David Crosby talks songwriting, guitars and his new solo album, Croz

Twenty-one years separate the release of David Crosby's last solo album, Thousand Roads, and the appearance of his stunning new studio effort, Croz. But the two-time Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame inductee (for The Byrds and Crosby, Stills & Nash) insists that he doesn't spend his time minding the calendar when it comes to making music.

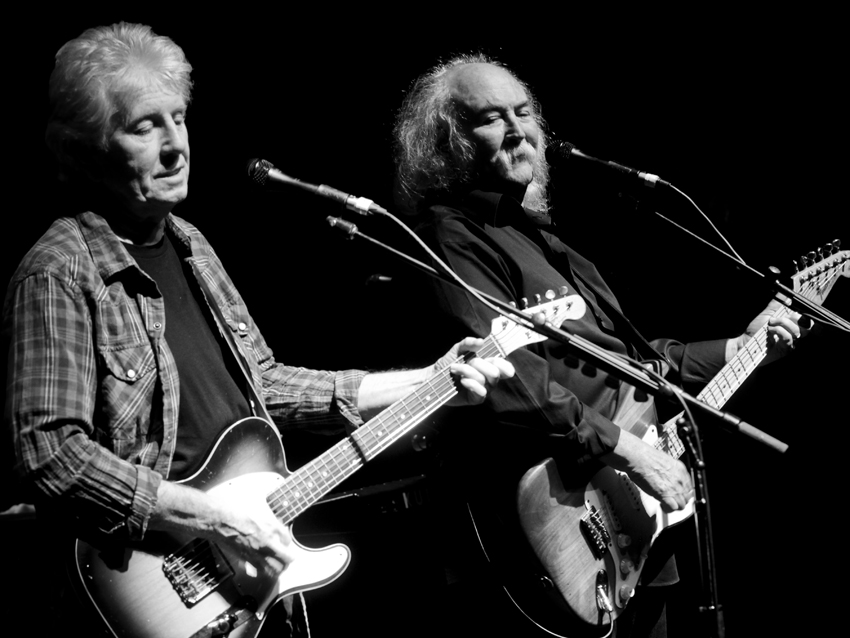

“People tell me that's a long time, and I guess it is," Crosby says, settling back into a comfy couch inside a hotel room in Lowntown Manhattan. "The fact is, I've been pretty busy. CSN has been touring, and a couple of years ago Graham and I made a double album. You know, I just don't make records to make records. I'm guided by the songs – you wait until they come."

Croz was recorded over a two-and-a-half year period at Jackson Browne's Groove Masters Studio in Santa Monica and Crosby's son James Raymond's home facility. Raymond, who co-produced the set and wore other hats during the process, hadn't met his father until 1995 (Crosby and an ex-girlfriend gave him up for adoption in 1962), but the two have formed a remarkably tight personal and professional bond, performing and recording together in a band called CPR, which also includes guitarist Jeff Pevar.

"James is has so much talent," Crosby says, his face radiating parental pride. "He can read music. He can write a chart for a whole orchestra – and has. On this record, he wrote, sang, played, arranged, engineered, mixed and produced. I couldn’t have made the album without him, and it was a total joy.” He chuckles, then adds, "We had a nice routine: I’d go to sleep on the couch bed in the studio. In the morning, James would wake me up, make me an omelet, and we’d go to work. A good omelet, too – gruyere cheese with shallots. He's a foodie, like me."

Croz features stirring contributions from Mark Knopfler and Wynton Marsalis, but the sonic focal point – set against sparse, understated instrumentation and arrangements – is Crosby's remarkably resonant voice. A deeply humanistic record – If She Called is an affecting observation of prostitutes the singer witnessed from afar one night, and Holding On To Nothing is an unflinching personal reflection that recalls the meditative brilliance of his classic Guinnevere – it's Crosby's collection of songs since his 1971 solo debut, If I Could Only Remember My Name.

"I was a little tickled when somebody put it together," Crosby says with an impish grin. "Croz... If I Could Only Remember My Name... Croz." He lets out a laugh. "I kinda like that."

It’s interesting: You started out when we were in a singles world. Then it moved to an album world, and now we’re back to a singles world.

