Nicko McBrain: Book of Souls, big kits, jazz vs metal and ticking off AVH

Larger-than-life Iron Maiden drummer opens up as band hits the road

Intro

Few bands make it to 16 albums in this, or any other, age. And those that do would be forgiven for winding down as they hit such a milestone. With their latest, Book Of Souls, Iron Maiden have proven they’re not any old band.

The album, their first since 2010’s The Final Frontier, sees Maiden, and particularly larger-than-life drummer Nicko McBrain, pushed to their limits. It’s a 92-minute double-disc effort, for starters. Then there’s the fact that, as the band’s collective age ticks up and up, the song lengths go along with it.

The record’s longest track weighs in at 18 minutes, and this is no walk in the park – this is an album filled with rapid fills, hard and heavy beats and bass drum work that you’d need a right foot like a rabbit’s to keep up with.

While many bands have come and gone since Maiden’s debut in 1975 (just think for a second how many musical fads have passed along the way since then), the Brit survivors are still standing and are arguably bigger than ever, still able to headline just about any stadium you could care to mention from all corners of the globe.

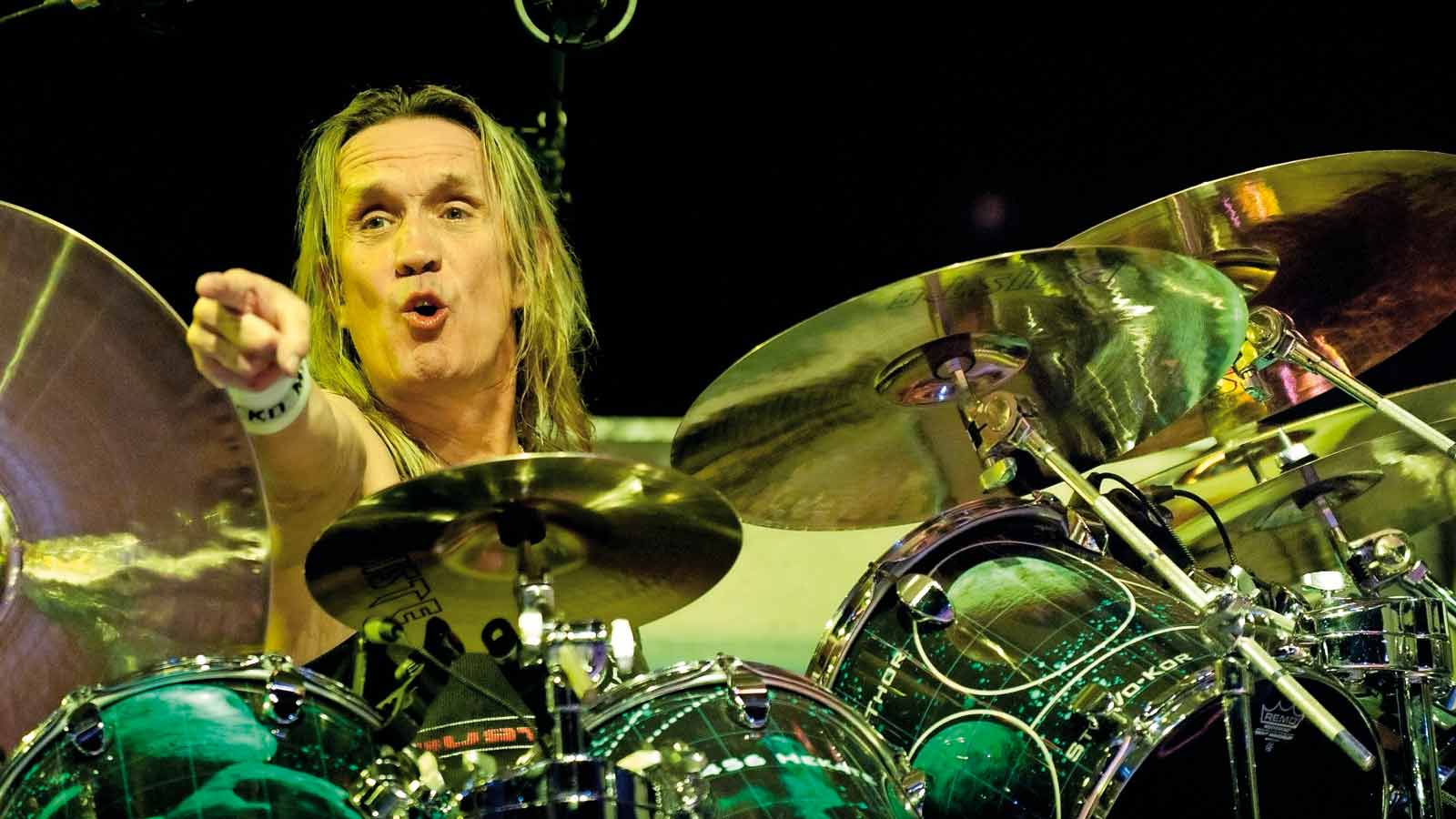

So it’s fortunate then that Iron Maiden have Nicko McBrain behind the kit. Now on Maiden album number 13 since replacing the now sadly deceased Clive Burr in time for 1983’s Piece Of Mind, 63-year-old Nicko remains at the top of his game. He seemingly eases his way through energy-sapping two-hour shows, mammoth recording sessions and just about anything else that is thrown at him.

It’s not just his incredible staying power that sets Nicko apart. He’s also an innovator, a man that has carved his own path rather than following the pack. While every man and his dog was filling metal tracks with double bass work, Nicko got his head down and powered Maiden’s pummelling metal with a single kick thanks to his frighteningly quick bass pedal technique. Similarly he’s a dyed-in-the-wool acoustic man, no sign of any triggers here.

Speaking of gear, there’s a topic Nicko knows a thing or two about. While some are happy for their drum tech to deal with the ins and outs of their set-up (and Nicko has a Grade A tech in Charlie Charlesworth), Nicko knows every inch of his kit.

As he basked in the early morning sunshine at his Florida home, we chatted at length about the return of Maiden, and also how he brought the jazz into metal, why he gave Alex Van Halen a ticking off, and whether the end may be in sight.

The Book of Souls

