With the new lineup of The Smashing Pumpkins in place (the band includes drummer Mike Byrne, guitarist Jeff Schroeder and bassist Nicole Fiorentino), Billy Corgan is finally ready to take the group on the road this summer.

Having already dropped the first four of a planned 44 songs for the album Teargarden By Kaleidyscope, Corgan is, no doubt, thinking big. And when it comes to interviews, he doesn't hold back, either. In part 1 of our exclusive conversation, Corgan spoke voluminously about his approach to songwriting, his gear and guitars and the process of rebuilding the Pumpkins from the ground up.

In this, part 2 of our interview, Corgan is no less effusive - and revealing. Here he elaborates on the inspiration and recording of the first batch of Teargarden songs, offers his thoughts on alternative rock culture, the eroding music business (check out his Tweet in which he echoes the recent sentiments of Radiohead's Thom Yorke) and plots the course for the new Smashing Pumpkins.

Ready for a wide-ranging and fascinating dialogue with one of rock's true originals? Listen to the podcast below and read on for text of the interview.

The song A Stitch In Time is really gorgeous. Did it stay pretty close to your original demo?

"Well, all I really had was an acoustic version, and everyone agreed that was the way to go, to not turn it into a band song. For me, the challenge was, can we keep it feeling like an acoustic song, but can we produce it in a way that gives it some more emotional energy? And I really thought of someone like Donovan, who did a really good job of that. 'Cause he wrote a lot of his songs obviously on acoustic, and yet somehow his music was able to convey something a little more exotic.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

"I recorded a track and then I did the vocal, so we basically had the acoustic version of the song, and then kind of just futzed around with different ideas, different approaches, to try to come up with a different orchestration to convey an emotional value through the song. Yeah, it was a really fun process; it was interesting 'cause it was very trial-and-error. I didn't think it was going to turn out as maybe pretty as it sounds…"

It's interesting that you mention Donovan because there is a bit of a '60s vibe to it. Now, there's the sitar - is that an actual sitar or a Coral Sitar?

"It's a Coral electric that I bought somewhere in Florida along the way, but it's a '60s. One thing I guess I should point out, because we were talking about it earlier, a little about influences: Teargarden, for me, is almost like a person looking past, present and future all at the same time and trying to have that perspective."

"Part of my logic is that emulating and, at times, paying homage to artists that influenced me is, in a way, telling part of my story. So in the past, where I would have been much more egoistically concerned about whether or not influences could be spotted, because I wanted all the attention to go towards me or the band, as if we were creating music out of a vacuum, this, for me, is more like letting someone into an attic and saying, 'Here's the thing I built; here's the thing I copied; here's the thing I dreamed about that got discarded.'

"And so there are moments where it's sort of reflective in a kind of sentimental way, and there are times where it's wholly futuristic and is about abandoning the past. It's an interesting way to approach because it's much different than what I used to do."

Is this scary for you, this new way of writing, new way of recording, this new mentality?

"No, not at all. I'm actually really excited, because I think what happened with me is that we had such tremendous success in the '90s and, you know, I just kind of kept making up new rules and they kind of kept working. Well, at some point they just stopped working as effectively now. Somebody could say that's because I lost something, or things changed, or whatever happened - you know, everybody goes through those cycles.

"But I think what ended up happening was, the way my brain works is, I sort of abandoned the approaches that I had in many ways because I thought, OK, right, I've just got to get onto something else. I left a lot of threads that were lying there that were really good. The whole point through the '90s for me was to push boundaries and try to get somewhere new - and sometimes we did that and other times we really failed.

"I feel like I'm back in that headspace but not in shadow of the past. That took me a while. So what I was trying to say is, through the decade between 2001 and 2000-something, a lot of that time was about trying to wrestle with the shadow of what had been done in the past.

Performing A Stitch In Time at Record Store Day in Los Angeles last March

"For me, this past year has really been the first time…maybe it started with the American Gothic EP that we put out…it's the first period since the '90s where I feel like I'm not in any shadow anymore; I've let it go. You know, I've learned my lesson. I appreciate and honor what worked about it, and the parts that don't work, it doesn't bother me anymore. It's like, 'OK, time to move on.' I'm back in that space where I'm really excited. And I don't know what's coming around the next corner, but it's much better than living in that shadow of like, 'Well, should I do this because people expect that? Oh, no, they expect that, so I'm gonna do this to fuck with their heads.' I've let go of all that stuff."

