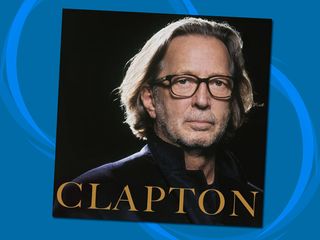

Clapton review: intro

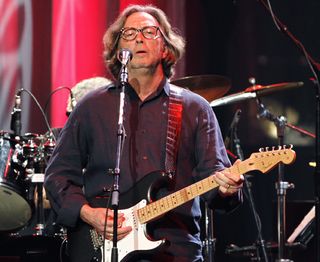

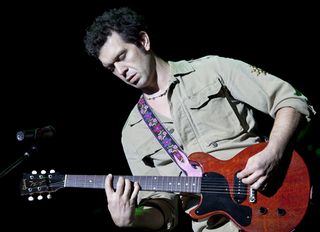

His brief, 2005 reunion with Cream notwithstanding, it would seem foolhardy, if not downright disrespectful, to demand that Eric Clapton revisit his past by rehashing some misguided attempt at Wheels Of Fire or Disraeli Gears. Over a distinguished, nearly 50-year career, the man has earned his right to play whatever music he likes, however he pleases.

But on Clapton, his 19th solo album, the guitarist who's been called everything from Slowhand to God does revisit his musical past, some of it blues nuggets he cut his teeth on, a handful of numbers from his friend and frequent collaborator JJ Cale, and the bulk of it (the most fascinating portion of all), music that was passed down from his grandparents.

"I never liked young kids' music," Clapton has said, explaining the origins for this album. "I like old people’s music. When I look for what I’m going to listen to, I go backwards. Most people are trying to figure out, 'How do I get in the fast lane, going that way?' I’m going in the other direction - I want to find the oldest thing to do."

Working with his trusted confidant, guitarist and producer Doyle Bramhall II, Clapton assembled a glittering array of talent to back him up on this self-titled release, including drummer Jim Keltner, bassist Willie Weeks and keyboardist Walt Richmond - the sessions later added guests stars such as Cale, Wynton Marsalis, Sheryl Crow, Allen Toussaint and Derek Trucks. Not too shabby.

As an archeological musical study, the record sees Clapton mining still-fertile ground, addressing songs by such noted composers as Irving Berlin, Fats Waller, Johnny Mercer and Hoagy Carmichael. But the surprising thing about Clapton, the album, is the remarkable manner in which the guitarist, singer and songwriter makes each cut his own. This is no mere ’covers album’ (see Rod Stewart for that). This is Clapton courageously walking down the hallways of reinvention and discovery. For a man of 65, that’s got to be exciting.

And for us, the audience, it’s a rare and unexpected gift. Clapton will be released 27 September in the UK and the following day in North America. But why wait? Let’s check out Clapton track-by-track right now...

Travelin' Alone

This swampy reading of Lil’ Son Jackson’s blues chestnut starts so abruptly, you’ll feel as though you opened a door and walked in on a band in mid-jam. But within seconds, you’re spellbound, put into a trance.

Over a hypnotic beat that never loses its momentum, Clapton and Doyle Bramhall II lock guitar horns, both players plucking spare chords and snaky little lead lines with the right amount of dirt dialed up on their amps. Clapton’s singing is ghostly - it’s as if he’s a troubled yet wisened spirit in the dark - and it's punctuated by Walt Richmond’s Hammond organ swells, which seem to pop up with the randomness of a groundhog in a field.

As a mood piece, Travelin’ Alone is something of a revelation in that it manages to be unnerving, totally captivating and, ultimately, a balm to heal one’s soul.

Rocking Chair

Should you ever stroll into a lounge and find Walt Richmond on piano, Abe Laboriel Jr on drums and Willie Weeks on bass, sit yourself down and order a martini, because you’re definitely in the right place. And if, by some miracle, a fellow who goes by the nickname of Slowhand decides to sit in, then it’s official: there’s no other spot on earth one needs to be.

On this Hoagy Carmichael standard from 1929, covered by artists such as Louis Armstrong, The Mills Brothers and Lonnie Johnson, to name a few, Clapton wraps his relaxed, smooth tenor voice - increasingly a thing of affecting simplicity - around the gliding grace of Laboriel’s brushes the way Doris Day used to slip into a mink. He luxuriates in each phrase, and so why shouldn't we?

Derek Trucks contributes exquisite slide guitar throughout, and his brief, tasteful solo spot is guaranteed to impress. Young as he may be, he’s no mere whippersnapper. He's got the heart of someone who’s lived a long and rich musical life.

