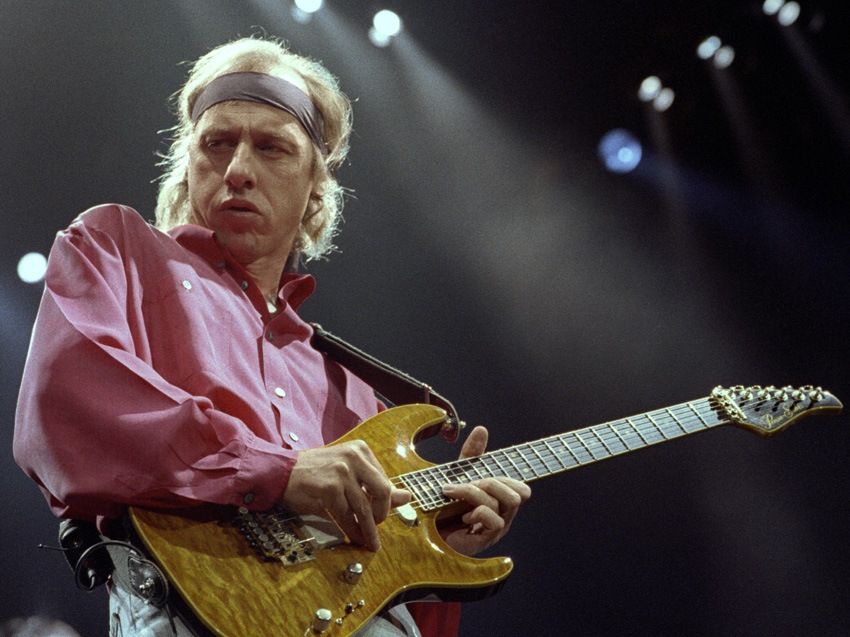

Back in 1995, Guitarist caught up with Dire Straits' enigmatic frontman to talk success, classic albums, playing the guitar with heroes and knowing "sod all about music".

Listening to the first Dire Straits album, it's difficult to detect the influence of the sound. It's not blues, it's not folk and yet both those elements play a part.

"I dunno," he whispers. "I suppose that's when I cut my teeth arranging. I didn't know anything about it, I remember thinking very differently when keyboards came into it. I started to think more seriously about basslines, chord inversions and voicings.

"I think I learned it the hard way - it helped doing a lot of folk stuff and solo acoustic stuff and then have a duo, then a four piece, then a five and then a six piece and so on; your ability to feel at home with a lot of instruments develops from time spent in the driving seat. Arranging doesn't faze me at all now but then I was kind of illiterate - still am in a lot of ways."

Dire Straits were one of the few bands who managed to fly in to face of punk, successfully finding a foothold in a music industry which had apparently turned its back on anything other than angry young men with an indifferent musical aptitude.

"I started to discover that the more you put on a record, the less you're getting out of it."

"There were a lot of little kids with bands, but there were two other things, don't forget: there was the Saturday Night Fever thing which was huge in that everyone was buying disco records and making disco records and then there were these big, pompous bands like Boston and Kansas and The Doobies were doing things like, it seemed to me, a big rock disco thing in some ways.

"I wasn't really interested in all of that, I liked the idea of little beat groups and a stripped down sound. That's just what interested me at the time, having this little group. I wanted a vehicle for the songs, but I wanted it to be stripped down.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

"You just go all around the houses sometimes and you just come to where you started in some ways. It's amazing really, by ignorance, but sometimes that audacity just works somehow. I can't listen to that stuff. I just won't. I never listen to any of it, ever. I listen to a bit of it when it's made, but..."

Continuing the train of thought about the 'little group' manifesto that Dire Straits championed in the early days, things had become a lot more orchestrated and big sounding by the time Love Over Gold was on the shelves. In fact, the album was scorned by some critics for being over-produced.

"I think it was," says Knopfler nodding surprisingly in agreement. "You just have to go through it and learn. I mean, what's happening is you're doing a lot of learning in public, artistically and technically.

