Keith Emerson talks ELP's Brain Salad Surgery track-by-track

When Emerson, Lake & Palmer released their fifth album, Brain Salad Surgery, on November 19, 1973, the band's extravagantly audacious blend of outer-limits progressive rock, fantastical re-imaginings of classics and lush, pastoral pop balladry reached both a creative and commercial peak. ELP's previous efforts reached sizable but somewhat disparate audiences – art rockers flocked to Tarkus and Trilogy while curious classical adventure seekers embraced Pictures At An Exhibition – but with Brain Salad Surgery, the trio put the mainstream directly in their crosshairs without sacrificing their prodigious instrumental chops.

"We were still ascending when we made Brain Salad Surgery," Keith Emerson says. "We were enjoying a sensational amount of success, and I suppose we felt as if we could do anything – and we certainly tried. Musically, lyrically and visually, we really went for it."

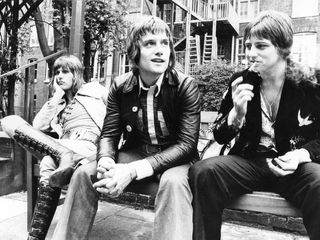

The album would be the inaugural release by the band's newly formed Manticore label and would differ from the extensively overdubbed Trilogy in that the group plotted out the music as a largely live creation. At the start of 1973, Emerson, Greg Lake and Carl Palmer purchased an abandoned cinema in Fulham, London, and converted it into a rehearsal and production facility, using an upstairs foyer to assemble and run through new compositions.

“That was the general idea, to play the album live," Emerson recalls. "I pretty much had the whole concept in mind. We had taken a bit of a break to be with our families, so that gave me a fair enough time to put down enough hand-written ideas for the Karn Evil 9. I then approached Greg and Carl with a sheaf of manuscript papers, and we set about rehearsing, going over the material and being sort of repetitive about it."

Once the epic Karn Evil 9 was worked out – the 30-minute sci-fi tale of man vs machine would spill over from side one and encompass the whole of side two – ELP loosened up with the deliciously lighthearted honky-tonk saloon spoof Benny The Bouncer. "We liked to get the serious stuff out of the way and then do something fun," Emerson says. "We had done Are You Ready Eddy? and The Sheriff before. It was always a nice little breather to soften the mood, both in the studio and on record."

To complete the lyrics to both Karn Evil 9 and Benny The Bouncer, Lake recruited his old pal and former King Crimson bandmate Peter Sinfield. "Greg had always been a prolific songwriter and lyricist," Emerson notes, "but at this particular time he needed the influence of somebody he had confidence in. Pete brought a lot of fantastic ideas and lines to the songs.”

Recording took place between June and September of 1973 at London's Advision and Olympic Studios, with Lake, as he had done on the group's previous albums, serving as producer. "It was a pretty straightforward time in the studio," Emerson says, "even with some of the new pieces of equipment we were using, like the Moog Apollo. Because we were so rehearsed, there wasn't a lot of mucking about. We didn’t have Pro Tools and all the things that exist now. If a person made a mistake, you didn’t say, ‘Oh, we’ll fix that later.’ We really had to get it right as we played together."

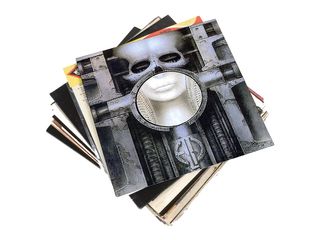

Originally, the album was to be called Whip Some Skull On Ya – a slang expression for fellatio. The eventual title of Brain Salad Surgery, nicked from a lyric in Dr. John's hit Right Place, Wrong Time, dismayed artist H.R. Giger, who had been commissioned by Emerson to create the jarring and groundbreaking cover art. When Emerson explained that Brain Salad Surgery carried the same connotation as Whip Some Skull On Ya, Giger was greatly relieved.

