Arlington, Virginia, is mastering the whole thing. He’s worked with me for 20 years or more. He had to bake some stuff. Of the old tapes, some of them were useable, some weren’t. But Billy has a lot of tricks up his sleeve, and he’s got great ears. Some of the things were on basement cassettes, but rather than not use them, baked or heated or treated somehow, we got them to where they had to be. To me, we had to share certain things no matter what.”

Were there any songs or performances that surprised you? Were you ever like, “Oh, I forgot we did that.”?

“Yeah, there was a lot of stuff. I got very thorough in digging through tapes; I went on a lot of fishing expeditions for things that I felt needed to be included. Billy Wolf and I would spend hours and hours pouring over tapes; some of them were useless, but there were some real gems, too. I was desperately trying to find a cassette tape of Keith Don’t Go that I did with Grin and Neil Young – he played piano and sang on it. I went through thousands of cassettes in my home in Arizona and back in Maryland – I’ve got a place out here to tour the East. But we struck gold when we discovered the actual 16-track master. We got to remix it in the same studio and with the same engineer who worked with Briggs and Grin, but obviously we made it what it should have been, not just a primitive rough mix.”

It’s interesting that you recorded that song in ’73 with Neil on it, but you recorded it again and put it on your debut solo record two years later.

“On the ‘Fat Man Album,’ right. I had written it on the Tonight’s The Night tour. I was with Neil Young in England and was meeting a lot of people who claimed to be Keith’s best friend. I took that with a grain of salt. The recurring theme with everybody was how worried they were about Keith’s health. I thought anybody who had just done Exile On Main St. couldn’t be that bad off – I was naïve and young. But I had this dark, ominous piece of music, and I put the two concepts together. The idea was to write giant thank-you note on behalf of all the fans, like, ‘Take care of yourself, Keith, for our sake and for yours.’”

Hooking up with Neil Young

I’m curious – has Keith ever spoken to you about the song?

“No. In fact, I don’t know if he’s ever heard it. I just don’t know. I mean, I know that he knows I wrote a song about him. I’ve met him at shows – he’s always been very friendly. At a show in LA he saw me playing ping-pong, and he gave me a big hug. He yelled at a photographer to come over and take a picture of us. He said to the guy, ‘Make sure Nils gets a copy of that.’ We put it in the booklet.

“But as for the song, a friend of mine, Don Marrandino, a GM in Vegas who was running the Hard Rock, asked Keith about it, and he said he hadn’t heard it. Don asked him why, and you know, Keith jokes a lot, and I guess he said, ‘Because I don’t wanna go.’ [Laughs] Maybe if he heard the song it would give him ideas. I thought that was pretty funny. Maybe it’s the truth. Who knows?”

You included the song Beggar’s Day, which you wrote for your onetime Crazy Horse bandmate Danny Whitten.

“That’s right. Danny was great. I first met him in ’68 at the Cellar Door on the first Crazy Horse tour. I got to befriend them through Neil. I was out in LA three weeks later, and I got to know all of them. Danny would drive me around and talk. He was charming, a roughneck surfer-type guy with dirty, sandy hair and a chiseled faced – very sweet temperament. He was a genius-gifted singer and player and a pretty strong, hearty guy.

“Over the years, the drugs and alcohol took a toll on him. By the time we made the Crazy Horse album – with Jack Nitzsche producing and joining the band on keys, and me as a guitarist and writing a couple of numbers – Danny was playing and singing great, but he wasn’t good for too much else. I’d tune his guitar for him and get him ready to go. We finished the record and he came back East. At one point, he was considering joining my band Grin. Tragically, he just wasn’t up for it physically. We did Tonight’s The Night as a wake album for Danny and for [Young roadie and friend] Bruce Berry, both of whom had succumbed to drugs and alcohol. It was dark and healing in a strange way.”

You hooked up with Neil when you were so young. What were you, 17?

“Well, I had just hit the road with Grin. We were auditioning for producers in New York City and were headed to LA. I’d go backstage and ask for advice, because I didn’t know anything about the business. Some people talked to me, some didn’t. Neil talked to me, gave me his guitar, let me sing, bought me a cheeseburger and a Coke for four shows over two nights. He’d call me from the road, told me to look him up in LA, which I did. He turned us on to his producer, David Briggs, and took us under his wing, moved us into his home in Topanga. He really helped so much. He told me ‘Your band is really good, but you need a better bass player.’ So we got one, Bob Gordon, and we were ready to record.”