When you came out with Gish, it was "OK, you're alt-rock - or you're grunge - and 'this' is expected of you. You have to sound like this and talk to these kinds of fanzines." Is it liberating that those restrictions aren't placed on your anymore?

"I think they're still placed on me; I just don't pay any attention to them. You know what I mean?"

Like what would be placed on you?

"Well, I find it really interesting where I'm still, in many ways, held up to what would be called 'alternative rock standards.' You know, the way I've marketed my music or the way I do certain things - I'm held up to a standard that all the subsequent generations for the past 15 years haven't been. So if somebody from American Idol does a cool commercial, those same people will write about how it's clever and funny - and look the other way for the fact that the person is selling their soul.

"Somebody like me is still supposed to represent some value that doesn't mean anything anymore. Personally, I wish those values could mean something. I wish there was a reason to uphold those values across the board culturally, because I thought those were good values to have. I think the values that great artists like Kurt Cobain and Neil Young and Johnny Cash all represented, those were important.

"I took a lot of inspiration from those artists, and many others, who had great ethics and great concepts of ethics; those are all gone now. Basically, people talk about the ethics, but they don't mean anything anymore. I still hear that and feel that, but it doesn't have anything to do with the survival and the future of The Smashing Pumpkins, which is ultimately what I have to be concerned about.

"So I'm happy to be in a place where I sort of just stuck my flag in the sand and said, 'OK, this is what I'm going to do for the next three or four years - like it, don't like it, it's cool. And because I've placed the core of my energy back on music, and not on all the other stuff I used to worry about, including having a dysfunctional band…or two…I feel like that's put me back at the center of my ethics - not somebody's opinion of what it should be like.

At the V Festival in Sydney, Australia, 2008. Image: © Bob King/Corbis

"I'm being more led by the spirit of what I'm doing than whether or not it make sense to some blogger somewhere. Most of those people aren't living in the reality that I have to live in, which is, you have a completely decimated music business; the labels that exist have basically turned into nothing but bread and cookie sellers. The creativity is gone, in many cases; and even if there is creativity there, they don't have the resources. The public has moved on to many other things. Music is no longer the central cultural guide that it was for many, many years.

"So, people like us still have to wake up and look at a bunch of rubble and figure out, 'OK, what do I do with this?' You don't have the ability to pretend you're new [chuckles] and play whatever new fantasy is going on. You have to sort of live with where you come from. And I'm…fine. I think one part of that, for me, is being willing to admit that I've made mistakes and have some real contrition about where maybe I was misguided, but maybe in my heart I thought I was doing the right thing.

"I'm just in a good humble place where I want to go back to being a musician. At the end of the day, I think the best way to judge an artist is, wait till they're done. And then, sort of add up the things that they did and you can decide whether or not their life was worth something."

Let's go to the last two songs you've posted so far. Now, there's Widow Wake My Mind, which has a great opening riff. Does a song like that start with the riff, or do you have the main section first?

"Actually, in the beginning I just had the two parts, just the [sings softly] 'Ohh, oh-ohhhh,' and then I had the chord changes for the chorus. A lot of times when I write something like that I think, Oh, that's a dumb song. [We both laugh] I do! I'll think, Oh, that's a silly song - and then, three days later, I'll be in the kitchen making a cup of tea and it's still in my head! So I try to listen to that part of myself. Yeah, I like that it has a cute charm to it, you know?"

Mike Byrne does some amazing drumming in the song. You had mentioned that you "guided," for lack of a better word, Jimmy [Chamberlin] on some of his playing. Do you find yourself giving Mike direction, or does he intuitively know what to do?

"He's…he's probably sick of hearing me talk. But I'm quick to point out that Jimmy and I had the same collaboration process. What Jimmy made sound so effortless was the result of a lot of talking and a lot of work, and really kind of focusing what the drums were trying to say. That's why Jimmy was so successful in so many different ways in playing an incredibly busy drum style and still having it be part of pop music.

"I like to think of our music as organized chaos. So what'll happen a lot is, I'll sort of explain to Mike, 'OK, this is the emotional feel we're looking for; this is the approach we're looking for. You go from there where you wanna go, and if you have a vision of somewhere else you want to go, we'll try that.'

"We'll sort of develop his ideas, then we'll go through them and say, 'That's working. That's a little bit…I know what you're trying to do…' I think it's been a satisfying process. It's starting to click in his head that his role is just as critical to how the songs come across. Everything falls under the microscope in our process."