By the decade's end, Giger's work would become famous from the film Alien, but in 1973 he was still regarded as something of an underground artist. Emerson had been made aware of the Swiss surrealist by Manticore's Peter Zumsteg, who drove the keyboardist to meet with Giger at his Zurich studio. "The second I walked in, I was absolutely amazed," Emerson says. "The artwork represented the music we were working on as fully as I could have imagined. The next day, I told Greg and Carl, ‘You’ve got to some with me to see what this guy is doing.’ I think they were kind of reluctant at the beginning, but once they saw his stuff, they were incredibly intrigued. I’m so pleased with where we went for the cover. I think it’s one of the best pieces of album art I’ve ever seen, to be honest."

The across-the-board success of Brain Salad Surgery – helped in large part by the nearly constant spins of Karn Evil 9's First Impression, Part 2 on FM radio – cemented Emerson, Lake & Palmer's worldwide popularity, and the group capitalized on their fame with a stage show so grandiose (over 36 tons of gear, complete with levitating, spinning keyboards and the world's first discrete quadrophonic PA system) that the only band who could top them was... Emerson, Lake & Palmer! And, sure enough, in 1977 they did just that, bringing a 70-piece orchestra on the road for the budget-busting Works tour.

On April 7, 2014, Razor & Tie will issue a three-disc 40th Anniversary Deluxe Edition of Brain Salad Surgery, which includes the remastered original album, an "alternate album" that features previously unreleased material and a DVD-A of new 5.1 mixes of the original album. You can pre-order the Deluxe Edition and various bundles of the set at elp.merchnow.com.

"It's always hard to pinpoint why a particular album hits the mark and lives on and on," Emerson muses. "Out of all our other records, this was our biggest, and even today, it’s the one that most everybody knows. It really touched a nerve with a lot of people."

On the following pages, Emerson recounts the writing and recording of Brain Salad Surgery track-by-track.

Jerusalem

“We wanted the opening to be startling, and this number certainly does take you by surprise. What was surprising to me was when the song gave the media the idea that we’d become born-again Christians. I’ve got no objection to born-again Christians, but that certainly wasn’t the case, nor was it the intention behind the song.

“To me, the lyrics are a little bit like Procol Harum’s A Whiter Shade Of Pale. I didn’t really connect any kind of religious element to it at all. I just thought it was a damn good song. Every kid at school knew the Jerusalem – it’s so majestic.

“I remember, back in the ‘60s, I worked on an arrangement of it with The Nice. It didn’t come across somehow, but with ELP it came together quite nicely. I think we knew how to embrace the sense of drama in the music and organize it properly, and I think that Greg felt comfortably singing it, which helped, as you can imagine.

“I used the Moog Apollo on it. This was when the Moog company decided to go polyphonic. I would help Bob Moog out on his different inventions. The Apollo sounded incredible. It wasn’t an easy song for Carl to lay down the drums on. It was a little bit like when he had to put on the drum parts for Lucky Man, from the first album. Greg had already recorded his guitar work, and of course, there was no click track to work from. These are the challenges with recording.”

Tocatta

“I’d first heard Alberto Ginastera’s Tocatta from his Piano Concerto No. 1 in 1969. It just completely blew me away. When Carl and I got together, he was very keen on doing music by Bartok and some other composers because he knew that I liked the classics. When this piece came to my attention, I started to play it and Carl said, ‘What the fuck is that?’ He was excited and wanted to try it. I don’t think Greg was too into it at first.

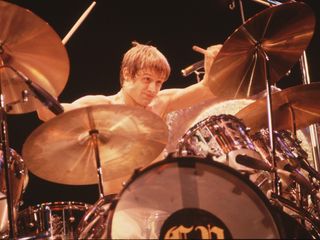

““I used a Minimoog on this and, of course, a Hammond organ – they were lined up in locality to each other. Carl had quite an arsenal of equipment for making his drum sounds. We wanted to do something quite extraordinary, and I think he really pushed himself to the limit on this track. The music lent itself to experimentation – it wasn’t the kind of thing you could sing along to. We all got caught up in that feeling of adventure: If somebody did something exciting, somebody else extended it.

