Music legend Alice Cooper talks about 12 career-defining records

“When we came out, people had a hard time defining us," says Alice Cooper, referring to his original band, although he could just as easily be talking about the glam-ghoul comic-book villain that the former Vincent Furnier assumed in the late '60s. "At that time, everything was peace and love, everything was beautiful, and along comes Alice Cooper to drive a stake through the love generation."

Cooper arrived in Los Angeles from Phoenix in 1967, along with his mates Glen Buxton (guitar), Michael Bruce (guitar), Dennis Dunaway (bass) and Neal Smith (drums). At first they were The Spiders and then The Nazz before they realized that Todd Rundgren already owned that name. Assuming the titular role of Alice Cooper proved to be a canny move, one that flew in the face of everything the singer saw when he looked around at the Los Angeles music scene of the time.

"Everybody had this whole attitude of ‘We’re not really in it for the money. We’re in it for the art,'" he remembers. "And we were going, ‘Really? Why?’ We were all about glamour – Ferraris, big houses. We acted like rock stars. We were rock stars before we were rock stars. The only other guy who did that was Bowie."

The term "shock rock" was coined in response to Cooper's groundbreaking, elaborate gothic-horror/vaudeville stage show, one which included everything from guillotines to electric chairs to beheaded baby dolls. Merging elements of horror movies with rock came naturally to Cooper, who drew on sensibilities both terrifying and comedic. "I looked around, and I saw a lot of Peter Pans but no Captain Hook," he says. "There were a lot of rock bands that were my heroes, but not one had my favorite villain. I saw an opening. I decided to create Alice as this villain – sleek, dark and clever."

Musically, the band rocked with the same kind of raw, proto-punk force that was coming from groups like The Stooges and the MC5, but Cooper admits that their biggest influences were British. "We idolized The Beatles and The Rolling Stones," he says. "As for our sound, we wanted to be as close to the Yardbirds as we could. We loved Jeff Beck’s guitar style and the Having A Rave Up album the band did. We looked at that and said, ‘That’s really good. Now, what if we did that with our lyrics and better melody lines?’ If we could have that musical flavor with our attitude, I thought it could be unique."

The band's first two releases, 1969's Pretties For You and 1970's Easy Action, failed to catch on with the public, but starting in 1971, Cooper began a collaboration with a newbie producer, Bob Ezrin, that would deliver hit after hit over the years. "Everything changed when we started working with Bob," Cooper says. "He wouldn’t let us put any filler on an album. He wanted every song to be either really unique or really cool. Even the songs that weren’t radio hits were still done in a way to break new ground. We never sacrificed a track. Every spot on a record was special to us, and that came from Bob.”

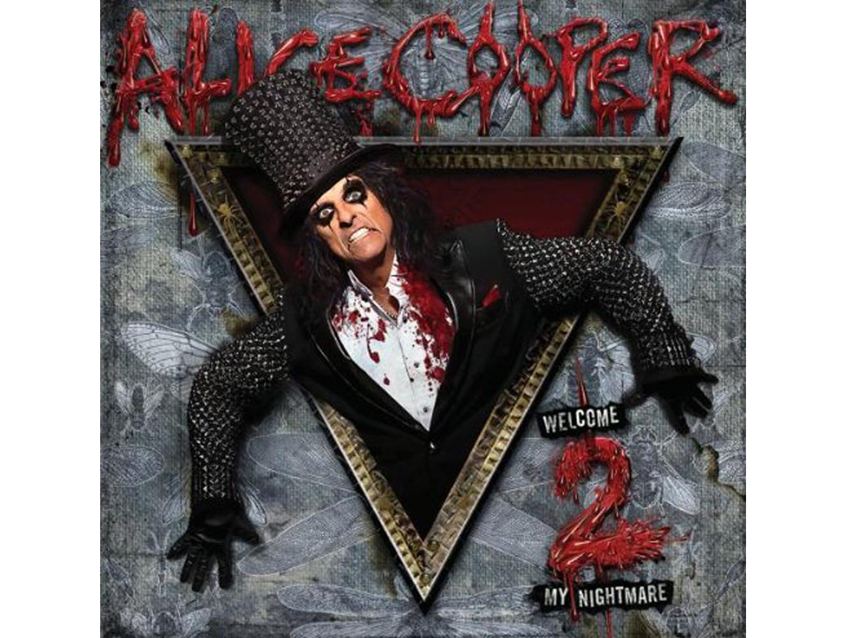

In 2011, Cooper reunited with Ezrin for his strongest set in years, Welcome 2 My Nightmare, and the two have another one in the bag for next year, a covers collection in which the singer pays tribute to the likes of The Who, The Doors, John Lennon, Harry Nilsson and Jimi Hendrix, among others. MusicRadar recently sat down with Cooper to talk about a dozen albums that we deemed "career-defining." While the Godfather of Shock Rock didn't take issue with any our choices, he did note that "my records are like my children – I love them all."