“Actually, now I think we’re going into totally unchartered waters. We had thought about releasing one, two or three songs initially, and then one a month from there. I think that’s a doable scenario. The problem with that, and the reason why people haven’t done it, is that you only get one chance at the major meeting – you can’t keep going back to the well. That’s why we didn’t do it, but we were seriously thinking about trying.

“And, look, I have no problem breaking the rules. [Laughs] They were sort of made to be broken. But I do think that my new songs work together as a piece. If you listen to the whole record, everything makes sense, each song with the next.”

You’ve recorded some albums during very stressful times. Déjà Vu was made during a lot of turmoil.

“Oh, the worst. Absolutely.”

I get the feeling that you’re in a pretty happy place right now. [Crosby nods.] Is it hard to write when you’re content? Do you feel that conflict makes for great art?

“No. No, I wouldn’t say so. Conflict, in my opinion, doesn’t always generate great art. It can generate art, but in the long run, I’d say it’s a fail point. When we made Déjà Vu, for instance, we weren’t conflicted with each other. I’d just lost my girlfriend [Christine Hinton, who was killed in a car accident]. I was a mess. Sometimes I would come into the studio and sit on the floor and cry. That was a little hard for everybody to deal with – me included.

“The music was the triumph there. It’s what held me together, it held us together, and it gave us what the French call a raison d'être. I needed a reason to stay alive, and that was it – music. When I got done with Déjà Vu, the studio was the only place where I felt comfortable, so I stayed in there. I had lots of songs, and so I made If I Could Only Remember My Name."

David Crosby talks songwriting, guitars and his new solo album, Croz

Record making today is so different from what it was back then. What do you miss about those days? The pace? The studios?

“Well, it is different today – that’s for sure. I like the technology that we’ve got now because it gives you so much ability. For instance, we couldn’t have made this record back then with no money. The couple of times that we had tracking sessions, we went into Groove Masters, but that was grocery money. And if my son hadn’t had a studio – he converted his garage into a high-grade studio – if he hadn’t had Pro Tools or Logic… I think we used Logic ‘cause we’re Apple guys… we couldn’t have made the record. I couldn’t pay for a studio.

“Also, I didn’t want to have a borrow money from a record company, which is essentially what you used to do. They would operate like a bank: They would advance you the money and then charge you 300 percent interest. We didn’t want to go that route. I can’t believe I pulled it off. When we finished, we looked at each other and said, ‘Wow, we did it – and it sounds fantastic!’”

How did you come to use Mark Knopfler on What’s Broken?

“You know, it’s the generosity of friends. A good friend of mine, Adolfo Galli, is a promoter in Italy – the best one, actually. He also promotes Mark there. So he said to Mark’s manager [in Italian accent], ‘You know, this David Crosby, he’s good. I think it would be good for him and Mark to make some music together.’ I spoke to the manager, who told me that Mark didn’t really do this kind of thing, recording with other people. But I said, ‘Can I just send a song, just to see how Mark feels about it? Because I would be so honored to be able to make music with him – ‘cause I love him!’”

David Crosby talks songwriting, guitars and his new solo album, Croz

Did you give Mark any thoughts or direction as to what you wanted him to do?

“Nothing. I just sent him the song with my thoughts high in the air. I didn’t try to prejudice the situation – you can’t make somebody like something. Nash and I are kind of the pros from Dover on putting harmonies on stuff – people ask us to do it all the time. I could list you 10 major records from the last couple of years that we’re on. And we love doing it ‘cause we’re good, and we love music.

“But we won’t do it unless we hear the song first and feel that it’s worth it. And it’s only for friends – usually, it’s only for friends. I mean, even for somebody like David Gilmour, who’s certainly master class, we hear the song first – and he knows that. So we listen to it and say, ‘Yeah, we could do that. Here, right here. Ohhh, I know exactly what to do there.’ And you communicate back and forth. That’s how it’s done at a high level.

“With my song, I heard back from Mark, and he said, ‘Oh, yeah, that’s a good song. I could do that.’ And he sent us back what you hear. It’s not just that he’s a great guitar player, great writer and great singer; he’s a master craftsman at building a record. He understands set-ups and pay-offs, how to make a thing swing, all that stuff. He knows! He’s really, really good at this. He did me such a solid – and I don’t even know him. He did it because of the music. That’s high level. That’s going for the high ground. And the result is a beautiful piece of music.”

