Adrian Smith on Iron Maiden's new album The Book Of Souls

The guitarist and songwriter on the metal legends' latest

Introduction

As Maiden do the double with their new album, we talk to key songwriter Adrian Smith [pictured, right] about playing by the seat of his pants in the studio and exactly what fuels his creative dynamic in the band.

A cold barren wasteland, cloaked in darkness and devoid of all meaning… No, sir. We don’t want to imagine a world without Iron Maiden in it. But we also can’t envision Iron Maiden without Adrian Smith.

Okay, fair enough, between 1990 and 1999 we had to deal with the harsh realities of a Smith-less Irons, but does anyone talk about the era that brought us Virtual XI with great affection?

The Eastender doesn’t just bring a special blend of the technical and the melodic to his playing, he’s had a hand in writing some absolute belters

Exactly. The Eastender who joined for 1981’s Killers doesn’t just bring a special blend of the technical and the melodic to his playing, he’s had a hand in writing some absolute belters, too: Wasted Years, 2 Minutes To Midnight, Can I Play With Madness, The Evil That Men Do, Flight Of Icarus, Moonchild, The Wickerman… You get the picture.

Now, for Maiden’s first ever double studio opus, The Book Of Souls, he’s contributed his strongest suite of songs since returning to the band in 1999, alongside sterling contributions from the band’s four other songwriters - big chief Steve Harris, vocal powerhouse Bruce Dickinson, and Adrian’s fellow guitar amigos, Janick Gers and old childhood friend Dave Murray.

“It was very, very spontaneous,” says Adrian of their soulful studio experience. “Some of the material, we rehearsed it and recorded it. We learned it while we were still using hand signals and eye contact. Kevin [Shirley, producer] would record it while we were rehearsing, so that section would have a really great feel, even if it was the fi rst time we did it. There’s just some kind of magic about that.”

Recorded at Paris’s Guillaume Tell Studios (like 2000 comeback Brave New World) before the news hit that Bruce Dickinson was suffering from head and neck cancer (the trooper has since beaten the illness), The Book Of Souls saw Adrian looking back with his writing style after The Final Frontier’s rather experimental excursions, in a way that fans of classic Maiden are going to love…

Winging it

How different was the process of making this album for Maiden, and how prepared were you going in personally?

“I was quite well prepared. I start about a month before we go into the studio, or before we even contemplate getting together, because usually we do a few sessions around each other’s places. I had around 10 or 12 songs on a CD. I think the rest of the guys had a lot of stuff.

I’m really pleased with the production. Sometimes I think our albums are a little too raw, a little too undercooked for me

“But we didn’t actually rehearse, and that was the big difference this time. Normally, we take two weeks and we set up all our gear in a rehearsal room and maybe do a song a day, maybe take six or eight songs that are finished. But this time, we winged it a bit, we had so much raw material.”

You recorded comeback album Brave New World at Guillaume Tell Studios, too. Does it have special memories for you?

“Yes, when we got there we were all pleasantly surprised, because it hadn’t changed a bit. They had the same carpet on the stairs in the rec room. The atmosphere felt great straight away. One of our better sounding albums is Brave New World and someone said, without knowing where it was recorded, that it sounded similar.

“I’m really pleased with the production on the album. Sometimes I think our albums are a little too raw, a little too undercooked for me. But I think this is a good balance of capturing the liveness of the band - because it is, virtually - and then giving it a little bit of a polish. I was pleased with that, but the only downside of going to Guillaume Tell is we realised it was 15 years since we’ve been there. It seems like five, which is a bit scary!”

Death or glory

There are five songwriters in the band. Does that mean the art of compromise is a constant challenge for Maiden?

“I think it’s got a little more democratic. Having said that, a band is always a compromise, but sometimes it can be good. Back in the 80s, Steve would bring in four or five top-to-bottom finished songs, but now he’s more interested in producing, arranging, lyrics and melodies.