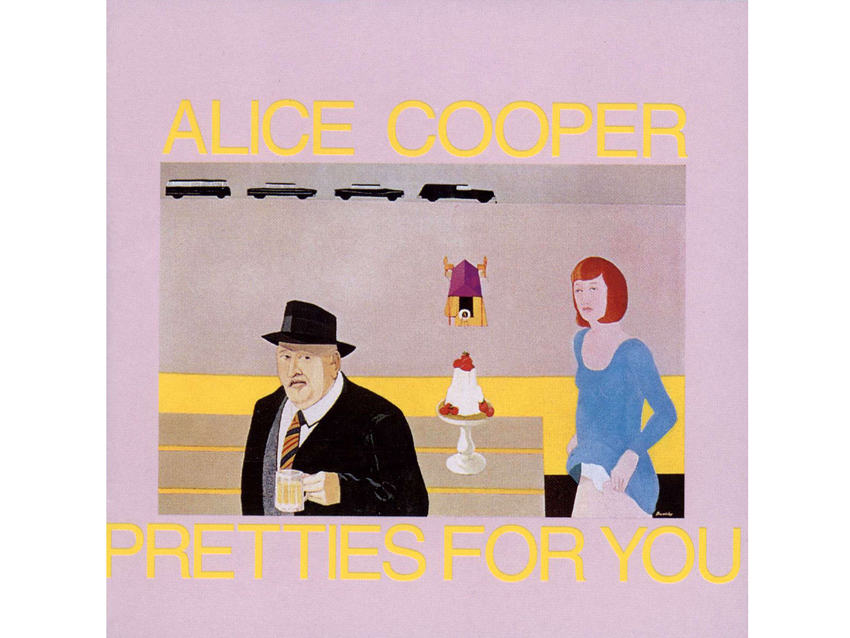

Pretties For You (1969)

“I never thought that Pretties For You or Easy Action were Alice Cooper albums. We were The Nazz, until we found out that Todd Rundgren had a band by that name. We had been playing at the Cheetah Club in LA as The Nazz. All of these songs were written when we called ourselves that.

“On these early albums, we sat and listened to West Side Story, Stockhausen, The Yardbirds, Sandy Bull – all kinds of strange and different things. We put it all together into songs that were two and a half minutes long, or even two minutes long, with 28 changes in them. It was complicated, but it had pretty little melody lines; it went here and it went there, but it never came back to the original thing.

“When Frank Zappa [who signed the band to his Straight label] heard us do this stuff live in his basement, at the Log Cabin, he went, ‘Alice, I don’t get it. What is this?’ [Laughs] I said, ‘I don’t know, it’s just the way we write. Does that mean you don’t want us?’ He said, ‘No, no. I almost have to record you, ‘cause I don’t get it.’ He asked me where we were from, and when I told him Phoenix, he said, ‘I thought you were from London or somewhere like that. You have snakes and guillotines, and you’re from Phoenix? Now I really don’t get it.’

“Nobody wanted us at the time – they wanted the next Creedence. Frank said that he didn’t think people would believe that we could play our songs live, and for that reason, he wanted to record everything live. ‘Just do live recordings of these songs. We’ll take the best versions of everything,’ he said. It was interesting."