“After we’d spent about two weeks recording, it came to management’s attention that we should get permission from the publishers, which, in this case, was Boosey and Hawkes. I approached them and they said, ‘Nope. Sorry. We don’t think Maestro Ginastera will want to give approval to this.’

“I wasn’t going to take no for answer. I got his Alberto’s number and spoke to his wife. The next day, I was on a plane to Geneva with Stewart Young, our manager, and we found ourselves in Alberto’s apartment. He served us a brilliant meal, and we talked about music and synthesizers – he had a rough knowledge of synths and was interested in. At the end of the lunch, he wanted to listen to my adaptation of Tocatta.

“I had the tape with me, so we went into his studio. I think he had a Revox reel to reel tape recorder. I played it for him, and when it was over he had a strange look on his face. He seemed to be extremely astounded, and he said something like ‘That is terrible.’ I interpreted that as literally that – terrible. I thought, ‘Well, that’s it. We obviously can’t use that one.’ But then I learned that in French ‘terrible’ means the same as ‘formidable’ or ‘unbelievable.’ He was, in fact, overwhelmed by the recording, so all was fine.”

Still... You Turn Me On

“Greg did the writing on this song. Like with Lucky Man, it was introduced right at the very end of the recording. We had kind of developed a trend where I would work on the epics like Trilogy and Tarkus, and Greg would come up with the ‘Greg Lake ballad,’ which were quite important for the appeal of the records.

“The way he would introduce the songs to us was funny – and fairly typical: Greg would come into the studio and say, ‘I’ve been thinking…’ And then he’d put his guitar on, strum away, and Carl and I would be like, ‘Hey, that’s all right. That sounds good.’ You know, I always love to hear other people’s compositions. I find it rather challenging to try to find what it is I need to do to bring something out of what somebody else has written. Like on this song, I played a harpsichord. It's good fun, that challenge – and I always enjoyed doing that with Greg's music."

Benny The Bouncer

“This one came about rather like Are You Ready Eddy? From Tarkus, only with a bit more structure. We had gotten the major concept and the big tunes out of the way, and we became fun. We decided to loosen up, we started jamming, and Benny started happening.

“Greg sounds great on this, that gruff accent and the bellowing voice. [Sings] ‘Benny was the bouncer at the palais de dance!’ Brilliant. He sounds like an authentic West End Bouncer, if you ask me.

“Carl plays the brushes, and that totally works with the tune and the honky-tonk piano sound that I got. I used an upright piano that I detuned so that it was a little 'off' and old-sounding. It was a good piano, but it got shipped around a lot – I don’t know what happened to it.

“It’s a sort of shock value, this song, a nice release. You don’t want to telegraph each thing as you move along your way. Benny The Bouncer is lighthearted and it moves into the more serous piece…”

Karn Evil 9: 1st Impression, Pt. 1

“I thought the piece might turn out to have more of a fugal development. It’s not really a fugue, though; it’s more of a counterpoint – you get one theme ending and another one starts underneath it. I guess the closest you get to it is a canon.

“It evolved pretty much like all of the other ELP concept albums: me at home, writing on manuscript paper, doing scribblings and things like that. My main concern was that I was coming up with something memorable and that it could be played by an orchestra one day. The whole piece was worked out instrumentally; we had no idea where we were going lyrically; we didn't even what to call it. I didn’t think up with the title; it actually came from Pete Sinfield. He was doing a play on the word ‘carnival.’

“Once I had it all written down instrumentally, I went to the rehearsal studio and ran it through with Greg and Carl, how the bass should go, how the drums should go. Of course, they came up with their own ideas, and I’d say, ‘Yeah, that’s cool. We can use that – I’ll change what I’m doing then.’ For a month we went over and over it, playing it all day. Finally, we felt good enough to bring it to the recording studio. You can’t just bash out a piece like this; you’ve got to really know what you’re doing.

