John Densmore talks drumming, classic tracks and his book The Doors Unhinged

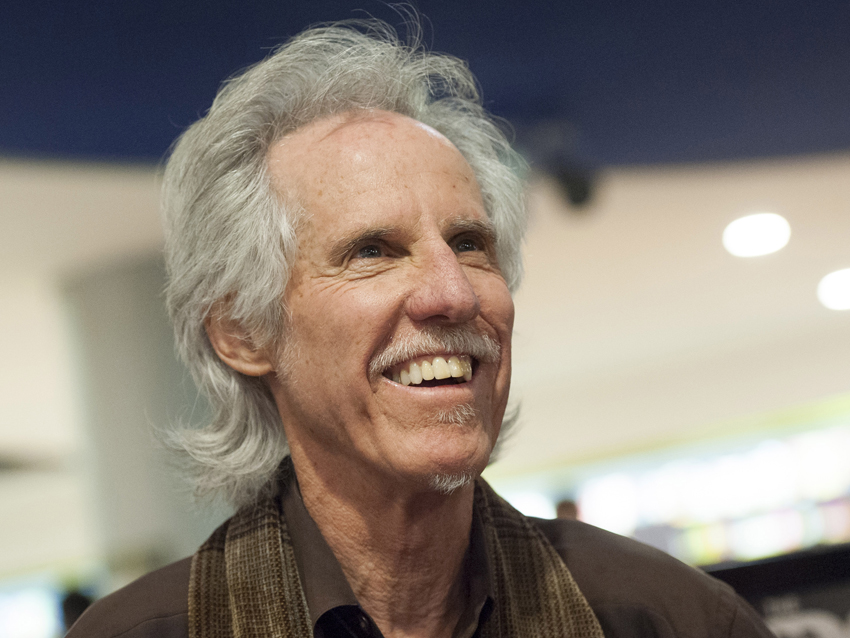

A year after releasing his second memoir, The Doors Unhinged, drummer John Densmore is still on the book store circuit signing copies of his engrossing and oftentimes harrowing account of the battle he waged for The Doors name and the lawsuit he brought against his two former band mates, keyboardist Ray Manzarek and guitarist Robby Krieger.

The subsequent trial turned deeply personal at times (at one point, opposing counsel, in an attempt at character assassination, made a far-flung claim that Densmore sided with Al Qaeda), threatening to forever upend the harmony that existed for decades amongst the surviving Doors members. “Suing my musical brothers was definitely not fun," Densmore says. "They thought I was crazy, but I had to do it. And it was very difficult; it was like I was being crucified, pulled in one direction and another."

The book differs from Densmore’s first memoir, Rides On The Storm: My Life With Jim Morrison And The Doors, a first-rate chronicle of the group's history and drummer's difficult relationship with the hard-living "lizard king," but it’s no less gripping, recounting the courtroom proceedings with Woodward and Bernstein-esque detail and examining how Densmore's relationship with the surviving Doors first soured after he refused to OK a lucrative Cadillac deal and deteriorated even further after Manzarek and Krieger hit the road as the Doors of the 21st Century.

"For me, at first the lawsuit was like, ‘Well, I shouldn’t do this – they’re my musical brothers,'" Densmore recalls. "But then I thought, ‘No, Jim would have wanted it this way. I should do it.’ But it was hard – really hard.”

Densmore sat down with MusicRadar to talk about the trial, mending fences with Krieger and the late Manzarek, classic Doors tracks and the some of the particulars of his unique drumming style.

(John Densmore's The Doors Unhinged is available on Amazon, Amazon Kindle, Kobo and Smashwords.)

The trial got so intense and personal. At any point, did you say to yourself, “This is too crazy. It’s too much. I’m just going to end it”?

“I said it a lot, sure. Not at any specific point – in the middle, when it got really intense. You know, I was risking my finances. That was pretty scary.”

And finances you didn’t even have.

“Well, I had finances, but I could’ve lost it all.”

On Ray Manzarek

Were things between you, Ray and Robby acrimonious before the Cadillac ad and before they toured using The Doors name?

“No. No, not really.”

You prevailed in court, and you did eventually manage to bury the hatchet with Ray and Robby.

“Yeah. Thank God.”

Who made the first move?

“Before the book was published, I sent the last chapter with a note to Ray and Robby saying, ‘This might be a hard pill, this book, but I wanted to make sure you got to this. This is where I say I love you guys. How could I not? We’re musical brothers.’ Then when I heard that Ray was getting really sick, I called him… Thank God we had that closing phone call. When he passed, I said to Robby, ‘Let’s try to honor Ray with a concert or something,’ which we’re still struggling with.”