Five years away and you’ve returned with a double album, that’s not bad going…

“It’s 92 minutes long! It’s like a whole gig! It’s a great testament for younger bands coming up. They can look at Iron Maiden and the Stones and see the longevity. You can see the passion that we still have in playing with each other and the enjoyment we get sitting in a room making a piece of magic.

"When we sat back after finishing the tracks and asked Kevin Shirley how long the album was and he said it was 92 minutes, we were like, ‘What?!’ Bruce [Dickinson] said, ‘Well it’s a double album, that’s what it’s gonna be.’ I regard it as a triple album because I’m old school. I’m a vinyl man.”

"I regard it as a triple album because I’m old school. I’m a vinyl man.”

You’ve got songs of 18 minutes here, you’re not making it easy for yourselves as you get older.

“I know! But then at the same time we were all so excited when we were sat in the studio, Adrian [Smith] came up with ‘Speed of Light’ and we all looked at each other as he started the riff and we all wanted to work on it. It got our juices running because we knew it was a ‘1, 2, 3, 4 head down meet you at the end’ track. It was straightforward without complicated parts.”

That one may not have a complicated part but it does have a hefty dollop of cowbell…

“For the first month we were just writing, and then Kevin arrived and we went into record mode. We had learnt the song and we just wanted to go and record it. We went for it. We put the headphones on and I came in with the cowbell, there ya go! And the guys thought it was brilliant.

"The little drum fill in the intro, it’s not exactly what I wanted to play. I wasn’t familiar with it because we had just learnt the song – it was just, what you hear is what we did on the first track. We just flew through that track. We were so excited.

"It took me back to being a kid in the front room playing something, and when you got something right you thought it was great. We still have that adrenaline buzz. Some of my drum parts the guys thought were brilliant.

"On this album we analysed everything as a band. It was the first time we have sat down in the control room after putting the tracks down. Sometimes we’d do two or three versions and we would analyse each other’s parts. It wasn’t contrived, it just happened that way, and every one was critiquing each other’s playing.

"Ninety percent of it was complimentary, but then the other 10 percent might be, ‘Oh you sped up a bit here Nick.’ We analysed it all. It was a wonderful experience.”

You were back in Paris again at the same studio where you recorded Brave New World in 2000. How was it to be back there?