“There’s the main hook part, the sort of anthem riff – at some point it developed into a bohemian or Jamaican feel. I think it gave Carl a lot to work with so he could add a lot of syncopations on the drums.”

“There is a bit of Beatles in the lyrics – ‘roll up’ and the idea of a show, like with Sgt. Pepper. I was a bit nervous about that, but I thought we were going something very different from what they had done. The music along with H.R. Giger’s artwork, it was definitely more bizarre.”

Karn Evil 9: 1st Impression, Pt. 2

“Pete was in the studio writing a lot of lyrics: ‘Here behind the glass is a real blade of grass. Come inside, come inside.’ It had a real commercial element to it, and the riffs were very strong.

“This particular part of Karn Evil 9 got played on the FM radio a lot. I think the fact that it started off side two didn’t hurt. You had to flip over the vinyl, and this was the first thing you heard – [sings] ‘Welcome back my friends to the show that never ends.’

“It’s a tight, well-constructed piece of music. The solos were plotted out well – the keyboard solo into the guitar solo into a bit of a drum solo. The tempo might slow down just a bit at one point. Carl’s a brilliant drummer, of course, but all drummers can vary slightly in time. That’s just the nature of a human being playing an instrument. Again, no click tracks.”

Karn Evil 9: 2nd Impression

“I was dabbling at the piano, and before you knew it, I had something pretty nice. It’s a jazz piece, really, partially inspired by Chick Corea, perhaps.

“There weren’t many electronic keyboards around at the time, so I used a regular piano. I liked to do crazy things like sticking pins in the keys, and knives occasionally. I didn’t do anything like that on this track.

“I had a Minimoog on top of the piano, and that’s what I used for the marimbas. There’s a bit of steel drums, too – again, the Minimoog. I found it to be a very versatile piece of gear. I played everything at the same time; there were no overdubs. Luckily, I had three hands at my disposal." [Laughs]

Karn Evil 9: 3rd Impression

“It’s very heraldic. As with most of my compositions, I like to have some bravado, especially as we near the finish. Tchaikovsky’s Pathétique ends on a very somber note. The third movement is what everybody applauds, but you get to the fourth movement and everybody’s in tears. You can’t really clap for that.

“I didn’t want any of ELP’s music to send people away crying, so I went for something more anthemic and rousing. It’s not really cheery per se; there’s a bit of foreboding, particularly the way it all ends. There’s a lot of light and shade in this cut, the soft and the loud.

“There are three oscillators in the Moog synthesizer, and I detuned them slightly to give them a particular ring, very much like what I did on pianos. That worked really well on the synth horn parts. Oh, and you hear the voiceover l did, like a computer voice – I did that as a joke.

At the very end, that’s the Moog going crazy – it’s sped up to sound like an out-of-control computer. I programmed each note one at a time, twenty-four notes in the pattern. They sort of ping-pong off one another as it goes faster and faster and sputters out. It took a while to program, as you can imagine. Live, we had a set design and a bunch of lights that responded to the notes and then kind of blew up. It was pretty cool.”

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.

“I did a demo. I had Sheila E playing on it and Michael sang on it. I played it for Quincy and he said, ‘No.’”: Greg Phillinganes on the Michael Jackson song arrangement that Quincy Jones rejected because it wasn't "sexy" enough

“I was going to buy a Minimoog because Keith Emerson had one. I was in the store and I was trying it out and I hear a voice behind me say ‘you don’t want that’”: Why Foreigner’s Al Greenwood said no to the Minimoog and bought a little-known synth instead

“I did a demo. I had Sheila E playing on it and Michael sang on it. I played it for Quincy and he said, ‘No.’”: Greg Phillinganes on the Michael Jackson song arrangement that Quincy Jones rejected because it wasn't "sexy" enough

“I was going to buy a Minimoog because Keith Emerson had one. I was in the store and I was trying it out and I hear a voice behind me say ‘you don’t want that’”: Why Foreigner’s Al Greenwood said no to the Minimoog and bought a little-known synth instead

Most Popular