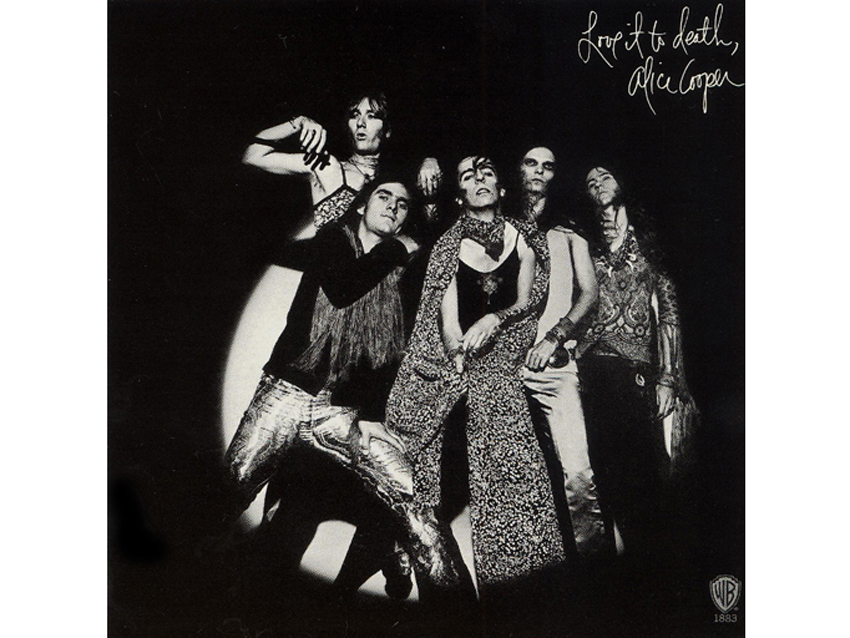

Love It To Death (1971)

“When Bob Ezrin got a hold of us, he said, ‘When a Doors record comes on, you know it’s Jim Morrison singing, and you know it’s Robby Krieger and Ray Manzarek and John Densmore playing. They have a signature sound. People love you guys, but for all anyone knows, you could be the Electric Prunes. What we’re going to do is work on your vocals, so that when people hear this music, they know it’s Alice Cooper.’

“We were a stubborn group of guys who didn’t want to listen to anybody, including Frank Zappa. Bob Ezrin jeopardized his job to produce us, and we, for the first time – don’t ask me how or why – believed in him, even tough he had never produced before.

“He came in and we played I’m Eighteen, and he said, ‘Too smart. It needs to be dumber.’ So we’d go back and work on it, and he’d again say, ‘No, still too smart. Dumb it down.’ Finally, we got down to just ‘dun-dun-da-da-da-da-duhnn!’ It was so powerful and in your face.

“Originally, he thought the song was called I’m Edgy, and I thought that might make a better title. He said, ‘I’m Eighteen – every kid in the world will relate to that.’ But he was insistent on us dumbing it down. We did question that approach at first, because we wanted to be The Yardbirds. But there was something about his attitude that endeared him to us.

“He’d say, ‘That bass part? I’m gonna put a cello under there.’ We looked at each other and said, ‘Not on our record you’re not.’ I thought he wanted to make it like Yesterday or something. He said, ‘Let me just play it for you.’ He put cello and piano on it, and you couldn’t tell what it was, but it sounded rich and cool and not normal. He was solidifying the bass and guitar parts with other instruments, and it really made the song pop. That right there made us go, ‘How did he do it? He’s right!’ From then on in, we trusted him with everything.”

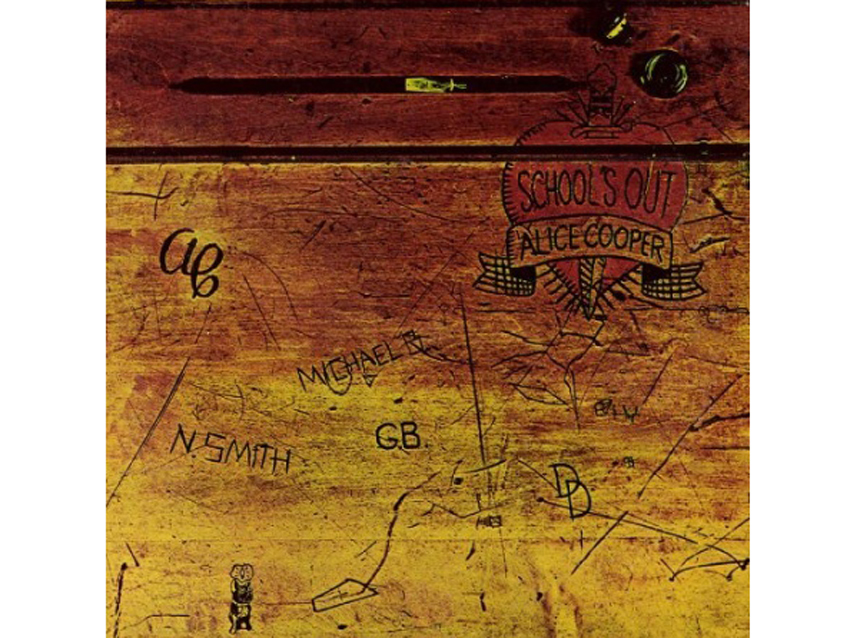

School's Out (1972)

“We got such good reviews on Love It To Death. It’s sort of like when your first album comes out and everybody loves it. For the next one, everybody says, ‘The next one’s gonna suck. Now we’ll see what they’re really made of.’