“Brave New World was our resurgence, with Bruce and Adrian coming back to the fold. When we went there nobody knew about the studio. We got there and what an album – the sound was stunning and it was the first one we did with Kevin.

"When it came to 14 years later, we knew we would do another record three or four years ago. I wanted to go somewhere warm because I’m a wuss that has lived in Florida for 25 years. But it was too far away, Bruce needs to be home for his flying activities, so it seemed more sensible to do it closer to home. Kevin mentioned Guillaume Tell and we went, ‘let’s go there’.”

The band is clearly comfortable recording in that studio. That vibe really comes across on the album.

“We walked in and it was just the same – what a great vibe. It was like putting on an old pair of slippers. I think that shows in the songs. Steve and the guys excelled themselves in the composition of the songs.”

Studios and BIG kits

You’ve worked with producer Kevin Shirley for several albums now. How does he go about getting your kit sound?

“It’s the same old. I think Kevin got the cauliflower out of his lugholes! I go in the studio, I tune my drums, he puts the microphones on them and I sit and play. Charlie my tech will sit in there first getting the levels.

"I sit with Kevin and do a bit of tweaking after the heads have settled in. We’ll record and I’ll sit with Kevin and say, ‘I don’t like that, there’s too much mid range there, I don’t care for that.’ One of the drums might be singing when it shouldn’t. There’s nine toms up there so you can hit the 10" and the 15" will start making noise. I had to fine-tune it.

"This digital age is quite open to just letting your drums do what they’ve got to do. They’re an acoustic instrument, you can’t start fiddling around putting tape over them and stuff like that. The kit isn’t the easiest thing to record.”

It sounds like you know what you want. Are you especially hands-on with getting the kit to sound exactly the way you want it in the studio?

“In terms of me being hands-on it was more like, ‘Do you like that?’ ‘Yes I do.’ Then off we went. I’m quite hands-on. I don’t twiddle the knobs or anything though. Once you get your levels it’s simple. The compression is different on some tracks, on some it sounds more close-miked. On ‘Empire Of The Clouds’ there’s a wide-open room sound with a lot of ambience to it.

"The toms on ‘Red And The Black’ sound like the microphones are closer to the drums, they’re not as ambient. I like that about this record. The drum sound doesn’t change, but the texture does.

"Sometimes when you use a maple drumset with a lot of large toms the sounds can blend into one another a little bit. You have to watch that. That’s just the nature of that wood. If you took a beech kit it would sound more brittle.”

The title track has some real drum moments in there, including the unexpected off-beat china pattern.

“The old kick china! That was what the track needed, it felt right. Dare I say it was Bonham-ish. I had that in my head, I was thinking what JB would play on it. I thought he’d whack a china on the off beat, so that’s what I did.

"The guys looked at me when I did that. I used a 22" heavy china on that, because of the compression it almost sounds like an 18” china, it’s got a texture to it like a china-hi hat. It’s very quick. I think maybe Kevin did that because there was a little bit of ringy going on across the rest of the kit because I was hitting the s**t out of it.”

You’re known for your huge kit – nine toms and god know’s how many cymbals. Are you still looking to add more?

"I’d love to put some more cymbals up, I’m a nutcase for cymbals."

“There’s nowhere to put anything! But believe me I’ve thought about it. You know us nutty drummers are always thinking of adding another snare here and a timbale there and a couple of something else and a bunch of chimes.

"On the last tour when we did ‘Can I Play With Madness’, for the middle bit there’s a cowbell section and I’ve got nowhere to put it because of how the kit has progressed. I used to have the cowbell coming straight off the bass drum. Then I had to bolt it to the hi-hat stand. Now there’s nowhere to put anything!

"I’d love to put some more cymbals up, I’m a nutcase for cymbals. I love cymbals, I love the top end of a drum kit. I’ve had a look and thought I could go up like Mike Mangini. But then what’s the point? It’s hard enough playing a nine-tom kit. For me, at my age, getting round to the 6" tom, I have to think about it before I go round there and hit it. When I was younger I just did it.”

The big kit must give you greater tonal options in the studio.

“Without doubt. It’s nice to have different parts of the drumset you can use – you’ve got your high and low tone toms. That’s just me. I’m comfortable with that for Iron Maiden. To be very honest with you I’d prefer to play a five-piece, I learnt my trade on a five-piece, well actually I learnt on a three-piece.