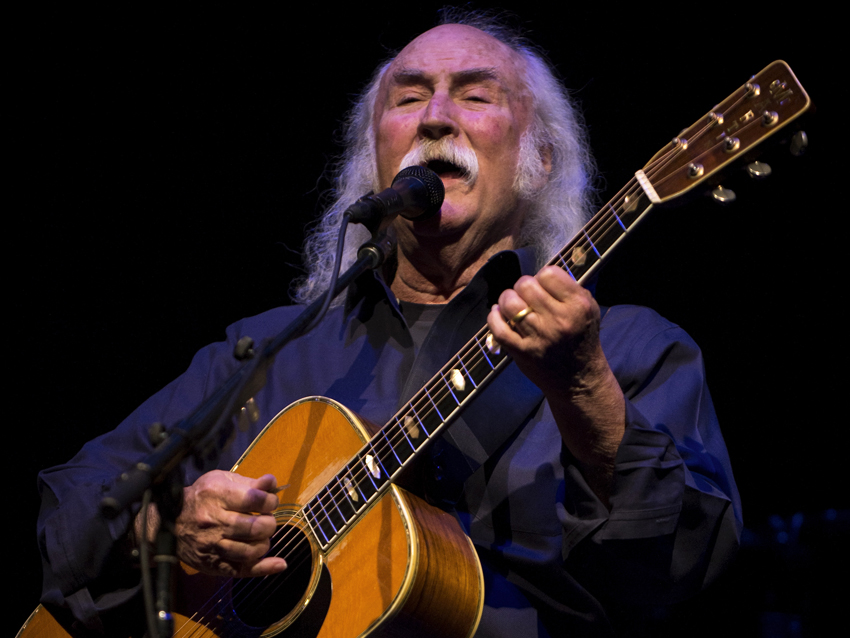

Holding On To Nothing is so sparse – it’s basically your voice, a guitar and Wynton Marsalis’ trumpet. Was that what you heard when you wrote it?

“Yeah. It’s probably my best vocal on the record. It came about in a wonderful way. There’s a poet who works in a bookstore where I live – really nice man named Sterling Price. He sends his poems out to friends. Sometimes they’re the size of haikus, sometimes they’re longer. With this one, I read it and I said, ‘Sterling, that sounds like the first verse to a song. Could you write me another? Same size, same rhyme scheme?’

“He sent me another one, and it was good. I said, “Do you have another one in you?’ ‘I don’t know.’ ‘Well, do you know what a chorus is? Let me show you – this is how it works.’ That’s how it developed. He wrote a chorus and another verse, and I made up the music to it. I sang it and it was really good. I played it for Sterling, and he burst into tears – he’d never written a song before.

“So I sent it to Wynton, and just like with Mark Knopfler, he said, ‘Oh, yeah, I could do something with that.’ The way he comes into the song, at just the right moment, that tone… I go deep on Miles, but I don’t think his tone’s any better than Wynton Marsalis. Wynton had some of the finest tone, and he made some of the best choices of notes – he’s got such taste. He and I are friends, but that didn’t affect him wanting to do this. It had to be a good enough piece of music for him to get involved.”

David Crosby talks songwriting, guitars and his new solo album, Croz

Speaking of tone, the sound of the electric guitars on Set That Baggage down is very classic CSN – the brightness, the jaggedness, a certain sparkiness.

“Well, that’s Shane Fontayne. He’s played for Springsteen, Sting… When I found him, he was playing for a guy who is arguably the best writer in the country, Marc Cohn. We stole Shane – I admit it. I hear what you mean about the sound. The sound is brilliant. Shane has that vibe; he’s a wonderful player.

“But again, it’s not about giving direction – it’s about getting the best guys, the best players. You get guys who are really deep, dyed-in-the-wool music guys. Then you sing them the songs, give them the words, but you don’t tell them what to do. You gotta let them feel what they feel and let them get involved. That’s how you get the best out of them.”

If She Called harkens back to Guinnevere –

“You know, everybody is saying that, and it’s totally different. It’s not in a tuning. The picking is the same, but it’s not even same pattern.