If Ray hadn’t become ill, do you think the three of you might have performed again?

“Yeah, but I don’t know in what way. Maybe we could have done some jazz. I just don’t want to fall into the trap of replacing Jim. He’s irreplaceable. When we did that VH1 Storytellers, it was six singers, and I liked that. I said to Robby, ‘Hey, let’s go on the road with six singers. Or four. That way we wouldn’t fall into the trap.”

In his testimony during the trial, Ray changed the account of your last conversation with Jim. [John laughs] He said that you told Jim how you wanted him to come back and go on tour. Was that ever really a hope within the band?

“No, no… In his book, he said that I called Jim begging him to come back, and I said, ‘Ray, c’mon, that’s ludicrous.’ And then he changed it in the paperback or something, saying that Jim called me. I mean, Ray wasn’t in my house eavesdropping on the phone call. How would he know what the fuck was said? [Laughs] Excuse me, Ray.

“I mean, may the great Ray rest in peace. I’ve been thinking about how great and unique he was to the band. To split his brain and be the bass player for the band with his left hand – it’s just miraculous.”

Drumming influences

You’ve written two excellent and very successful memoirs. Do you have any plans for a third?

“Well, I’ve discovered that I really like writing, and I feel that I’m good at it. I’m mulling around in my head some more stuff. I’ve got several ideas. No more memoirs, though.” [Laughs]

You were saying how unique Ray was, but you're pretty unique yourself. To my ears, you and Ringo Starr are two drummers that other players can never quite copy.

“Maybe that has some to do with what Ringo said when they invented drum machines: ‘I’m the fucking drum machine!’ [Laughs]

Now, Ringo is left-handed but he plays righty –

“Oh, well, I’m the same. I didn’t know he was left-handed. Cool – if I ever see him again, I’m going to have to run that by him.”

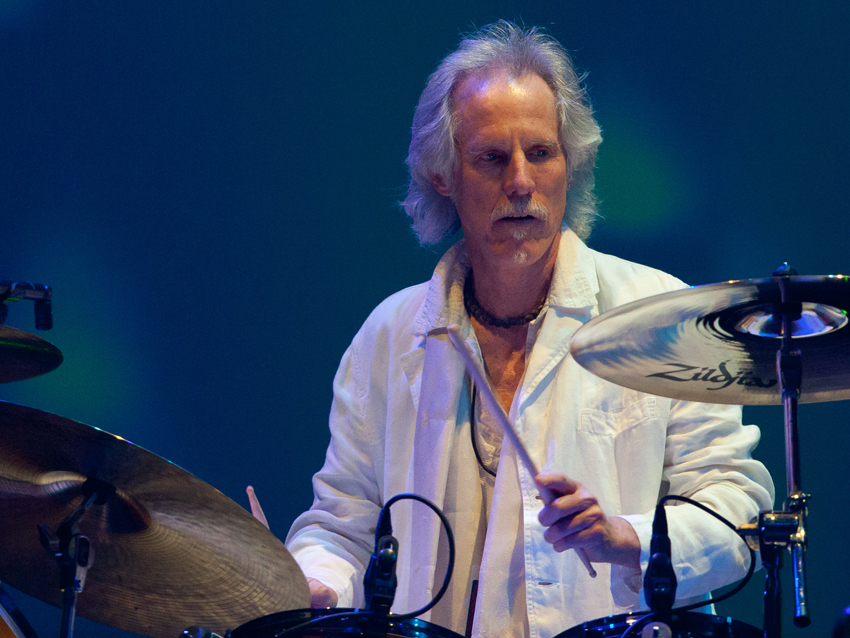

You’ve talked about being influenced by Elvin Jones, but who else were some of your early influences? You do play with a traditional grip.

“Art Blakey comes to mind immediately. I sat right next to his hi-hat and stared into his kit at Shelly’s Manhole. I certainly copped and worked on press rolls – he was a master of that. I threw a couple of them in, I don’t know where… Wild Child and a couple of other songs. When I do a press roll, I use the traditional grip. Sometimes I flip it around; for a louder crack on the two and four, I use the new grip.”

There’s a nimbleness to your style, and it probably comes from jazz. You’re not a pounder.

“Yeah, that’s right. My hands are good, but my feet – God, when Billy Cobham came in, practically doing a roll on the bass drum with the right foot alone, my God, I just died! [Laughs] I’m still trying to get that technique, the way you sort of play with the ball of your foot and bounce it – I can kind of do it, but not like a lot of drummers. But my hands have always been good. I think that’s drum rudiments.”