"As I started doing studio work I had a five-piece Hayman and I played everything flat, even my cymbals. I got a bo**ocking from Paiste for that because I used to crack all of these cymbals because I had them flat.

"When I sit in my restaurant and have jams with my chums I play a four-piece and I just shred on it. There’s not much to think about. Sometimes with having a bigger drum kit you over-think things, and you can over-play because you think you’ve got to hit everything.

"That was my mentality many years back. I’ve matured now. I’m like a good bottle of red wine, I’ve matured. Sometimes it can be a bit corked, but you never know.

"Because I’ve been playing a kit of that size since 1976, the cymbal configuration has changed but that’s it, that is my style of playing – especially with Iron Maiden. I don’t think Iron Maiden would work with a smaller kit.”

You’d have to remove some of your trademark tom fills for starters…

“On one of the songs there’s a little tom motif. When we were learning it I was playing it on the foot, 13" and 14" and Steve suggested moving it up to the 10" and 12". Little things like that, if I didn’t have the big kit I wouldn’t have been able to do that. The tonal textures spring into your mind. I can dynamically change a fill by switching say from the 10" to the 8".”

Is there anything to be wary of with having such a big kit?

“You get these sympathetic harmonics coming out so you have to be careful. It’s an acoustic instrument. It breathes and you want to hear it. If you play the snare it will sound differently from where you are to where say Steve is stood when he comes up to me and moans while we’re playing.

"Nah, he doesn’t moan, we have a laugh – but sometimes he’ll give me a bo**ocking and tell me I’m playing like an old man. My answer is always it’s because I am an old man!”

You’re a big exponent of a natural acoustic kit sound, aren’t you?

“You don’t want to start taping things and take the ring out of the drums. Steve always says my snare sounds like a biscuit tin, but everything on my drums is wide open. When you have a great producer like Kevin they don’t threshold and gate everything.

"Gating them is a lazy boy’s way out. Everything speaks to each other. Sometimes I feather the bass drum with a dynamic low beat. If I’ve got a threshold on it you won’t hear it. Same with ghost notes on the toms for a fill, I do those and you won’t hear it if it’s gated so the microphone isn’t open enough – it has to be wide open.”

You have an iconic single bass pedal set-up and style. How did that develop down the years, and why didn’t you ever go to a double bass pedal?

“Primarily that developed from the different bass players I’ve played with. It was never a thing of mine to see how quick I could get with one pedal. I wasn’t ever a double bass drum person. When I was growing up the only double bass drum players were people like Louie Bellson, Ed Shaughnessy and people like that.

"Then in the ’60s it was Cozy Powell and Ginger Baker. We didn’t have many fired-up double bass drum players. There wasn’t the massively fast thing going on like we hear today. These guys today are amazing. People like Mangini, what’s he doing?!

"For me my technique developed from locking in with great bass players. My style took that route, playing with the bass player instead of playing ‘2’ and ‘4’. I did a lot of embellishments and my drumming was more percussive in the early days. I played in three-pieces a lot like with Pat Travers.

"In that three-piece you have to fill in the gaps, you can’t just sit on a groove because it needs that percussive feel like Ginger played with Cream.”

Style, no triggers please and dreaming of The Royal Albert Hall

Before Maiden you played on the session scene, doing everything from jazz to funk gigs. Did that have a big impact on your playing in Maiden? These parts aren’t just straight metal, there’s a lot more going on.

“Exactly, it’s a mish-mash – thank you for noticing. That is my style. Originally when I was growing up it was the Stones, The Animals, people like that. Brian Bennett, Ringo Starr, Charlie Watts were my influences. It was simple poppy stuff. And then The Who came along and John Bonham and my whole life changed. I was into big band and funky grooves, I loved to play funk.

"My style was based around that, that music of the ’60s when I was growing up and learning to play. Then I played in blues bands and I started getting heavier, I always played hard. I learnt my trade and I loved these funk grooves. As my life progressed and I played with other bands like Streetwalkers. A lot of those tracks were melodic rock tracks, but there was a lot of funk in them.

"A lot of the influence there was from the guitar player Bobby Tench. When I got into Maiden the next progression of having played with Pat and people like that meant that I was still playing with those influences, and I brought that into Maiden. I think on this new record you can feel and hear those influences in my playing.”