“Killer was bigger than Love It To Death. To a lot of the critics, it was the best album of that year, so it showed some progression as to where the band was going. We were a better band, absolutely. At that point, Bob Ezrin said, ‘Let’s go for the fence here.’ So we stretched a little more and put a little more West Side Story in. Our band was not as much influenced by the blues as we were by West Side Story and Guys And Dolls, James Bond and horror movies. We didn’t mind that seeping into our music.

“As much as we watched James Bond movies, I always loved listening to the soundtrack albums, the John Barry stuff. I’d say, ‘Listen to this section here. What would that sound like with guitars?’ When we did Halo Of Flies, there were three different spy themes going on in at once. That became part of who were were.

“I didn’t mind doing the Jets song. Again, it’s what we were. You know, in a lot of kids’ cases, we were the closest thing they’d ever get to seeing a play or something on Broadway. I thought putting West Side Story in would inspire people – you know, ‘What is this thing they’re doing?’ In the era we were in, that was a really big deal, and we thought it was cool.

“With the song School’s Out, I remember Glen Buxton – the late, great Glen Buxton – just played that riff one night. It was a very bratty riff, almost like him going ‘nah-nah-nah-nah’ on the guitar. He was like an encyclopedia of trivia for shows like Dobie Gillis and Leave It To Beaver. You could ask him anything about one of those shows, and he’d know it all. So him doing that ‘nah-nah-nah-nah’ thing on the guitar almost sounded like a character on one of those shows.

“It’s interesting to think, ‘What’s an anthem?’ And the answer is, an anthem is a song that everybody can agree on. It speaks to kids everywhere. Now, what’s more anthemic than hating school? School’s out – there you go. When we did that song, it was the only time I told Bob Ezrin, ‘If this isn’t a hit, I might as well start selling shoes.’

“Every part of that song was on the money. And we got in The Yardbirds, too – that Bolero bit. Bob knew how to put all of that in a package and really make it work. Then, when we came up with the line ‘Got no class, got no principal, got no innocence, I can’t even think of a word that rhymes,’ that was the line that drove the stake through it.”

“And the cool thing is... it’s a good hard rock song. It wasn’t just a theme – it really rocked.”

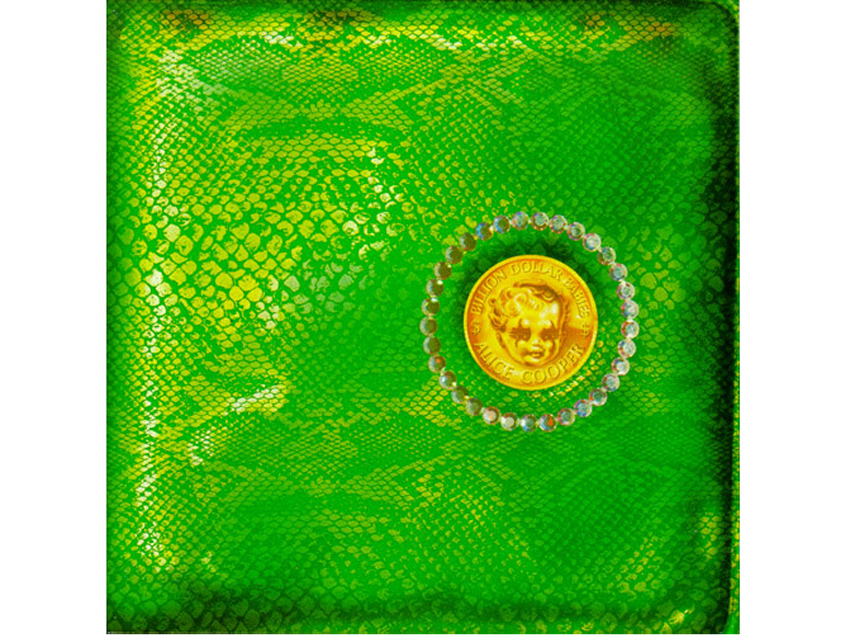

Billion Dollar Babies (1973)

“We were doing two albums a year. We were on the road constantly, we didn’t live anywhere, and we were always writing. By the time a tour was over, we’d have two weeks to put all of our material together and say, ‘OK, what do we have?’

“Bob Ezrin was our George Martin. He would listen to it all and start putting it into forms. Touring was easy compared to working in the studio. Bob would be very tough on us. We spent hundreds of hours in the studio, getting things right, making sure there was no filler. And there was nothing on the records that we couldn't play live.

“On Pretties For You, we had a great germ, the song Reflected. Bob heard that and said, ‘I hate to let that song just go away. Why don’t we reconstruct it?’ We had the idea of it – it was the ’72 elections, and Nixon was just hated by everybody. Who better to run against Nixon than Alice Cooper, the scourge of rock ‘n’ roll? I was Marilyn Manson times 10. So it became Elected, the perfect satire. Musically, I always saw it as our tip of the hat to The Who.