He does sound organic in the song -

"Well, that's the beauty: He's playing very busy at times, but he's worked it out in a way that he's able to play like himself, play busy, and at the same time not subvert the song."

Lastly, we have - and you talked about this a bit [in part 1] - A Song For A Son. Was that written on piano?

"No, it was acoustic [guitar]."

Oh. What kind of acoustics are you playing these days?

"I have some really nice ones - '60s and '70s, and maybe even a few '40s and '50s. I think for that one I probably used a Gibson J-200, probably like a mid-'60s model, kind of the same one Elvis played, with the bigger body and the stripe down the middle.

"It's sort of like cook in the kitchen - I try to think of what tone I would want. I have this Epiphone acoustic, which is similar to the same model, without a pickup, that John Lennon played in The Beatles. It's very metallic sounding. I don't have a favorite one, because for me it's always about what's the right guitar for the song."

But you don't have so many that you can't figure out which one to use.

"Mmmm…[chuckles] I have more than I use, let's put it that way."

This might be a hard question: Are you taking about your childhood in any kind of way in the song?

"A song like that is interesting. When I wrote it, I didn't have anything in my mind other than sort of a feeling. It wasn't until I finished it and listened to it a few times that I realized that it had a lot to do with my relationship with my father. I didn't think that when I wrote the song, so that's why it's kind of weird to me. But that's what it seems to be about…something to do with legacies and, you know, what our fathers pass on to us. I like that it's sort of vague."

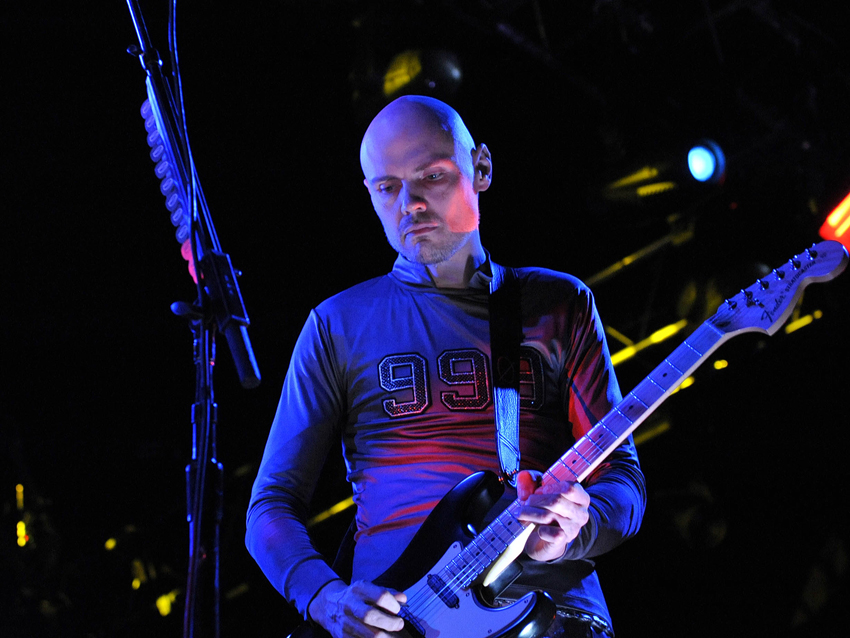

Corgan performing at the Hotel Cafe in Los Angeles in 2009. Image: © Jared Milgrim/Corbis

Is it harder to write a song like that and dig all of that out of your soul, or is it harder to talk about it once it's done?

"Sometimes it can be difficult if a song is triggering a particular set of emotions. I've never had difficulty talking about songs, other than I think that talking about them, in some way, sort of narrows [them] down. Because I know that I've listened to many, many songs and I don't know what the hell they're about. But they trigger a certain set of emotions in me that might remind me of going to high school or something.

"That's what the best music does: it gives you an individual experience without necessarily imposing the experience. If you think of a great songwriter, somebody like Neil Diamond, he was able to write songs in a way that you kind of felt like he was talking about you even though he was taking about himself. Whereas Neil Young is the type of songwriter where you really feel that he's talking about Neil, but somehow because he's talking about Neil he's really talking about you. [chuckles] It's different.

"Bob Dylan's always talking about someone else. You're never sure if he's talking about him or you. Everybody does it differently. I think my best songs, somehow I'm able to have them be very personal, but they don't turn off somebody's ability to find something personal in them. I've tried to write more impersonal songs and I find that people don't respond to them."

Like what? Example.

