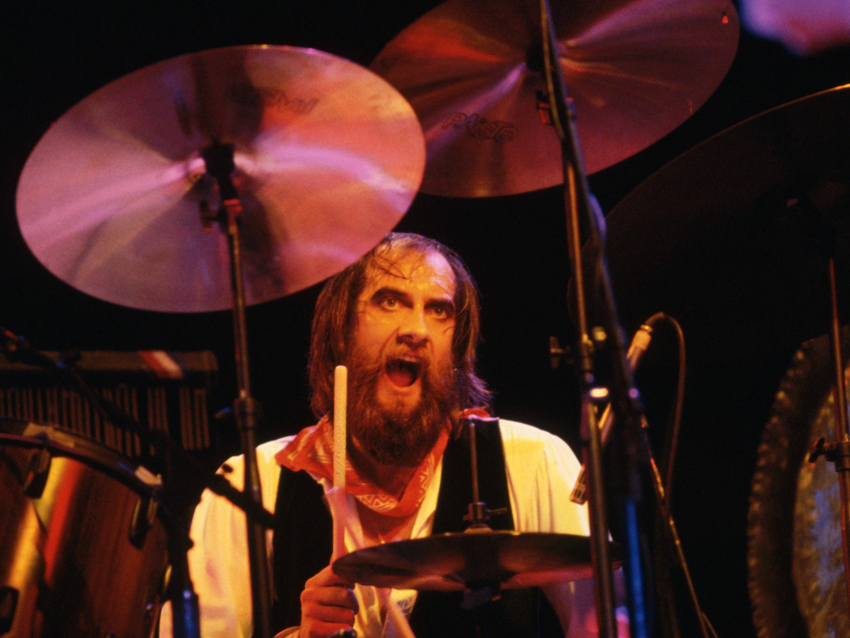

Mick Fleetwood: my 11 greatest recordings of all time

“As a percussion player, I approach my own work in a very emotional, personal way, and so I have to rely on one thing: the essence of feel," says drummer Mick Fleetwood, who since 1967 has provided the steady, deep groove for the superstar band that bears his surname. "I didn’t always understand what it was, and I used to be insecure about that, but now I truly know that I feel most comfortable when I’m emotionally involved."

To fully connect with the music he's playing, Fleetwood stresses the importance of listening, of taking the time to hear what a song needs – and, more importantly, what it doesn't. It's a quality that he says his friend and constant rhythm section partner, bassist John McVie (the "Mac" of Fleetwood Mac), shares. “We both have that," he says. "Through the years, I believe I’ve honed it down to an accidental skill."

Although he's become one of the most celebrated drummers on the planet (in 1998 he was inducted into the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame) in one of the world's top-selling bands (Fleetwood's Mac's 1977 album Rumours has moved a staggering 40 million copies), Fleetwood calls himself "a frustrated harmonic musician, except I don’t play a harmonic instrument as such – the piano, a guitar. Because of that, I have a huge interest in the people that I play with and the songs that they have written."

As for his own playing and his role in the creative process of making songs come to life, Fleetwood claims that it's a bit of a mystery. "I don’t think about what I’m going to play until I feel a personal and emotional dynamic," he says. "I’m told that what I do as a percussion player is all sort of back-to-front, where the fills are usually not in the obvious places, and it’s because I don’t really know what I’m doing. I just do it spontaneously."

Before Fleetwood Mac evolved into a Grammy Award-winning, stadium-filling behemoth, Fleetwood cut his teeth in a variety of mid-'60s British blues bands (including a brief stint in John Mayall & The Bluesbreakers, which also, at one time, counted McVie as a member). He recalls those early years as being crucial in the development of his highly nuanced style.

"Growing up playing blues, it's is all about listening and doing something that is ostensibly very simple," Fleetwood says. "But it involves great attention to dynamics. The breeding ground for me was just that, and it was a perfect match for me because I’m not ‘Joe Slicko/ Mr Paradiddle.’ I’m not horribly technically profound. I know people have said, ‘Well, that’s not true,’ but I really am happy doing something simple and getting a lot out of it.

"I was a guy who knew, through listening to blues music, when to not play – and I became an expert at it.”