“The song went to number one in England, just like School’s Out did. It was great that England was sort of our engine. Everything we put out there went right to the top. Billion Dollar Babies, the album, hit number one in the UK and number one in the States, so we were feeling good.”

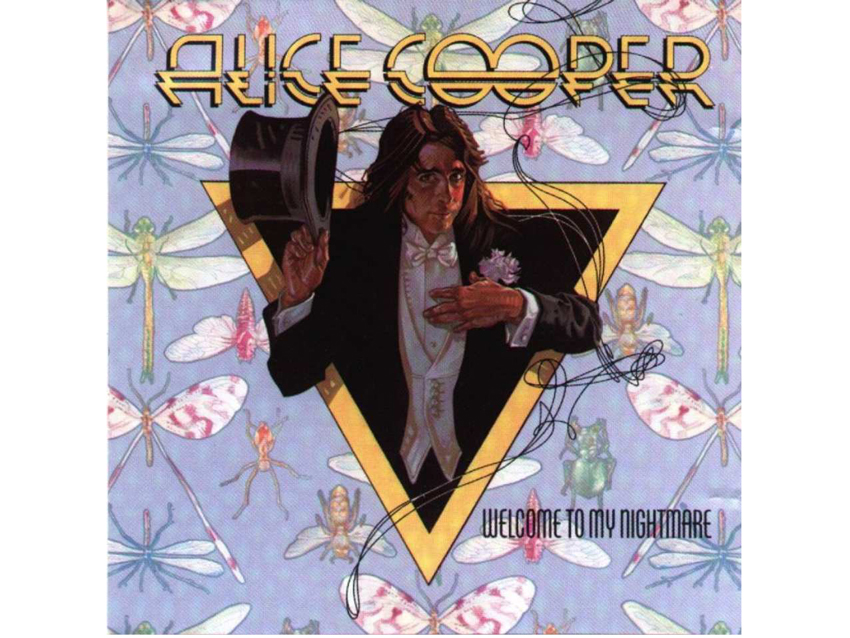

Welcome To My Nightmare (1975)

“My first solo record. The great thing about when the band broke up was, we did it with no animosity. Nobody wanted to sue anybody; everybody just kind of drifted apart. We had toured for six years, and after Billion Dollar Babies, everybody just kind of went, ‘Wow… I’m exhausted. Let’s get paid and go buy some houses and do, you know, whatever.' But the three of us – me, Shep and Bob Ezrin – we had an idea for something that was going to be bigger than Billion Dollar Babies.

“At that point, that’s when I think I lost the other guys. To me, when you’re coming off a number one album like Billion Dollar Babies, that’s not the time you want to back off. You have to hit people with something even better. When nobody wanted to go on that ride, I just went, ‘OK.’ Bob said, ‘I’m in,’ Shep said, ‘I’m in.’

“We went out and shopped around; Bob and put a band together that was the best of the best, and we sat down and wrote this album. Again, it doesn’t matter if you think you have 10 number one hits, because when you go out solo you’re really taking a chance. It’s never a sure thing; it’s always a gamble. Shep put all of his money into the production. I did, too, as did Bob. We rolled the dice and went, ‘Boy, this really better work.’

“As for the band breakup… I grew up with those guys. I went to school with them, I ran track with them, I went to art class with them – this was all before The Beatles. We went through high school together, we went through college together, we went through the draft board together, we lived in LA together, we starved together, and then we made it together. We really did well for quite a while.

“So going out on my own after being literally attached at the hip to these other four guys, it was definitely weird and a little scary. But I had so much faith in Bob and Shep, and I knew what I had. I knew I had great songs, and I knew I had an idea that everybody was gonna love – being in Alice Cooper’s nightmare. It was the perfect time for that, actually.

“We even got Vincent Price on the album. We were saying, ‘Who’s going to be the curator at the spider musician?’ We started ticking off names – Christopher Lee, this guy, that guy… Bob Ezrin went, ‘Well, Vincent Price would be the ultimate.’ I thought there was no way that could happen, but we gave him a call and he said, ‘When do you want me over there?’ I was like a little kid – Vincent Price! He came over, did the vocals, and he even did it on stage with us. He did the video, too. It’s like he was in the band for about a month.”