River Runs Deep

JJ Cale songs are objects of beauty to be admired, but not from a distance - and Eric Clapton, who has, since the early '70s, made definitive recordings of several Cale compositions (After Midnight, Cocaine, for starters) knows how to get inside them like nobody’s business.

River Runs Deep is a slow blues burner from 1971, and with Clapton and Cale trading both vocals and guitar licks, backed by the London Session Orchestra, we have yet another superlative rendition.

Clapton turns in an arresting mid-song guitar solo, starting with biting top string bends and ending with groaning bass notes. But the real trip is the end run, which features leisurely paced and carefully phrased backwards guitar lines. This is a track to lose yourself in. Careful, though: you might never want to come back.

Judgement Day

Doo-wop vocals kick off this amblin’ bit of shufflin’ blues, written by the American harp player Snooky Pryor, who is credited with pioneering the now-common method of cupping a small microphone in his hands while playing the harmonica.

Clapton sings in a playful manner, like he’s kickin’ back on his porch on a hot Sunday afternoon. He takes his good ol’ sweet time, too (the word 'long' becomes 'lawwwng' in his elocution), clearly waiting for Kim Wilson to shine on the harp, and oh, how he does.

In Wilson’s hands, a harmonica becomes the equivalent of a Stradivarius, and the emotive quality he produces from the instrument has life-giving force.

How Deep Is The Ocean

Amid Willie Weeks’ fluid upright bass, Jim Keltner’s expressive brush strokes and the lush strings of the London Session Orchestra, Clapton turns in a husky, sensual vocal, so warm that it could melt the frostiest of hearts.

Irving Berlin, the Dean of American Songwriters, might not have envisioned an electric guitar solo when he penned this infectious ballad in 1932, but Clapton’s playing, not to mention the rich, bell-like tone he coaxes from his six string, drips with lyricism.

Towards the end, the legendary Wynton Marsalis graces the song with a trumpet solo that is a marvel of phrasing and tonal invention. When the orchestra rises to meet both guitarist and trumpeteer, you’ll be swept off your feet as you trip the light fantastic.

My Very Good Friend The Milkman

Written by Harold Spina and Johnny Burke and popularized by Fats Waller, that master of stride piano who would later become a musical institution unto himself, this charming jazz number is in good hands with EC, whose sly, confident performance is one of the album’s devilish highlights.

Walter Richmond and Allen Toussaint share the piano spotlight, with a most impressed Clapton introducing each player by name, but instrumentally, the song belongs to Wynton Marsalis, whose sassy lines throughout almost serve as a vocal accompaniment.

A frothy look at look at love, romance, courtship and marriage. But oh, just wait till you hear Slowhand’s ad lib at the end - hysterical!

Can't Hold Out Much Longer

Marion Walter Jacobs, better known as Little Walter, harp player extraordinaire and an important figure in the history of Chicago blues, gets his due here from Clapton and company.

The tempo oozes sex and romantic yearning, and Clapton sings each phrase like a man who’s known loneliness his whole life. Midway through, Kim Wilson peels off a greasy harp run, which is then bested by Slowhand himself, whose searing guitar solo is filled with exhilarating twists and turns. Sweet, velvety and high-pitched, with just a trace of bite... you know what it is: it's Clapton's famous 'woman tone.'

Only musicians of the highest order know not to overplay their hand. Clapton's been a monster of taste and sensibility for years, and on this authentic blues howler, he demonstrates why they used to call him... Come to think of it, they still call him that.

That's No Way To Get Along

Fans of The Rolling Stones will no doubt recognize this syncopated blues shuffle as Prodigal Son from the album Beggars Banquet. Fact is, it began its life as That's No Way To Get Along and was written by American blues guitarist and singer Robert Wilkins. Wilkins later became an ordained minister and changed the title and some of the 'unholy' lyrics to the song.

Clapton eschews the bare-bones acoustic treatment that the Stones employed and returns it to its secular roots. His large band, complete with horns and the stellar Walt Richmond tickling the ivories, gives the number a laid-back yet righteous groove, propelled by the inimitable talents of drummer Jim Keltner. When you look up 'feel' or the expression 'in the pocket,' this man's name surely must appear.

Clapton and JJ Cale trade off on vocals and guitar duties, but both men are more than happy to step aside and let Doyle Bramhall II take not one but two solos. The man knows how to build tension and dynamics. For the most part, his touch is light, his fingers just teasing the strings with soulful bends; at the end, however, he lays it all out and kicks up some distorted screeches and squeals. Peaking too early doesn't get the job done.

Everything Will Be Alright

JJ Cale's 'Tulsa Sound,' a loose style incorporating blues, rockabilly, country and jazz, all comes together here, in which Clapton once again trades vocals with the songwriter to soulful, dramatic effect.