“The way that song happened, I was in a hotel in Belgium. I was looking down below me at this street of bars for tourists. There were these hookers workin’ the bars. They were like these cold, shivering, fox-faced little girls with skinny legs from Central Europe or some horrifying place where their parents got killed. They were trying to get these drunk, stupid guys to do it, and looking at them I just thought, ‘Where do they hide their heart? Where do they put their soul, their spirit and all the important stuff when they’re doing this?’

“That’s such a crappy way to earn a living, you know? Sure, it’s the world’s oldest profession, but it can’t be a good way to be; it’s a terrible path to be on. I’ve never been to a hooker, but I have a good imagination, so when I was thinking of that – ‘Where do they hide their heart?’ – the song just jumped out at me.”

David Crosby talks songwriting, guitars and his new solo album, Croz

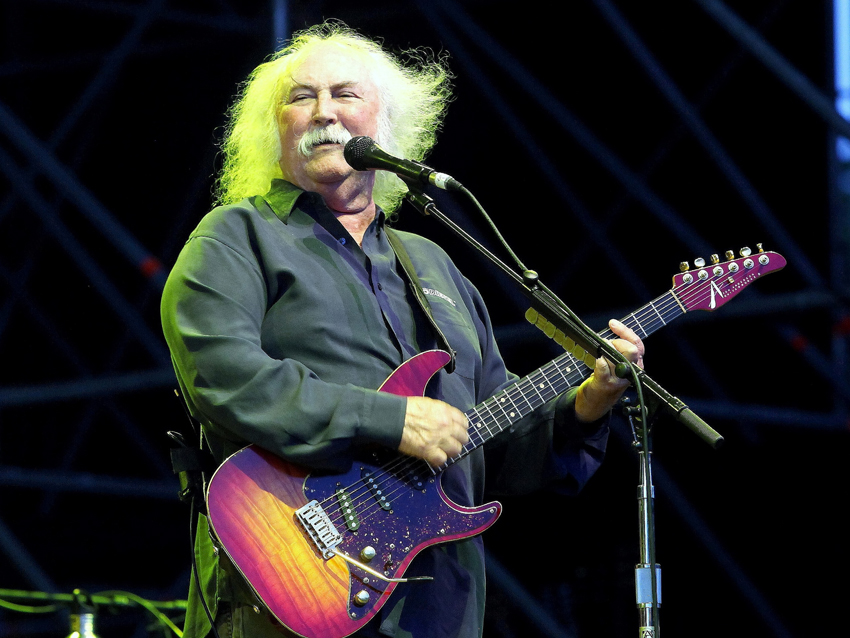

I imagine that you have a pretty nice guitar collection. What were the main acoustics and electrics you used on the album?

“I do have a pretty good collection, yeah. I used a really nice ’54 Strat on If She Called, but it’s not one of mine; I borrowed it from a friend, Albhy Galuten. It’s a beautiful guitar – very, very expensive. I have three really good D45s. I take them on the road, too. A lot of people won’t take their good guitars on the road, but I love these guitars and I love playing them, so I use them. I have a Gibson J200 that the Custom Shop made for me, a rosewood J200. The Custom Shop still builds some really fine guitars.

“On electric stuff, I typically play an Anderson Strat, a very fine, fine guitar. I have an Alembic electric 12-string, too; it’s probably 30, 40 years old. They made it for me… jeez, a while ago. I think it’s the best electric 12-string in the world, better than the Rickenbacker. I can’t play a Rickenbacker – the neck’s too narrow. Roger McGuinn can play a Rick because he could play banjo.”

Do you feel as though your guitar playing gets overlooked sometimes? You’ve played alongside people like Stephen Stills, Roger, Neil Young –

“No, I don’t. I don’t think about it. I’m happy with it [laughs], and it’s good enough to where I can write, which is the key thing. I can play medium-good rhythm guitar. There are guys who can do it better. That rhythm guitar player with Daft Punk – know what I’m talkin’ about? [Laughs] Oh yeah – he’s fantastic.

“I’m OK on the guitar; I try really hard. But I know that I’ll never be able to play as well as Stephen, not in this lifetime. I will never be able to pay as well as Neil, not in this lifetime. Or David Gilmour, to whom Fender should erect a monument, or any of the other great players – Eric! There’s dozens of them. I’m not competitive, though. I love playing electric guitar, but I don’t expect to be Jimi Hendrix.