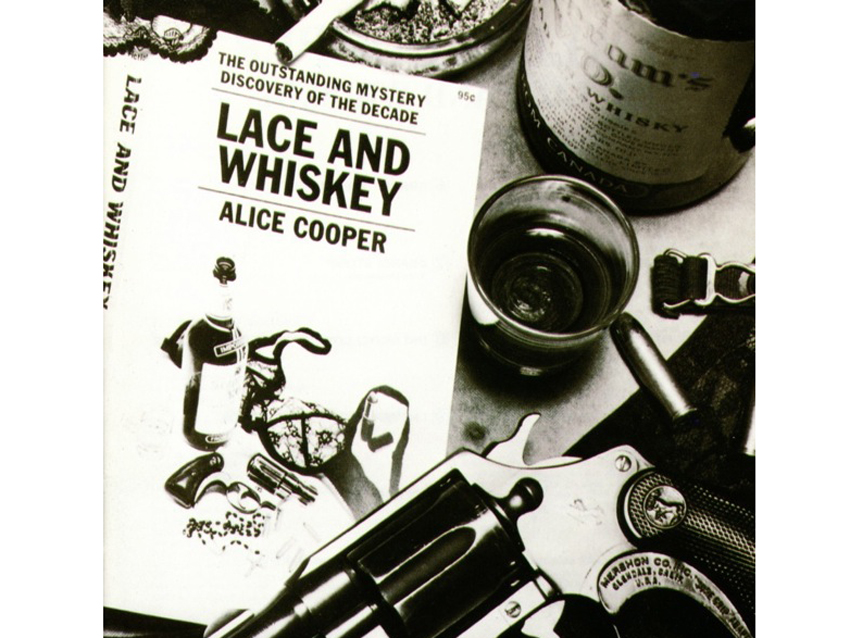

Lace And Whiskey (1977)

“My wife, Sheryl, and I were very good friends with Peter Sellers. He used to call me Inspector Maurice Escargot, and he called Sheryl Nicole Escargot. We stayed friends until the time he died. When he was in the hospital, I would send him telegrams: ‘Don’t worry, I’m on the case – Escargot.’

“Since he gave me that name, I thought about doing a film noir kind of thing, Lace And Whiskey, and I would make Escargot a ‘40s detective character. Even though none of the songs pertained to that, we still gave it that flavor.

“At this time, we were starting to see the problems with alcohol. We had just seen a bunch of successes in a row without stopping, and once we got going it just didn’t stop. That was my fault and Shep’s fault for not saying, ‘We need to take a year off.’ We were afraid to take a year off, because here comes Kiss, here comes Aerosmith. All of these really good bands were coming up, and I didn’t want to give up that throne. So we just kept going till we ran out of gas.

“There were good songs on the album, but it wasn’t always a coherent record. I think, at this point, people were looking to Alice to be the Stephen King of music, where every song was connected to a story. The record had a great look to it, but we didn’t put it together into a lyrical whole.

“You And Me was a big hit. It’s funny, because the easiest thing for Dick Wagner and I to write were ballads. We wrote four in a row that were Top 40 hits: You And Me, Only Women Bleed, I Never Cry and How You Gonna See Me Now. If we wanted to write something that we really knew how to do, it was those heartbreaking ballads. Hard rock was harder to write, because there was so much of it around. You really had to work at being original.

“There was no shame in having ballads. Back then, the power ballad was your golden ticket. Kiss had it with Beth, we had ours – every hard rock band had that one song the girls cried over.”

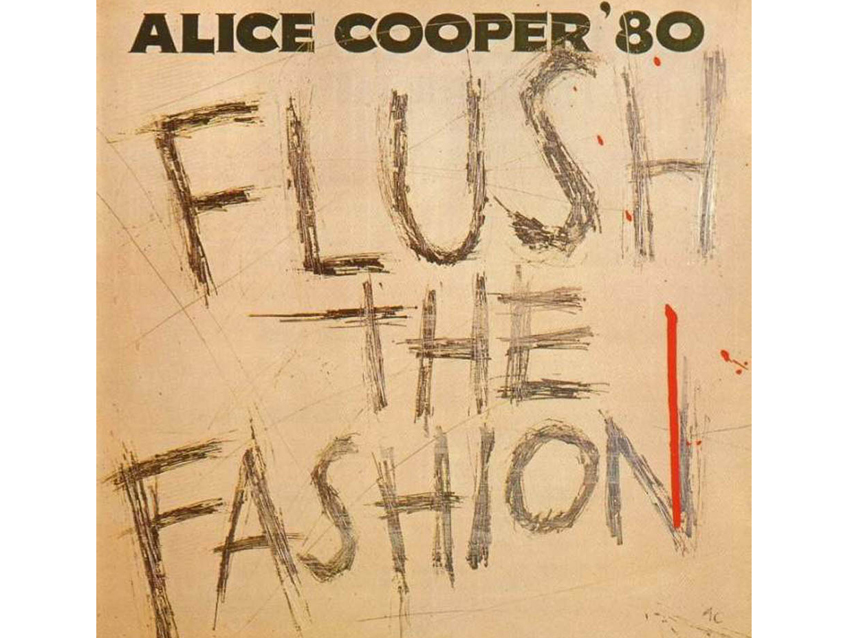

Flush The Fashion (1980)