I thought I’d try writing shorter songs, like 2 Minutes To Midnight and Can I Play With Madness, with just Bruce and me

“He’ll ask me what ideas I’ve got and I’ll usually have pretty well-formed ideas. He gets me to play my ideas to him and he’ll come out with a melody straight away. He’ll sing the melody over the top and he’ll record it. Then, down the line, he’ll sort through it.

“But he’ll say the first thing that occurs to him is usually the best, and he’s got a lot of ideas for lyrics, so we’ve done that quite a bit over the years. Well, I say over the years, in my second stint in the band - in the last 10 or 15 years, that’s the way it works.

“This time, I did a couple of things with Bruce, too. I thought I’d try writing shorter songs, like 2 Minutes To Midnight and Can I Play With Madness, with just Bruce and me. We haven’t done that since I’ve been back in the band. Maybe with Wickerman, we did it. So that was different. He came over before we started recording and we wrote Speed Of Light and Death Or Glory.”

The great unknown

You developed a more progressive and darker style when you returned to the band, so it’s interesting that you consciously chose to write in that punchier style again, because your tracks seem crucial to the balance of the album…

“Yes, exactly. I thought maybe we’d have two or three punchy songs and then we’d have a couple of long ones and it would be more of a stripped-down album. But, of course, that’s not the way it turned out. In fact, it was totally the opposite.

The Great Unknown’s riff is in open D. But I also used a capo on it, which makes it weirder, and I’m dreading playing it live

“But, like you say, the shorter songs give it the balance. Plus, I did do a couple with Steve that are longer pieces, really. So there’s a bit of everything.”

The Great Unknown definitely reflects yours and Steve’s styles. How did that track come to life during recording?

“I was messing around with a tuning, an open D tuning [DADF#AD]. You can play interesting picking patterns and you can also play solos. I forget what [other] song it is, but I used it on a solo.

“It sounds very strange, but it kind of works. The Great Unknown’s riff came out of that tuning, really. But I also used a capo on it, which makes it weirder, and I’m dreading playing it live [laughs]. But that’s a different little thing I did on this album.”

'Maiden moves forward

It feels like you’ve been instrumental in pushing the band into new musical areas in the post-Brave New World era…

“Yes, I think on the last album [Final Frontier] I brought in a lot of ‘strange’ time signatures, a lot of sevens. To be honest, we didn’t really embrace it like I thought we would. I don’t think it really gelled. We’re not proggy to that extent, like when you hear Dream Theater - we’re sort of on the straighter side of proggy, if you like.

Some of the stuff Steve comes up with is just not in the book at all... you’ve just got to watch him a lot of the time

“Though some of the stuff Steve comes up with is just not in the book at all. With a lot of his stuff he talks about a breath here and there, so you’ve just got to watch him a lot of the time. He makes up his own rules, which is great, but sometimes it takes a while to figure out what he’s driving at.”

How do you manage to push the band into new areas, while still satisfying people’s expectations of Maiden?

“Well, Steve constantly surprises me. I think the first time was when we did a song called Wasted Years [written by Adrian for 1986’s Somewhere In Time album]. I was messing around with a little four-track and I’d just put that riff down for Wasted Years.

“I was playing Steve some other stuff and I played it to him by accident and he said, ‘What’s that?’ I said, ‘You probably won’t like this as it’s so commercial,’ but he really liked it and insisted we do it.

“So something you’d think he wouldn’t want to do, he does. But I do like to sit down and visualise us doing different things. Obviously, we can’t do anything too drastic but whatever works, really.”

Working at speed

Speed Of Light sounds like it has a nod to your love of Thin Lizzy, as the lead work is quite Celtic, even by Maiden’s standards…

“Yes, that is a lead scale I’d been messing around with. I’ve rediscovered the pentatonic and I was listening to a lot of really good players and I noticed a lot of them were using these scales, even Eric Johnson and people like that.

“If you do them in a certain way, they can sound really good and really to the point. So I was messing around with that and it’s a variation on a pattern. I got that little riff out of it. A very catchy little riff, not the main riff of the song, but it’s in the bridge.”