Light My Fire

Do you have any quirks as a drummer? Drum height or placement, tuning…

“You know, another jazz drummer, Ed Thigpen, who played with Oscar Peterson way back – it was the first time I ever heard rivets in a cymbal. And then I heard that Chico Hamilton had them too, and I went, ‘Oh, that’s it. I’m taking that for my sound.’ And it worked well on Riders On The Storm, so that’s one thing.

“I have the ride cymbal kind of low, so I can ride on it. I look at some guys – there’s some incredibly technical heavy metal drummers, but it’s bizarre how a lot of them have their cymbals up really high and almost perpendicular. You crash ‘em, and that’s all you can do – all you do is crash. I like the subtleties. Play the bell.”

Improvisation was always a hallmark of The Doors' music but also in a lot of the other projects you’ve been involved with. Could you have thrived in something that wasn’t improvisational?

“That’s an interesting question. Maybe not – I don’t know. You have to do your homework, and of course, it’s good to have form. I don’t like totally free jazz, unless it’s done by somebody like Coltrane, who did bebop and cool jazz, so he was allowed to go out there. I love trying to be in the moment and playing off of whatever’s going on. That’s improvisation, really. Keeping the pulse – that’s the main job – but I like to spin off of the moment.”

Speaking of improvisation, did you ever play Light My Fire the same way twice?

“No. That song was always a lot of fun to play live because of the long solos – it was new every night. There were always little nuances here and there, just like jazz.”

I love the album The Soft Parade, but at the time of its release, the critics were less than kind. Who spearheaded the direction of the album – the strings, the horns?

“When Ray and I first met, we talked about jazz, and we wanted to try strings and horns – before we even recorded the first album. So then when Sgt. Pepper came out, we said, ‘OK, let’s do this.’ We had a lot of fun doing it. The critics… they fall in love with a sound, and then they get pissed off. But we wanted to try that experimentation from the beginning, and we thought, ‘Someday, later, we’ll expand it.’

“We wouldn’t have gotten back to Morrison Hotel and LA Woman if we hadn’t gone way out there and tried a big orchestra thing. And then we thought, ‘All right, that was great fun… ‘ I mean, Touch Me went to number one – the audience got it. The critics got ornery. Then we wanted to get back to our roots, the blues, and LA Woman was the ultimate, where we denied technology and used eight-track instead of 16, which was Morrison Hotel. We did it in our rehearsal room, really trying to get back to the garage, where it all started.”

Performing without a bassist

The song The Soft Parade is a mini epic. How was it written?

“In sections. Long, epic things like The End and When The Music’s Over, they evolve over time. Jim always had these lyrics, and we would spring off that.”

When Paul Rothchild [producer of all The Doors' albums with the exception of LA Woman] criticized Riders On The Storm and called it “cocktail lounge music,” did those words sting? Or did you just think, “Well, he’s wrong”?

“No, it kind of hurt, because he had taught us how to make records. He was brilliant. But he got dictatorial and made us do too many takes in the middle there. Unknown Soldier, Waiting For The Sun – it was ridiculous. Ridiculous. And I really felt that there were a few takes in the can other than the master they he chose that were better because we weren’t so tired. We were just playing it over and over and wringing out the vitality.

“Still, he was a teacher and a mentor, so it hurt. But later, what happened was, we were freed and we were thrilled to take the reins – it was time to do it. And Paul was fed up with Jim’s alcoholism. It was pretty hard during Soft Parade. They had to do a lot of takes on the vocals and patch them together. But producing [LA Woman] with Bruce Botnick empowered us, and Jim kind of shored up and wasn’t that loaded.”

Live, the band performed without a bass player. Now, drummers usually like to lock in with the bassist. What did you do live? Who would you look at?

“I was watching Jim all the time. But I was the pulse without a bass player. Yeah, usually, bass players and drummers are together. I had a double job: I had to hold the tempo down ‘cause it was just me and Ray’s left hand. But he would get excited when he played an organ solo, and then he’d speed up. So I had to really hold back.

“Without the bass, there was more air, and that let me play around with Jim more – spur him on, have conversations. You know, like in When The Music’s Over – ‘What have they done to the earth?’ ‘Brrrrrrr!’ That kind of stuff.”

Dark side to fame

In the studio, you used bassists quite a bit. Would you track in a conventional way?

“On the first album, Larry Knechtel – late, great studio bass player – just overdubbed Ray’s basslines. We didn’t have Moog synthesizers, and the keyboard didn’t have the punch we needed. We needed a string, a bass string. Then later we started using bass players, and they’d add their own stuff. Like Jerry Scheff, who was on LA Woman, he twisted the bassline on that song. It was a lick that Ray played on a keyboard, but he couldn’t finger it. So bass players added stuff. Harvey Brooks – oh, what a great bass player. That was a lot of fun.”