“It was one of those things where you don’t worry about chasing the charts, but you also don’t ignore what’s going on with radio. We weren’t going to give up Alice Cooper or hard rock, but it was like, ‘We’ve heard My Sharona, we’ve heard The Cars – what would happen if we got the producer who does that type of thing?’ And that was Roy Thomas Baker.

“Roy Thomas is a very hands-on producer, especially with songwriting, which I really like. I always think that a producer should be a musician who is also an arranger. You don’t just bring a song to him and expect him to produce it; you want him to be part of the writing of the song. Roy Thomas came in and asked me what I was looking for, and I said, ‘I want Alice Cooper, but I want it in the style of what’s being played on the radio now.’

“I didn’t want to give up Alice’s edge, but I saw that it could be twisted. We did the song Clones, which was a Top 10 hit. It was different for me, but I think the twist was that it was Alice doing that song. I went through the National Enquirer, and I said, ‘Every headline is going to be the name of a song.’ Aspirin Damage, Grim Facts – stuff like that. It was very artsy, songs like Leather Boots. I told Roy Thomas that I wanted to cover Talk Talk by the Music Machine – he slowed it down.

“I don’t mind saying this: If they were ever going to do the story of Nero, probably the most decadent of all the emperors, they would have to use Roy Thomas Baker. He would call me up and say, ‘Alice, darling, I’ll be a little late today. I seem to be handcuffed to my bed.’ I would go, ‘What?’ And he’d say, ‘Yes, two little girls I picked up at the Whiskey last night; I woke up, handcuffed to my bed, and they ran off with my wallet and my Rolls-Royce.’ I’d laugh, like, ‘That’s funny.’ And he’d go, ‘No, no, I’m quite serious.’ He was, too.

“This was a daily routine with him. I went, ‘Wow! They call Alice Cooper decadent. I’m nothing compared to Roy Thomas Baker!’ But you know, he’s an amazing character, and he’s so good in the studio. He would never say anything was good or great. He did this with Queen, he did this with The Cars. It was always, ‘That’ll do.’”

Constrictor (1986)

“When I went into the hospital, I’d had four big hits the were ballads. People thought that I’d gone totally crooner. What really happened was that the only thing they were playing on the radio was disco. If you were a rock band like Kiss or Aerosmith, you were up against that. That’s what led to the birth of the power ballad, and I had four of them. I was still rock ‘n’ roll, and the rest of my albums were rock. But radio would only play the ballads.

“When we did Constrictor, I had found Kayne Roberts, who is probably the funniest human being I’d ever worked with. I always said that he had Stallone’s body and Jerry Lewis’ brain. I never laughed so hard as when I worked with Kayne. But we both had something in common: We loved the slick new ‘80s metal. The songwriting was strong, the melodies were brilliant. Kayne could play anything that Eddie Van Halen or Steve Vai could play, but he was so imposing with his body and his stage look, people forgot to listen to him. But he was a great writer, a great player and a great singer.

“I wanted to come back hard and slick on this record. I think there was even a sticker on it that said, ‘Contains No Ballads.’ The important thing about it is, when I did my re-emergence as Alice Cooper, I realized that the Alice who was an alcoholic was an outcast victim; he was always the whipping boy. I said, ‘This Alice is going to be the ultimate villain.’

"This Alice had broken out of his cocoon, and now he’s this really dangerous butterfly. I wanted him to wear all black leather, and I wanted his posture to be straight up. And I wanted him to have a kind of Alan Rickman arrogance. It was going to be fun to play that character. Doing Constrictor and Raise Your Fist And Yell, the idea was to really establish myself as ‘hard, hard Alice’ – but slick.”

Trash (1989)

“It was turning into another butterfly. You know, when you’re out on an ocean, you roll with the waves. Here comes these waves of bands from the Sunset Strip and New Jersey that are very slick, write really good songs and have great stage shows. I felt right at home. All of these bands reminded me of us.

“As it turned out, they would cite Alice Cooper as one of their influences. So I was a bit of a patron saint to all of the bands. I would listen to their records and say, ‘Geez, this is really good. What’s the common denominator?’ And the common denominator was Desmond Child. From Aerosmith to Bon Jovi, it kept coming up with that name. I said to Shep, ‘We gotta get in touch with this Desmond Child guy.’