“It’s funny: I sat right behind Hendrix, right behind his amplifiers. I snuck out in the dark, just before they hit him with a spotlight. This was at a place in LA – I don’t remember which venue. I leaned against his amps so that they were vibrating my chest. Wow! [Laughs] What a sensation.”

I can only imagine.

“He was a much calmer guy than you might expect – not flashy or showy or crazy in person. He was quiet and normal. What a talent. He was a deep cat.”

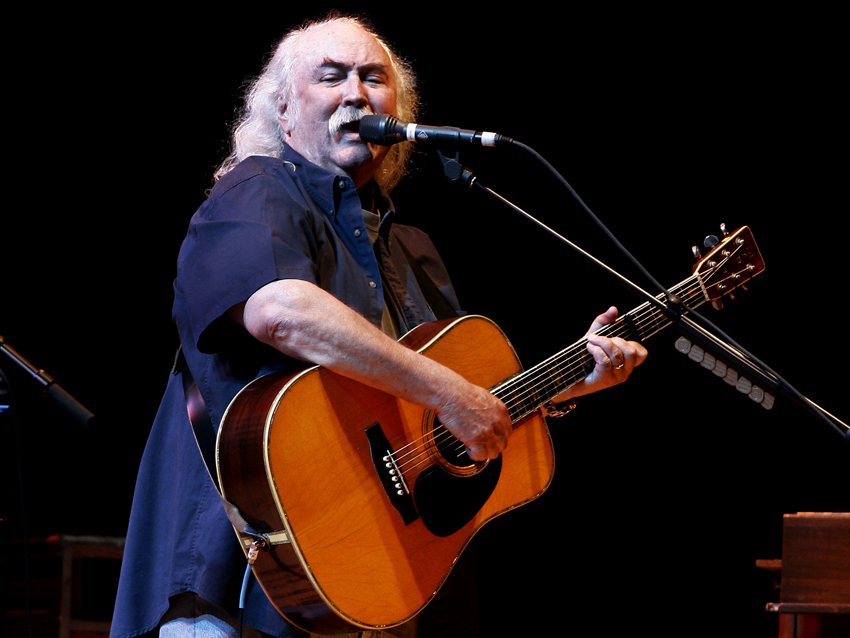

You’re 72 years old, but your voice is still remarkably intact. Why do you think that is? Granted, you haven’t always taken the best care of yourself.

[Laughs] “No, I… Hey, I’ve abused my throat massively, smoking things. I used to drink, a long time ago, but not ever the way real whiskey drinkers drink. I’ve never been a real drinker – I can’t handle booze. I don’t know how my voice works; I’m just lucky… and grateful. I work really hard to not abuse it. It’s fun, man.” [Laughs]

David Crosby talks songwriting, guitars and his new solo album, Croz

And then there's the way you, Graham and Stephen harmonize, which is still a thing of beauty. Do the three of talk about what you’re doing together, or is it just instinct?

“It’s very natural, it just comes. Graham is arguably the best harmony singer in the world. I think it’s me, but I say it’s him. [Laughs] He’s wonderful, and Stephen is very good at it. It’s a natural chemistry; we knew it the minute we heard it. Stephen and I sang a song, and Graham said, ‘Can you sing it again?’ We did and then he said, ‘One more time,’ and that was that. The minute I heard the three of us together, I knew what I was going to be doing. It was startling. We were at Joni’s house. Stephen is absolutely convinced it was at Cass’ house. [Laughs] It’s funny – he won’t give it up. After all these years, he won’t give it up, and he’s totally wrong.”

A few years ago, CSN shelved an album of cover tunes that had been started with Rick Rubin. Any chance you might revisit that idea?

“I think so. I strongly suspect that we’ll see that one come to completion. You know, we usually produce ourselves, but he’s a talented guy, so we wanted to see if it would work; we had to see if there was chemistry. We cut a few things, but there was no chemistry. He’s a nice cat, and he’s done an amazing thing with his life. This is a guy who was massively overweight, and he conquered it. Very rare.”

Graham told me that you guys wanted two Beatles songs on the record, but Rick only wanted one.

“Yeah, that was a bad thing. There were several that we were considering. When he told us there would only be one Beatles song, it was a little too 'I’m in charge.' It was too dictatorial; it just didn’t ring right. Because it was to be a mutual thing when you’re making a record. You learn these things."

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.