The big band of strings and horns never overwhelms, and Paul Carrack's Hammond B3 provides just the right amount of tension and release.

But this is a Clapton album, and the man steps out for a end solo that is nimble and smooth. Not a scorcher this one, just a nice and easy bass-note-heavy run that fits the song like a glove.

Diamonds Made From Rain

One of the few new compositions on Clapton, this torch-like pop ballad, written by Doyle Bramhall II, Justin Stanley and Nikka Costa, is the perfect vehicle for EC's emotive, maturing tenor. No wonderful he's picked it as the album's first single.

Sheryl Crow sings backup in the chorus, and her sweet, melodious voice blends effortlessly with that of her longtime friend and one-time lover, Clapton.

Amid a full orchestra, Walt Richmond's piano stands out - that is until Clapton turns up his guitar and lets loose with a heartfelt solo, one of his best in years; in fact, each note is packed with passion. Some guys don't feel at all; others are all about feel. Check out EC's playing here and you know what side of the street he stands on.

Listen: Eric Clapton - Diamonds Made From Rain

When Somebody Thinks You're Wonderful

This Tin Pan Alley standard from 1935, written by Harry Woods and Fats Waller, will be familiar to Clapton's concert audiences, as he's been performing it live for a number of years.

Picking a star turn here is a daunting task, as you've got the subtle yet swinging drumming of Herman Labeaux, the dancing pianos of Richmond and Toussaint and, once again, the unparalleled trumpet playing of Wynton Marsalis. At times it seems as if they're all soloing at will, yet there's a musical connection the players share that is no less than telepathic.

Three-quarters in, Clapton steps up to solo, and it's clear he's enjoying himself - his notes are both sweet and sour, light and shade. Somewhere, Fats Waller is smiling.

Hard Time Blues

St. Louis metal worker Lane Hardin penned this self-explanatory blues in 1935. Things were rough then, they're rough now, and Clapton's forlorn delivery makes it abundantly clear that this is no more homage - this is breaking news.

The instrumentation is sparse, as it should be, with EC playing both guitar and mandolin. But hats off to Doyle Bramhall II, whose slide solo is soaked in both trouble and moonshine. A fairly behind-the-scenes man of many talents for over a decade, watch for Bramhall to become a major player (in both senses of the word) quite soon.

Run Back To Your Side

Clapton and Doyle Bramhall II wrote this gruff blues rocker, and the two guitarists are joined by slide wiz Derek Trucks, who injects some genuine Allman Brothers spirit into the proceedings.

This recording has everything fans of early to mid-'70s Slowhand could want: a swinging groove, a memorable, doubled (or is it tripled?) riff that forms the basis for the entire tune and a forceful vocal performance by Clapton, who, despite his years, manages to sound, at times, ageless.

Guitar goodness abounds, with all three players taking turns trading licks, weaving lines and working the kind of magic that will have you wondering if you've just advanced onto a copy of Layla And Other Assorted Love Songs.

Autumn Leaves

In 1947, Johnny Mercer adapted the French composition Les feuilles mortes (literally The Dead Leaves) and it became a pop standard, covered by artists raging from Edith Piaf to Nat King Cole to Cannonball Adderley to Bill Evans.

Over a gorgeous, hushed instrumental backing (Abe Laboriel Jr is an absolute genius with a pair of brushes), Clapton, always a superlative interpreter who reaches a new level here, sings in a tender baritone, his throat full of heartache and regret.

Best of of all, the man known as God plays not one but two guitar solos. At first he performs a breathtaking acoustic run in which he remains faithful to the haunting melody; his second solo is on an electric, and it's a towering achievement, with jazzy, bell-like tones giving way to notes that weep as they reach up to the heavens.

Liked this? Now check out 35 Stratocaster stars

Connect with MusicRadar: via Twitter, Facebook and YouTube

Get MusicRadar straight to your inbox: Sign up for the free weekly newsletter

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.

"It may have bothered him that people didn’t recognise his guitar virtuosity, which might be why the song devotes so much space to his shredding": A music professor breaks down the theory behind Prince's When Doves Cry

“It didn’t even represent what we were doing. Even the guitar solo has no business being in that song”: Gwen Stefani on the No Doubt song that “changed everything” after it became their biggest hit

"It may have bothered him that people didn’t recognise his guitar virtuosity, which might be why the song devotes so much space to his shredding": A music professor breaks down the theory behind Prince's When Doves Cry

“It didn’t even represent what we were doing. Even the guitar solo has no business being in that song”: Gwen Stefani on the No Doubt song that “changed everything” after it became their biggest hit

Most Popular