On the following pages, Mick Fleetwood lists what he considers to be his 11 greatest recordings of all time, performances that he treasures for reasons both musical and personal. It's a fascinating, career-spanning mix of big hits and cult favorites, and they all share one not insignificant element: the unmistakable Fleetwood "grease."

Love That Burns (1968)

“Peter Green. Fleetwood Mac. This is probably, almost, my favorite song. It kills me. Peter kills me. He was my friend, remains a friend, and he started Fleetwood Mac with me in 1967.

“This is me in my full-on training ground. This is the essence of playing Oh Daddy, the essence of what I was able to get out of playing a form of music that allowed me, as a young chap, to express myself so thoroughly, not only vicariously through Peter – because I loved his playing so much – but when I was privileged to be playing behind somebody so talented.

“When I hear this, it’s all about a young chap, me, knowing why Peter was so overjoyed to be playing the music that he loved so much.

“This is classic slow blues. A good shuffle on a slow blues is what I will take to my grave.”

Go Your Own Way (1977)

“Lindsey walked in with a demo, in his wonderfully ordered fashion from the days when he’d just joined Fleetwood Mac, until he realized that John and I played in a certain way, which was compliant to the structures and aspirations of a songwriter.

“But really, he was very soon to learn that, because I’m dyslexically connected to drum parts – meaning that I truly don’t know how to repeat anything – my playing tends to be this funny random stuff that luckily people like. Hopefully, it has a charm to it.

“Basically, it’s my version of turning everything backwards, perfectly dyslexically, and Lindsey and I came up with something we were all happy with. It’s like the song Station Man from the Kiln House album – the fills are all backwards.

“I love playing this song. It’s one of my favorites because I get to kick the hell out of my drums, and it’s got that wonderfully primal part. It's a great ‘let loose’ stage song, in which I can revert to my old animal ways and not be quite so polite. Lindsey is a full-on rock ‘n’ roller on this song, and that I love.”

Rattlesnake Shake (1969)

“The song’s been done a million different ways by different people, Aerosmith and such. I still play it in the blues band that I have with Rick Vito. But this one, for me, is really a reminder of the freedom we had in Fleetwood Mac, which was fantastic. I learned so much from the Peter Green period of the band.

“On this song, you hear structure, yes, but you also hear me being incredibly free to break into the shuffle at the end, which was not supposed to happen, but it did and we went, ‘Oh my God, we really like that.’ I really loved that because it was my way of participating in creating the character of the song.

“It incorporated the freedom to go off on a tangent, to jam – the classic ‘Do you jam, dude?’ We learned that as players. You hear that alive and well in the double-time structure that I put in at the end, which on stage could last half an hour. It was our way of being in The Grateful Dead.”

Walk A Thin Line (1981)

“This is a Lindsey Buckingham album, written for the Tusk album. I redid it this for The Visitor, the album I recorded in Africa, and the reason I did so was because I really loved the song and wished that I’d written it. [laughs]

“I approached it with a whole ensemble of African musicians, so as a percussion player, during these recordings, I was, as we say in England, ‘like a pig in shit.’ I had the greatest time playing with these musicians on this rendition of this particular song.

“The most important thing to me was, I knew I was talking this song to Africa to reinterpret, and what you hear on the whole of The Visitor is an extension of what you hear on Walk A Thin Line.

“George Harrison was my ex-brother-in-law, so when I came back to England, he put some beautiful slide guitar on the track for me. I adore him and his music, and he is sorely missed.”

Dreams (1977)

“Dreams is a given. I think it’s the most famous song that Stevie ever wrote. The intro, I think is one of those stupidly simple things that came from the drummer who played with Al Green and The Staple Singers, so it’s from my love of what I call ‘greasy music.’ It has a real feel, and it’s lazy, behind the beat – stupidly simple but well-thought-out.

“This doesn’t work unless you attach yourself to my little speech to the band before we go on stage: ‘Keep it greasy, guys.’ So this is me keeping it greasy and letting go to form a groove that is infectious.

“The tempo of the song, I’ve been finding out, is something that really appeals to drummers, so I take that as a compliment. It’s something I took from great players who I love so much: Keep it greasy and stay in the slot. Gotta be in the slot!”