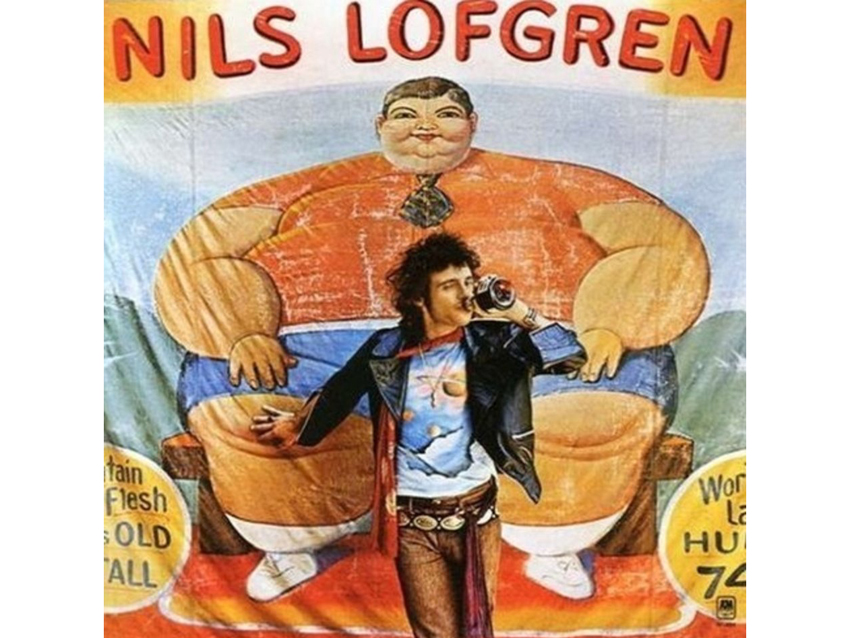

Working with photographer Ed Caraeff on the 1975 "Fat Man" album cover

Neil’s guitar style is so idiosyncratic. How did you go about working out your guitar parts to compliment what he did?

“Well, mostly he wanted me on piano for things like Southern Man and Cripple Creek Ferry… Only Love Can Break Your Heart and Don’t Let It Bring You Down. On Tell Me Why he moved me over to guitar. I didn’t own one, so he loaned me a great old Martin of his that he eventually gave me. On Till The Morning Comes, he was on piano and I played guitar. I sang on most of it with Ralphy [Molina]. It was just a natural thing. I was a very simple piano player, but because of my accordion background, Neil and Briggs felt that I could figure out some simple parts. You’ve got a very colorful Greg Reeves playing some solid James Jamerson bass parts, then Neil on top and me and Ralphy being very simple in the middle – it had a nice vibe to it.”

You've played with Neil a couple of times after going solo. Has there always been an open-door policy with him?

“No, but I wish there was – I’d be with him a lot more. I’d go see him play, and I’d stay in touch with all the guys – still do. We did the Trans album and then the tour, six weeks of stadiums in Europe. Then in the mid-‘90s we did MTV Unplugged. Last year, we did MusicCares, where as an alumni I played Born In the USA on keyboards as Crazy Horse performed. We were honoring Bruce. I think that’s out now on DVD – I’ve gotta get it. But yeah, if there were an open-door policy, I’d show up a lot more.”

The “Fat Man” circus painting behind you on your 1975 solo debut is now an iconic album cover. How did that come about?

“It was a beautiful accident. [Photographer] Ed Caraeff had planned a 10am session. I don’t like photo sessions – I’m just not good at them. I headed off with this colorful outfit on, but I had no idea what we were going to do. I showed up at Ed's door with this outfit on and a bottle of Grand Marnier. He looked at me and said, 'Oh, my God, these colors remind me of something.' In his backyard he had this giant antique poster from the ‘20s of what was at the time the fattest man alive. It matched my outfit, so I stood in front of it. Just like that, it had a cool vibe. I sipped from the bottle, and we got a great cover.”

Collaborating with Lou Reed

There are several songs on the box set that you wrote with Lou Reed. Did they come about because of Bob Ezrin, who produced you in 1979? Previously, he had worked with Lou.