"I can't think of anything off the top of my head. But if I sing 'I' or if the song seems to be like I'm singing about myself or is related to me, that seems to work better for people connecting with the song than if I sing about 'you.' Bob Dylan always sings 'you.' Not always, but for the most part he's always [sings in a Dylanesque tone] 'Yooooou and yooooou.' [chuckles] And it works, you know? Because he's talking about somebody else…but he's really talking about you."

Last question: You said earlier [in part 1] that you feel this is the best lineup you've had. There are those, as I'm sure you know, that love and embrace the lineup you had in the '90s. They would call it the 'classic' lineup. Does that concern you, that some people will never be able to get past that?

"I've kind of let go of it. I've even said to fans that if we put that band up, I don't know how functional it would be at this point. That doesn't mean anything, I think, to a fan - and if I was a fan, I would feel the same way.

"I think the beautiful thing is that there are four or five records there, plus other songs, probably about 200 songs, that the band turned out. And there's a lot of video in the vaults and stuff that people can explore and really see what was good and bad about that band.

"Of course, I have a different experience because I was inside. But I totally get, as best as I can, why people were attracted to that band. That band had an interesting darkness to it that, when it was on stage, had an incredible electricity. I'm not sure why other than it just worked, and it worked basically from the beginning.

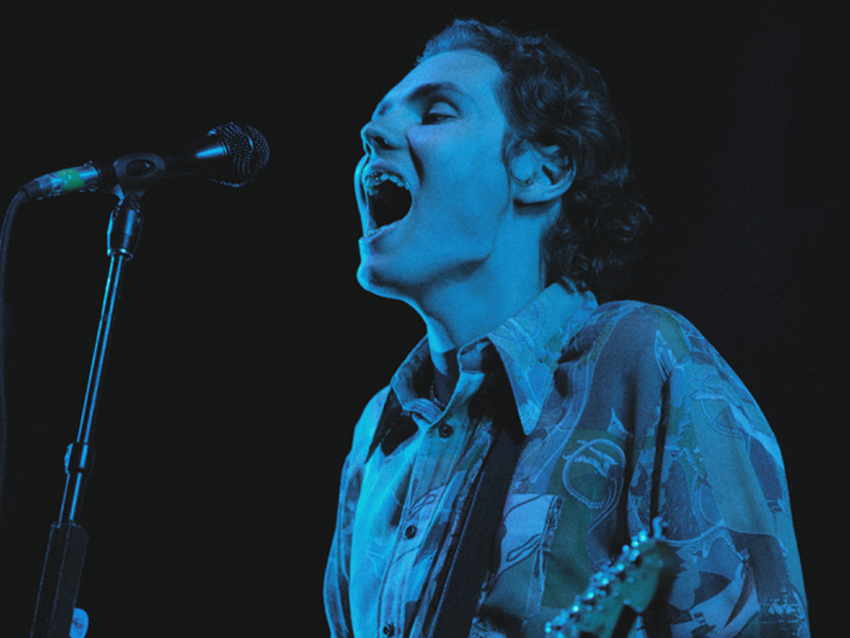

"I'm proud of the past," says Corgan, shown here on stage in 1994. Image: © Gary Malerba/CORBIS

"I would be careful to say that when one of the members left - when Jimmy left during the Adore period and then subsequently when D'Arcy left and Jimmy came back during the Machina period - I really felt the imbalance. It was not the same. It wasn't, like, 75 percent as good; it was, like, 50 percent as good. Something about not having the four people in the room."

"So all I can say is that I'm really proud to continue under The Smashing Pumpkins name. I'm proud of the past, and I feel the best way to honor the past is to be in the present. I always get really uneasy when the present is too much about the past, because the past wasn't about the past. [chuckles] That band, from 1988 to 2000 was very much about being in the moment.

"That's the only thing I would say to a fan: If it's good enough, great. And if it's not, or if it doesn't register in your mind what you need to hear or see, that's totally cool. I don't have any problem with that. Ultimately, music is a personal thing, and no amount of intellectual explanation is going to change that.

"I think if somebody gets hung up on strictly the lineup as an issue only, then that seems to be a little bit silly. But if you don't have a problem and you listen and you're not satisfied with what you're hearing, if it doesn't have same energy coming out of the speakers, or if you go to see the band and it doen't have the same whatever it was you liked about the old band, that's totally fair."

Well, I'm loving what I'm hearing so far, the first four songs…

"Great. Thank you."

I look forward to hearing the next 40. [We both laugh] This is going to take a year or two, right?

"I don't know. My general estimate is between three and four years."

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.