“He was living in a commune in Charlotte, North Carolina. I don’t think he had any idea how big his songs were. Shep and I pulled him out of the commune and said, ‘Not only are we going to write with you, but we also want you to produce the album.’ All of this was new to him, but he did an amazing job.

“I worked with Aerosmith and wrote with Bon Jovi. It was really great because there was a lot of respect going on both ways. We came up with a lot of amazing songs. Next to Bob Ezrin, Desmond was the premier song doctor. The very first thing we wrote was Poison, which was the biggest international hit I’ve had - it was bigger than School’s Out.”

The Last Temptation (1994)

“Almost all of my records are conceptual, but this one is more so. I wanted to do something that was along the lines of Something Wicked This Way Comes. The idea was great: The circus comes to town, and for a certain 16-year-old kid, the circus offers him everything in the world.

“Of course, the metaphor was almost Jesus being tempted by Satan in the wilderness. I wanted the Showman to be Alice Cooper. When they put the comic book together, I worked with Neil Gaiman on the idea that everything this kid sees on the outside is really sparkling and enticing – everything a 16-year-old kid would want. But in the comic book, when you see it from the back, it’s all rotting away. The face value of it only went so deep, and behind it was something really evil. It was amazing how they captured that.

“The point of the album was, a 16-year-old kid doesn’t have to buy into everything the world is selling. You can say no. The shocker at the end, when the kid finally says no, is something that the Showman can’t understand it at all, and he has to leave. The kid saying no is the holy water and the cross to the Showman – it drives him away.

“It was a great conceptual album, and they did three fantastic comic books for it.”

Along Comes A Spider (2008)

“This was another story. I liked the idea of writing about a serial killer, starting with the CSI officer saying, ‘We found this diary today. We think we know what he’s doing, and it all makes sense, except for one thing’ – and then the album starts.

“You hear the point of view of the serial killer talking. In his trail, he leaves eight victims wrapped in silk, all of them missing one leg. He says, ‘How obvious is that? I’m creating a spider.’ At the end, you hear him in the insane asylum talking to his pet spider. He’s going, ‘How clever it all was. They found my diary today. Eight legs, wrapped in silk. But we’ve been in here 28 years – I couldn’t have done any of this.’

“So you’re left thinking that all of this happened in the diary, or there’s another killer. I leave the audience with that. Now, when I started writing Welcome 2 My Nightmare, I had already written the ending to this story called The Night Shift... ”

Welcome 2 My Nightmare (2011)

“I brought this to Bob Ezrin, and when we started writing it, I said, ‘You know, it’s the 35th anniversary of Nightmare. Instead of doing part two, let’s just give Alice a new nightmare.’ That was the idea: What would drive Alice crazy 35 years later? I never had more fun writing an album as I did this one. Bob and I were hitting on all cylinders.

“Of course, hip-hop would irritate Alice, so Disco Bloodbath Boogie Fever was Bob and me at our funniest, I think. We just went through it: ‘What would this nightmare be?’ Technology would drive Alice nuts, ‘cause he’s an old-school villain. Every single song was a part of the nightmare. I think that it came out with a lot of humor, and it was one of the best-sounding albums we’d ever done.

“Bob and I are joined at the hip. The unholy trinity is Bob, Shep and me. Even when I was working with other producers – Roy Thomas Baker, David Foster, you name them – if I had 10 songs, I would send them to Bob. ‘Bob, what do I have here?’ And he’d give me notes on how to make them better. He’d say, ‘These six are songs. These four are pieces of songs. Where’s the chorus? Why is it going here? I don’t get it.' I would always use him as my sounding board, no matter whom I was working with. He was my George Martin.

“Like always, he’d say, ‘It’s too complicated. Dumb it down.’ Or he’d go the other way and say, ‘Not complicated enough. You’re not giving me enough information.’ So Bob has always been there with me, but of course, it was fantastic to really work on this album with him. I’m so happy with it.”

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.

Zak Starkey is back in The Who. “I take responsibility for some of the confusion… Zak made a few mistakes and he has apologised”, says Pete Townshend

“I oversaw every element - not just the music and the lyrics and the melodies and the production, but also the merch and the fan clubs and everything”: Mike Portnoy talks about his years away from Dream Theater

Zak Starkey is back in The Who. “I take responsibility for some of the confusion… Zak made a few mistakes and he has apologised”, says Pete Townshend

“I oversaw every element - not just the music and the lyrics and the melodies and the production, but also the merch and the fan clubs and everything”: Mike Portnoy talks about his years away from Dream Theater