“Yeah, Bob had a specific idea for that. I had some songs and was going to work on a lot of lyrics, but he said, ‘Why don’t we get some help from a master like Lou Reed?’ I thought that was a stretch, but we went by Lou’s studio and met with him. He was really friendly and said he was open to it, even though he hadn’t co-written before.

“I went to Lou’s apartment in Greenwich Village, and we spent a long night drinking and watching a football game. I was a big Redskin fan from DC and still am, and he liked the Dallas Cowboys. It was a Cowboys-Redskin game. We had a real healthy rivalry, two fans being really into it. But I can’t even tell you who won the game, which is a testament to how excited I was; the whole time I was thinking, ‘Is this gonna work? How are we gonna do this?’

“I had so many things written. I sent Lou a tape with of 13 songs with some lyrics, some half-lyrics, some titles and ideas, some with just some humming of the melodies. It was all up for being improved or replaced or altered, including the music. A month went by and I hadn’t heard from him. I was back in Garrett Park, Maryland, in a rental house. I was writing songs, improving songs, and I’d get together with Bob and go over what I’d done.

“Then one night Lou called me up at 4am. He woke me up and said, ‘Hey, I love this stuff. I’ve been up writing for three days and nights straight. I’ve completed 13 full sets of lyrics. Why don’t you put some coffee on, get a pad and paper and I’ll dictate them to you?’ So that’s what we did. I spent hours on the phone, being dictated 13 songs line by line by Lou Reed.

“I spent the next few days at this funky old upright and with my guitar, slowly and calmly putting Lou’s words to the music. Soon after that he said there were three of the things he wanted to use. Ezrin and I were fine with that; we used a few, and I’ve put out a few since then. Sadly, we lost Lou, which is a terrible loss, but I’m determined to go back and find the four or five other gems that no one’s ever heard and find a way to share them.”

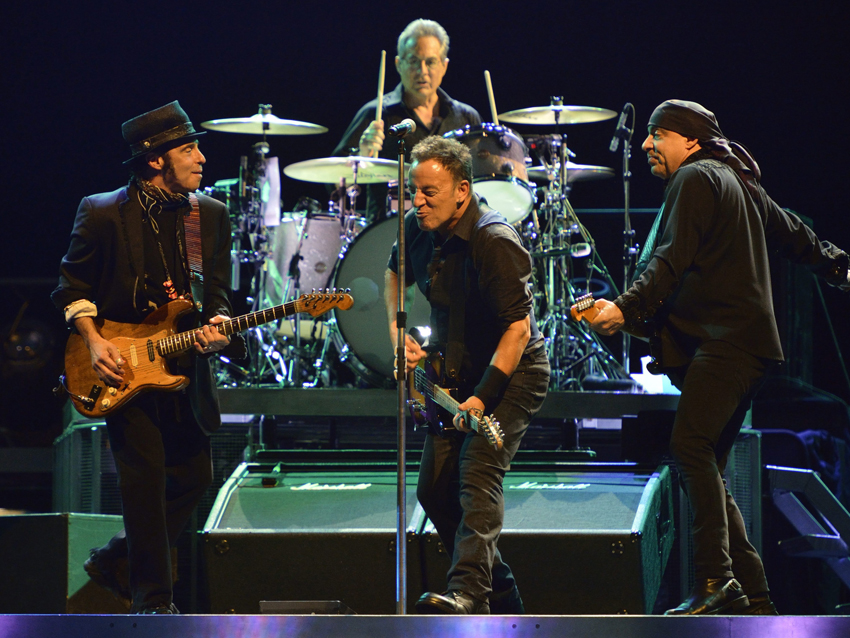

On Springsteen and Little Steven Van Zandt

Let me ask you about when you first joined the E Street Band. You had to learn an incredible of amount of material all at once, but how long did it take you to start putting your own imprint on the songs?

“It took a while. I got the job with the E Street Band a month before the opening night of the Born In The USA tour, so I didn’t have the time I would have wanted. That was nobody’s fault. So I did a cram course and got a ledger book of all the songs. There were all the chords, but there were also harmony parts, along with notes of where I'd stand and various ideas. It was just a place to start.

“I’d been to see the band throughout the ‘70s and ‘80s – I just really loved them. I didn’t worry about getting my own parts in there, though; I just wanted to cover the parts and lines and harmony parts that Steve [Van Zandt] did. Bruce got Patti [Scialfa] in the band to help with the higher harmonies that I couldn’t nail.