What was the band’s relationship with Elektra like? Were label execs ever bugging you for “the next Light My Fire”?

“No, they were totally supportive. They let us do our thing, and then they’d choose a single. They’d lobby – I mean, they talked with us – but it would be their decision.”

How was your onstage equipment back then? Did things ever break down?

“It was… small at the beginning, and then it got really big. We had it all pretty together.”

So you could hear yourselves on stage? You didn’t play to screaming girls like The Beatles did, but your audiences were pretty raucous – sometimes there were riots!

“Well, yeah, but then when we played The End, everybody would get really quiet and then leave. [Laughs] Which was great – they were taking it all inside instead of dispersing it with applause.”

A lot of times, people tend to focus on the downsides to fame. What was great about being a pop star in the ‘60s?

“It was both great and hard, because Jim had a problem. Your buddy’s destroying himself, and you can’t seem to do anything about it. There weren’t substance abuse clinics, and so we didn’t really know what was going on or why it was happening. We were making great music, but it was difficult.”

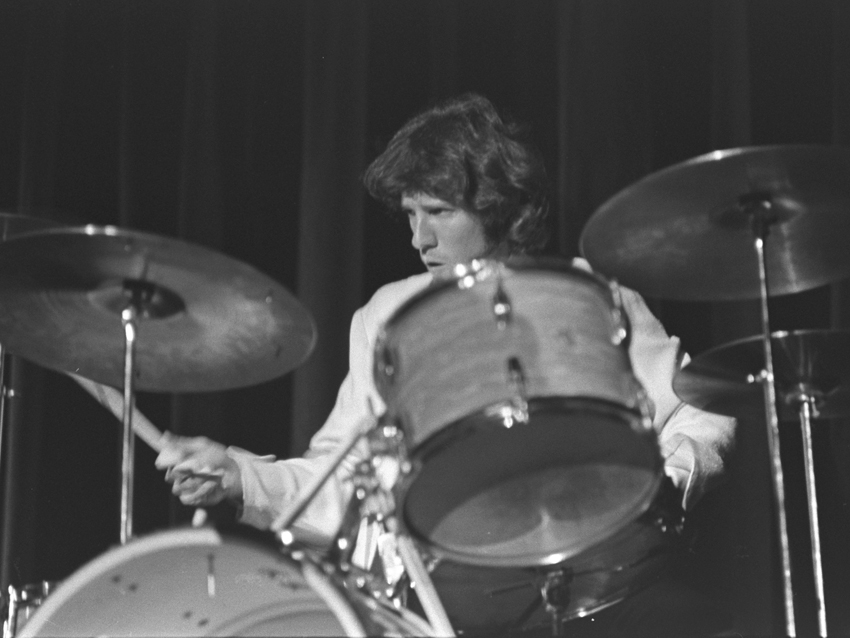

From Gretsch to Ludwig

Guitarists tend to lust over certain models – vintage Les Pauls and Strats and so on. Were you ever that way when it came to drum kits?

“No, not really. I liked a small kit – I felt as though you could do everything with that. When I saw Mahavishu Orchestra – we were on a bill with them, after Jim died – and they pushed out 30 drums or whatever Billy Cobham had. I thought it was a joke, that he would never hit them all – but he did! [Laughs] A mind-blower. Everybody should have what’s right for them.”

What brought about your move from Gretsch to Ludwig in late ’67?

“I liked the sound of Ludwig. I have a Ludwig piccolo chrome snare and a regular-sized one, and I just like them.”

For the most part, you stuck to a four-piece configuration, but in 1970 you added some small tom-toms.

“Yeah, I started fooling around with more tom-toms. It wasn’t really my thing, though. I only had the two, and then I had a floor tom.”

You weren’t seduced intro trying double bass drums like so many other drummers.

“No, I wasn’t. If I couldn’t do with my right foot what Billy Cobham could do, then I didn’t deserve another bass drum.”

Billy Cobham made quite an impression on you.

“Well, I’m just thinking of him as the ‘foot man.’”

The Doors made it in fairly short order. You didn’t have to slog it out for years and years like some bands –

“Yeah, but each of us had rehearsed our particular instrument, and Jim had read every book on the planet for years before that.”

How long would you have stuck it out with The Doors if you didn’t get signed right away?

“That’s an interesting question. The Doors were dedicated. We were a band a brothers, the four of us. We were gonna keep at it.

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.