"The only person I respect who plays an electronic drum kit is Rick Allen"

Another common theme in modern metal is the use of triggers. Where do you stand on that?

“You know what, my thoughts are that we play an acoustic instrument. If you’re going to play electric drums play f**king electric drums, don’t put them on an acoustic drumset. Why would you do that? Why would you play an electronic trigger on an acoustic drum?

"You can’t tune it and the bloke out front hasn’t got a decent set of ears or he’s a lazy bastard and he gates everything so you end up with a s**t sound. I’m old-school.

"The only person I respect who plays an electronic drum kit is Rick Allen. It works for him because he’s only got one arm and he uses his feet as another arm. That works. If you’re going to play in a band like Kraftwerk use an electronic kit.

"I bollocked Alex Van Halen about this because he triggers everything on his drumset. I’m not sure if he does his snare. I asked him why he did it because he had a beautiful kit. He said it was so he was consistent every night, that is his sound. I can’t argue with somebody’s opinion but for me, no thanks.”

Iron Maiden continue to flourish today while tonnes of metal bands have come and gone – why is that?

“It’s the quality of the musicians. They’re all amazing and I am so honoured to be along for this ride, that I am the chosen one for the drum stool. They are all virtuosos. The songwriting on this new album especially is off the charts.

"The guys step it up every album. We have that passion for playing and being together as a band, that’s where we live and breathe and what we have in our hearts. The drive and ambition has never changed. That is the winning formula. We have worked very hard and the morals and principles haven’t changed from day one.

"We also have Kevin who is the seventh member of the band, and then we have Rod Smallwood and Andy Taylor. Without them I don’t think we would be where we are. It’s a team effort. We care about what we do, we do it for us, it’s very selfish. We do it for ourselves and think the fans will like it and if they don’t, too frigging bad! It sounds callous and we do think of the fans, but we do it for us.”

How does it feel to be looked on as an innovator in your instrument?

“It’s passing the torch. It’s like when I think back to my heroes. Like I knew Keith Moon and had the opportunity to tell him that he was a hero of mine – he told me to shut up! We became chums. The best accolade in this game is when a kid comes up to you.

"I met a four-year-old boy a couple of months ago and he came up to me and said I was his favourite drummer. That meant so much to me. It can be a four-year-old, a 14-year-old, a 44-year-old, it all means so much. When you hear your peers in the business say things, that is great.

"I was with Thomas Lang a few years ago and he said he was a big fan of mine. He said he used to listen to me all the time when he first started playing. There was Thomas Lang, this phenomenon telling me he was a fan of mine. I thought, ‘What the f**k, you can do with one hand what I’ve been trying to do with two for years!’ It’s wonderful to know that you have influenced people.”

You’ve played just about every stadium in the world with Maiden, what’s left to achieve?

“The Royal Albert Hall. I always wanted to play there. I thought if I had made a record and played at the Royal Albert Hall by the time I was 25 then I would have made it. That motivated me. I’ve still not played there.

"I don’t think there’s any way Iron Maiden could play there, we’re too much for it. It’s a small gig, maybe 5,000 people, but for me that was like the Americans wanting to play Carnegie Hall – I have played there. I’d like to play in China as well. I’ve always thought China was a great untapped market for metal and for Iron Maiden, Maybe one day we’ll get there. That’s two things I’d like to do before the good lord says, ‘C’mon son, it’s your time to come up here.‘”

Speaking of which, you’re now 63 – how long do you can you go on for, playing this kind of intense and energetic music?

“We had such a great time on this record. Some time next year there will be a tour. I’m the twilight of the band, I’m not a granddad but I’m that age where people wonder how long I can keep going. If we’re going to make music like Book of Souls, who knows?

"As long as we have our health and we can still get up and do it then we will. We won’t ever become a parody of ourselves. If we can’t rock out and pay ‘Number Of The Beast’, ‘Run To The Hills’ and the new stuff then what’s the point?”

Rich is a teacher, one time Rhythm staff writer and experienced freelance journalist who has interviewed countless revered musicians, engineers, producers and stars for the our world-leading music making portfolio, including such titles as Rhythm, Total Guitar, Guitarist, Guitar World, and MusicRadar. His victims include such luminaries as Ice T, Mark Guilani and Jamie Oliver (the drumming one).