“You can’t replace Steve. He’s got his own sound and look, the way he sings and especially the way he plays. Bruce and Steve are like Mick and Keith, two rough R&B-types. They have that nailed. But initially, I just tried to cover those parts, and then once that was nailed I threw in my own little turns and ends and stuff. I just wanted to get the job done. I wasn’t worried about solos – I do a million solos in my own show. I love playing rhythm guitar, and of course, when Steve got back in the band it was a big plus. It was great to hear him sing those songs.”

It’s a big guitar army now with you, Bruce and Steve all on electrics – and sometimes Tom Morello is playing with the band.

“Yeah, once Steve came back in, and you’ve also got Patti playing rhythm all the time, we didn't need four guitar players in the band. I talked to Bruce about it, and then I went off and challenged myself a little bit. I learned pedal steel guitar, Dobro, bottleneck, lap steel, six-string banjo. Mike Auldridge in Silver Springs, Maryland, is a buddy of mine, and he’s one of the great Dobro players. He put some lessons on tape of Dobro and pedal steel. I took it on the road and got an old pedal steel from Larry Crabb, my buddy, who is Neil Young’s guitar tech. He helped me get going. Mark Muller, another great guitar player who was with Shania Twain, and another pedal steel guitarist in Jersey, gave me a crash lesson in mid-rehearsal. I just wanted to add some other sounds in the E Street toolbox.”

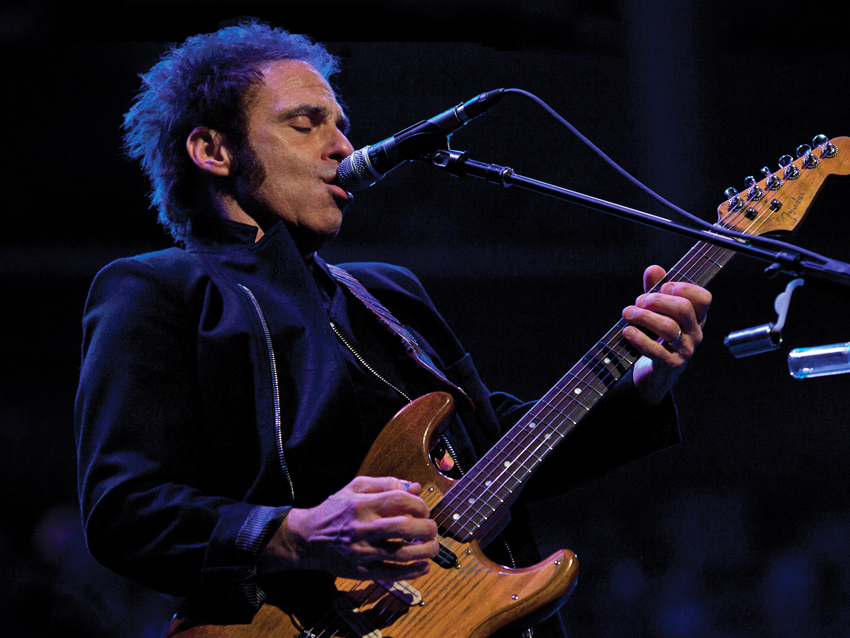

You have two ’61 Strats that you’ve always used, but are there any guitars that don’t work with the E Street sound? Bruce and Steve are usually on a Tele and a Strat…

“I wouldn’t say something won’t work, but to me it’s redundant to pick up another Tele or Strat. I picked up an old Jazzmaster that I have, and I put on the heaviest strings you can buy – they’re like boards. I found that was a nice sound, marrying the Strat and Tele with the Jazzmaster. I got a bunch of them because I have different tunings and capo positions for certain songs. Every time those two guys have those guitars on, a Jazzmaster with heavy strings adds a warmer electric sound that really marries their tones together in a nice way.”

Nils Lofgren talks guitars, Springsteen, Neil Young and box set Face The Music

It’s interesting that you picked a Jazzmaster. A lot of people might go for a Gibson, like a Les Paul.