I’ll think to myself, ‘Dave’s only taken 20 minutes, I’ll see if I can do it in 15!’ There’s a little bit of competition

When you, Dave and Janick are tracking back-to-back solos in a songs, do you get the chance to reflect on what the previous player has done before you record?

“Well, it depends, actually. Usually Kevin doesn’t play what’s gone before - it’s “just do it” - but you get a situation where Davey will go in and I’ll be sitting there having a cup of tea. Then he’ll come back in 20 minutes later and say, ‘I’m done. They want you in the studio now.’

“So I’ll think to myself, ‘Dave’s only taken 20 minutes, I’ll see if I can do it in 15!’ There’s a little bit of competition, which I don’t know if it’s a good thing - but that’s the atmosphere. It’s a very much a performance thing.

“I think in the old days, we used to sit there and get very creative with the solos, and spend ages doing them. But these days… Kevin likes to work very, very fast. I’m still plugging my amp in and he’s sitting there, waiting for me! So it’s pretty much seat-of-the-pants stuff.

“Sometimes I have to fight a little bit, because I want to try different amps and try something different on the recording. Sometimes I like to say, ‘Hang on a minute, I want to try this.’ And you have to fight for it a little bit. But sometimes it works out well.”

Spontaneous solos

It sounds like it’s pretty improvisational on the solo side…

“Again, it’s very much like a performance thing; it’s not something you piece together. So the solos that I do are always kind of spontaneous. Although I do have a couple of cornerstone ideas in each solo that I’ll go to and do some different stuff in between. Again, the early takes are usually the best. The more you try and think about it and work it out, the less effective it is.”

In the old days, were you a lot more methodical about solos on the whole?

In the last 10 or 15 years, I’ve studied the guitar more and become more secure in my technique

“I think I was, but I think I didn’t have as much confidence in myself as I do now. I spent my formative years as a singer playing guitar, playing the odd solo and a bit of double lead.

“It wasn’t until I joined Maiden that I had a lot more solos. I didn’t have any training, I didn’t really have a mentor. There was no YouTube then - you couldn’t see what people were playing, you have to get along as best you can. But probably, in the last 10 or 15 years, I’ve studied the guitar more and become more secure in my technique.

“I’ve studied more technique and practised more, so I’m a bit more confident in the studio and I don’t have to work every single thing out. But I like to have a few cornerstone ideas.”

Making the guitar sing

So, are those cornerstones hooks in a way? Because that’s always been a trademark of your solos…

“Yes. I wouldn’t consider myself a virtuoso that can just reel off stuff at the drop of a hat, though; I have to work at it a bit, obviously. But I suppose my brain is wired up quite musically, because I started off life singing more than playing guitar, so I do have quite a melodic sense.

I hear young guitarists now who are just incredible technically but could do with a little - I think - reigning in and melody

“I try to get that in my playing. And I hear young guitarists now who are just incredible technically but they could do with a little - I think - reigning in and melody. If there’s a little bit of flash in there, so much the better.”

Do your roots as a singer continue to inspire you as a player and songwriter?

“It probably shaped my style. Up to the age of 23, I was singing and playing at the same time [Adrian’s pre-Maiden band was called Urchin]. It’s almost a blues thing: playing it like you sing it, like BB King.

“I was very into ‘second-generation’ blues players when I was growing up, people like Pat Travers, Johnny Winter, Gary Moore and obviously Thin Lizzy with Gorham and Robertson. Quite bluesy really, rather than shreddy metal, although I did love Blackmore. So that’s shaped my style; I suppose that’s my natural rhythm. Once a person learns how to express themselves, that’s the way they play.”

And finally... Pants of death

The strange story of Adrian’s wandering phone full of riffs...

“I’ve got tons of song ideas on my phone. But it was a bit embarrassing, really, because in America we do runners from gigs, so we jump offstage, jump straight into the cars and go haring off, and we stop at a gas station or a lay-by and change in the dark on our way to the airport.