"I remember doing things on Local Hero that I wouldn't dream of doing now; playing Ovations and putting them in the board - just ridiculous things. I started to discover that the more you put on a record, the less you're getting out of it.

"I've told this one before, but I was sitting in a bar once and unfortunately Telegraph Road was playing and I was sitting there thinking, Fuck, it sounds like this big lifeless thing. All this work had gone into it and it doesn't sound like it's got any life in it somehow. And then straight after that came Rave On by Buddy Holly. It sounded four times louder, 20 times bigger and with a hundred times more life. That really made my day."

At the time it seemed that the band's answer to the over- produced accusations was to record the EP Twisting By The Pool, a back-to-basics statement if ever there was one.

"Twisting By The Pool was just another bad idea," he says somewhat mournfully. "I didn't know anything about making rock 'n' roll records. You have to learn the hard way and that's all I can tell you really."

Brothers In Arms was a colossally successful album. There must have been a point where you realised that the album was growing legs and about to run marathons.

"No, no, not at all. I think it just happened to coincide with compact discs and it was a sheer fluke. If it hadn't been that album it would have been something else. It was just an accident of timing, it got connected - Brothers In Arms was the first CD single, or so I'm told and I suppose it was one of the first CD albums.

"That's all it was I think. Plus we had a couple of hits in America - Money For Nothing and Walk Of Life - so it got connected with the American success, but people will always want to make something like that into something else completely."

Surely you can't write off such a phenomenal success as simply something being the result of pure coincidence?

"When you're involved in something, you're so in the middle of it, that you don't share the perceptions which go on outside. I don't like being part of that vibe, I'm just happier to be on the inside. I don't go around saying, I've got a number one record all over the world, aren't I fabulous. That's never interested me.

"I like success very much because it lets me come into a studio like this and it lets me play Atlantis, but having said I like success, it's a completely different thing from saying that you like fame. Fame has got no redeeming features whatsoever; in fact if you wanted to make an equation, you could say that the price of success is fame."

It's clear that Knopfler finds fame a hassle…

"It can be, but I try not to let it get to me because I've never wanted to be babied. I go around the world on my own, go to the airport by myself and check into hotels and pay my own bills. I live like anybody else in other words. I go down to my own motorcycle and go backwards and forwards by myself.

"I don't like to be nannied, but I suppose that is because I was 28 years old when the band hit. A lot other people have to face it when they're 17 and they don't get chance to get involved in the responsibility of an ordinary life."

Over the years, Knopfler has played with so many of his heroes there can't be many that he'd still like to pluck the strings along with.

"It was great playing with the Everlys and The Shadows and everybody. It goes on, I suppose. I remember the lad in the studio, we were making a cup of coffee in the studio in Dublin before the session started, and he said, You know, that's the finest bunch of musicians in Ireland down there, and I said, I know. But I did think about it and it's quite thrilling really."

Interestingly, after the first wave of fame struck him, Mark decided to improve both as a guitarist and as a musician and he sought help through the pages of the Mickey Baker guitar tutor.

"It struck me that I knew sod all about music, so I thought I'd try and figure out a little bit more about it. So I just sat down and made myself stick at it, just like the man said in the shop.

"It wasn't easy, but then it just started becoming easier and easier and I realised that even if I couldn't always remember the name of something, then I would recognise the sound."

Guitarist is the longest established UK guitar magazine, offering gear reviews, artist interviews, techniques lessons and loads more, in print, on tablet and on smartphones Digital: http://bit.ly/GuitaristiOS If you love guitars, you'll love Guitarist. Find us in print, on Newsstand for iPad, iPhone and other digital readers

“Definitely one of the most unique pieces to come through our showroom”: It was left in a nightclub in '74, then “hidden in a closet for decades”, now Mike Bloomfield’s custom-painted 1966 Telecaster is up for sale

“There is still no power but we have survived”: Joe Bonamassa returns to Nerdville West, after LA wildfires threaten home and vintage gear collection

Most Popular