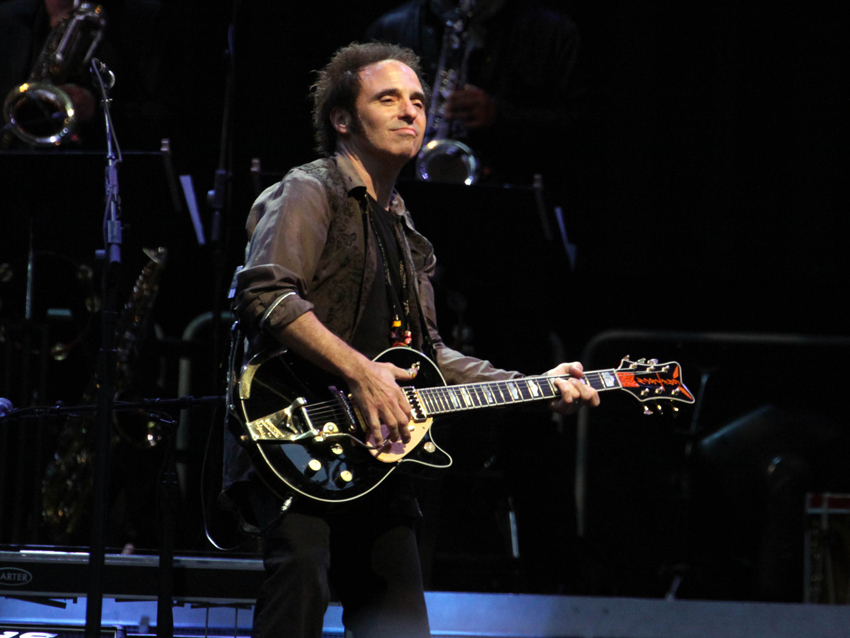

“I’ve got a lot of Gretsches that I play – Black Falcons and Black Penguins. I’ve also got a PRS with a wang bar. I do use other electrics. For the traditional hard rock thing, the Jazzmaster works for me. And there’s Takamine acoustics – six- and 12-strings. It’s a full array of guitars and sounds.”

I saw a picture of you with a Zemaitis guitar that was given to you by the wife of the late James Honeyman-Scott.

“That’s right. Jimmy was a dear friend. That was a horrible loss. After we buried him in a town outside of London, we had a luncheon and were commiserating. Peggy Sue, who is still friends with Amy and me – she still comes over and visits us once in a while in Arizona – she took me to the warehouse and said that I should pick out a guitar.

“I felt bad for her. It was a gloomy, rainy English day. I picked out a cheap, knock-off Strat – he had a bunch of ‘em – and she said, ‘No, I don’t want you to do that. I know what you’re doing. For me, I want you to pick the best guitar that you would play to remember Jimmy by.’ So I took the best guitar, the custom Zemaitis with his name engraved on the headstock. I use it to this day.”

James only got to do a couple of albums, but I’m convinced that if he had lived and made more recordings, he’d be recognized as one of the greats.

“I do, too. I got to sit in the the Pretenders in Baltimore and New York and Santa Barbara. I was living in LA at the time. Jimmy would come over, and we spent a lot of time bar-hopping and jamming in hotel rooms. I loved everything about him. He was just a sweet soul. It was such a horrific phone call to get when we lost Jimmy.”

[Bassist] “Pete [Farndon] died a short time after James. Was there ever any talk of you joining the Pretenders?

“I mean, I didn’t think that. Amongst ourselves, Jimmy and I would debate about me as a guitar player and a keyboard player. He would be like, ‘I’m like the heavy. It would be great to have another guitar player to work off of.’ I was like, ‘Yeah, and I could be a keyboard player, too.’ We never took it to the band and lobbied for it; it was just an idea that he and I had that it would be great to work together inside the Pretenders. He knew I loved the band. But it was just good-natured talk.”

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.

“I’m beyond excited to introduce the next evolution of the MT15”: PRS announces refresh of tube amp lineup with the all-new Archon Classic and a high-gain power-up for the Mark Tremonti lunchbox head

“These guitars travel around the world and they need to be road ready”: Jackson gives Misha Mansoor’s Juggernaut a new lick of paint, an ebony fingerboard and upgrades to stainless steel frets in signature model refresh

“I’m beyond excited to introduce the next evolution of the MT15”: PRS announces refresh of tube amp lineup with the all-new Archon Classic and a high-gain power-up for the Mark Tremonti lunchbox head

“These guitars travel around the world and they need to be road ready”: Jackson gives Misha Mansoor’s Juggernaut a new lick of paint, an ebony fingerboard and upgrades to stainless steel frets in signature model refresh