There’s me sitting in my underpants in a hotel room on video singing and playing guitar!

“It sounds crazy, but I actually lost my phone in America doing that and it was full of ideas. I had no password on my phone, so this guy found it and he went through my ideas, and there’s me sitting in my underpants in a hotel room on video singing and playing guitar!

“But I got a letter [from him] and he sent it back to me. He said he was a fan and said he loved my little performances on the phone! Of course, I thanked him and sent him a load of merch.”

Don't Miss

Rob is the Reviews Editor for GuitarWorld.com and MusicRadar guitars, so spends most of his waking hours (and beyond) thinking about and trying the latest gear while making sure our reviews team is giving you thorough and honest tests of it. He's worked for guitar mags and sites as a writer and editor for nearly 20 years but still winces at the thought of restringing anything with a Floyd Rose.

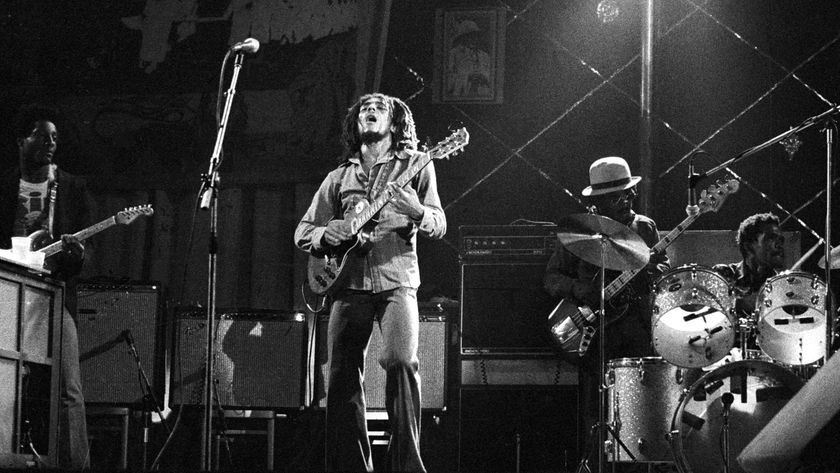

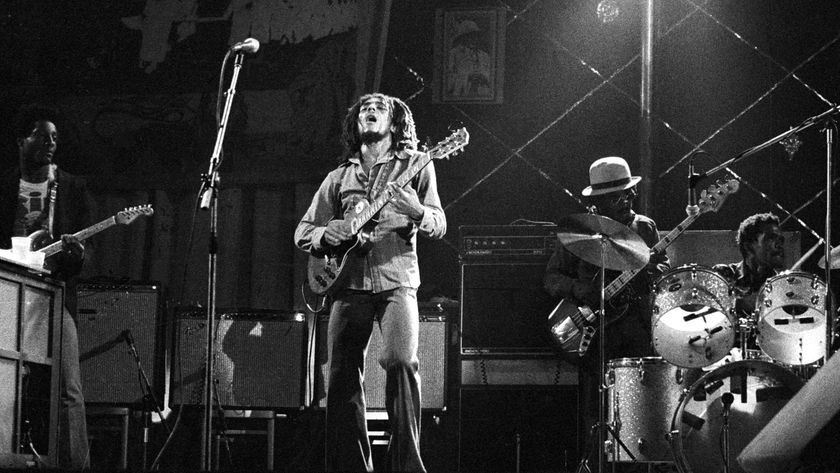

"Reggae is more freeform than the blues. But more important, reggae is for everyone": Bob Marley and the Wailers' Catch a Fire, track-by-track

“Part of a beautiful American tradition”: A music theory expert explains the country roots of Beyoncé’s Texas Hold ‘Em, and why it also owes a debt to the blues

"Reggae is more freeform than the blues. But more important, reggae is for everyone": Bob Marley and the Wailers' Catch a Fire, track-by-track

“Part of a beautiful American tradition”: A music theory expert explains the country roots of Beyoncé’s Texas Hold ‘Em, and why it also owes a debt to the blues