Oh Daddy (1977)

“I’m a sucker for this one because it really is a structured song, which is so appealing to me as a player. Basically, it’s me playing a slow blues with Christine.

“Sentimentally I say this, because I didn’t know it at the time, but I found out not too long afterwards, that the song was actually written about me. At that point, I was the only daddy in the ranks of Fleetwood Mac. Christine is a sister of mine and truly a great musician – and a blues player.

“This is me in a very comfortable place playing, in essence, what I would deliver in a slow blues to her song.”

You Might Need Somebody (1980)

“Turley Richards, a chap who I believe is still with us. A fantastic talent. He’s blind, a white guy but black as the ace of spades in so many ways. Very, very soulful guy.

“I always loved this song, and I love where it ended up in that slot – when I get there, I absolutely love it. I really like what I did on this and was overjoyed to work with him on this album.”

Oh Well (1969)

“It’s two minutes of madness that I love. It’s a stop-and-start song, and to this day I get the heebie-jeebies thinking that I’m going to mess it up – which is good, because that’s the child in me.

“The structures that I was able to put together make it something that is very unique. It’s become a real staple of the diet, way more so than I ever realized with our contemporaries and the best of the best – they’re absolutely fascinated with this song.

“I always jump at the chance of doing it; in fact, I got Lindsey to put it into the set for the last Fleetwood Mac tour, which was quite unusual for him to do.”

Tusk (1979)

“This is Mick Fleetwood gone AWOL. I really enjoyed working with Lindsey, who put the structure down. The song had basically been discarded during the Tusk sessions, and no one knew what to do with it. We’d made this jam song. The crazy jungle beat is very much a Mick staple diet.

“The song came back to life, on the face of it, from an asinine idea I got when I was on holiday in France. There was a brass band walking around the village, and I came back and said, ‘We need to put the USC Marching Band on this,’ and everybody thought I was crazy. Of course, we did it, and it’s become one of the classic Fleetwood Mac songs in concert.

“I have a ball playing it because it’s really rudimental, with simple stuff that’s very effective. On record, the drum break in the middle is a huge cacophony of looped tapes and madness, but on stage of course it’s played. If you think about it, it has memories of one of the sections in Oh Well.

“I’m playing floor toms, and I overdubbed a lot of American Indian wood tribal drums. It’s a whole hodgepodge of Kleenex boxes, drums, weird stuff, slapping of lamp chops and things. I got a big leg of lamb in there somewhere – I’m hitting it with a spatula.” [laughs]

Werewolves Of London (1978)

“Most of the tracks I’ve chosen are me playing with John McVie, but this one is an example of the two of us being hired as a rhythm section. We approach our music like that: We’re old school. We’re not interested in showing off; we’re interested in being compliant and supporting the music that’s there. This was Warren Zevon picking up the phone and saying, ‘I need the section on this one.’

“Being in the pocket. It’s the one thing I’ve lucked into, and it’s the one thing, by the people I’ve been privileged to have played with – mostly, in truth, Peter Green and of course John – that I got out of it. It's survived me.

“It’s the classic Mac rhythm section laying down a bit of grease for Warren Zevon, who is sorely missed.”

You Weren't In Love (1981)

“A great song. I took it to Africa, and more than the playing, it was all about the sadness of the song, which is so beautifully correct harmonically.

“However, if you listen to the words, there’s such great sadness there, too. At that point, in truth, I identified with them. I wasn’t a happy camper back then. Being the blues hound that I was, I remember licking my wounds and playing that song in Africa. The few times I’ve been able to regurgitate the song on stage, dare I say there’s been a wet eye in the Fleetwood skull.”

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.

“Tonight is for Clem and it’s for friendship. An amazing man and a friend of the lads”: Sex Pistols dedicate Sydney show to Clem Burke

“Almost a lifetime ago, a few Burnage lads got together and created something special. Something that time can’t out date”: Original Oasis drummer Tony McCarroll pens a wistful message out to his old bandmates

“Tonight is for Clem and it’s for friendship. An amazing man and a friend of the lads”: Sex Pistols dedicate Sydney show to Clem Burke

“Almost a lifetime ago, a few Burnage lads got together and created something special. Something that time can’t out date”: Original Oasis drummer Tony McCarroll pens a wistful message out to his old bandmates